Bridging Knowledge and Action: The Community Hydrology Approach

The Rural Futures team conducting the community hydrologist programme in Raichur.

‘Learning by doing’ is a teaching method that emphasises hands-on learning, like a pottery class where you learn to shape clay by using a wheel. While this practical approach has many benefits, it raises important questions: Which learning tools are the most effective? How can we better translate knowledge into action? These questions came to mind as we wrapped up the first of four community hydrology training programmes in Raichur, Karnataka.

WELL Labs is conducting the community hydrologist programme to engage local stakeholders and tackle complex challenges of rural and urban water resilience.

The goal is to build long-term capacity within the community, equip youth with employable skills, and enable effective water management at the grassroots level through water user cooperative societies (WUCS).

By involving farmers in citizen science activities, such as collecting monthly data on groundwater levels, rainfall, and cropping patterns, the programme fosters collaboration to create a regional water balance. This data-driven approach supports informed decision-making on water use.

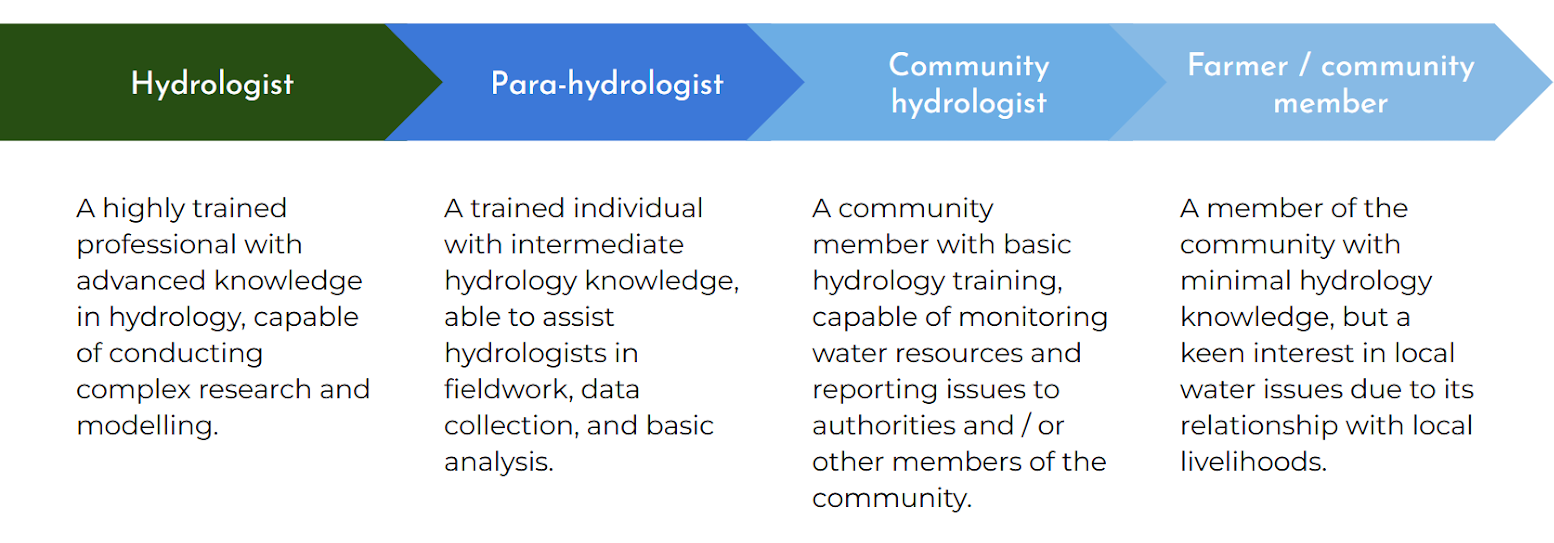

The programme also addresses a critical gap between the scientific study of hydrology and its practical application. Various individuals can fill this gap — from professional hydrologists to para-hydrologists and community members who may have minimal formal knowledge of hydrology, but possess a deep interest in water issues due to their impact on livelihoods.

Over time, we envision the skills and expertise of community hydrologists evolving into a sustainable service model. Under this model, they will offer paid services to gram panchayats, farmer producer organisations, and local administrations to support better decision-making on water use, optimal irrigation timing, and water resources’ just and equitable allocation.

The community hydrology programme is part of Climate Adaptation and Resilience in Tropical Drylands (CLARITY), a research project to build equitable, sustainable, and climate-resilient development pathways in tropical drylands.

A key component of this project is setting up Transformation Labs (T-labs) — collaborative spaces to create knowledge and solutions for water and agricultural challenges. In India’s tropical drylands, characterised by low rainfall and semi-arid conditions, communities rely heavily on groundwater for their livelihoods. However, without proper management, groundwater resources face depletion, unequal access, and unsustainable use. The community hydrology programme seeks to address this challenge.

Reflections on the First Community Hydrology Training Sessions

The first session, conducted from November 13-15, saw enthusiastic participation from 35 farmers in Devadurga taluk in Karnataka’s Raichur district. It blended theoretical and practical sessions to ensure participants could connect concepts to real-world applications.

Key Successes

- Strength in collaboration: Partnering with Prarambha, a local NGO, facilitated smoother ground operations, community mobilisation, and logistics.

- Clear direction: A selection process and orientation session helped farmers understand the programme’s objectives and benefits and fostered strong commitment.

- Hands-on learning: Practical sessions sustained interest and reinforced theoretical concepts. The training included a well inventory assignment, where farmers were grouped into 14 teams to survey 80 wells across two villages — one in a canal command region and one in a rainfed region.

Lessons for Improvement

While the programme was well-received, there were areas for improvement:

- Contextualising theory: Theoretical concepts could have been more effectively linked to local challenges. For instance, showing rock specimens would have improved their understanding of geological concepts.

- Language accessibility: Simplifying technical jargon and using the local language is essential. While we had translators, the process of translating the sessions from English and Hindi to Kannada and participants’ questions in Kannada to English was time-intensive.

- Prioritising content: Clearly distinguishing between ‘critical knowledge’ (e.g., measuring well depth in units that farmers are comfortable with) and ‘good-to-know’ information (e.g., unit conversions) could optimise learning outcomes.

The programme reaffirms that learning is most valuable when it addresses real-world needs.

Farmers showed a preference for relatable narratives over technical details. They were less interested in theoretical topics (for example, aquifer types) and more focused on actionable knowledge: how to manage water effectively, improve crop yields, and adapt to climate variability. Thus, training should empower them to make informed decisions about water management and crop planning, transforming learning into meaningful, livelihood-enhancing actions.

We are using participant feedback from the first session to improve the learning experience in upcoming sessions.

To maintain engagement and ensure focused content delivery, we shall limit presentations to 15 minutes each. The sessions will primarily be in Kannada to overcome language barriers and encourage greater participation and discussion.

We shall prioritise hands-on learning, enabling participants to engage directly with the material and apply their knowledge in practical scenarios. Extended live demonstrations in the field will provide real-world context, allowing them to observe techniques in action and ask questions on the spot. By emphasising practical learning, we seek to equip participants with the skills and confidence to effectively apply water management concepts in their daily lives.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by UK aid from the UK government and by the International Development Research Centre, Ottawa, Canada as part of the Climate Adaptation and Resilience (CLARE) research programme. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of the UK government, IDRC or its Board of Governors.

About CLARE

CLARE is a UK-Canada framework research programme on Climate Adaptation and Resilience, aiming to enable socially inclusive and sustainable action to build resilience to climate change and natural hazards. CLARE is an initiative jointly designed and run by the UK Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office and Canada’s International Development Research Centre. CLARE is primarily funded by UK aid from the UK government, along with the International Development Research Centre, Canada.

About CLARITY

Climate Adaptation and Resilience in Tropical Drylands (CLARITY), a research project under CLARE, is building equitable, sustainable, and climate-resilient development pathways in tropical drylands. This Global South-led project will result in the creation of long-term assets (data and tools) and capacities to achieve transformational change.

Authored by Navitha Varsha and Arjuna Srinidhi

Edited by Ananya Revanna and Saad Ahmed

Published by Ananya Revanna

If you would like to collaborate, write to us. We would love to hear from you.

Follow us and stay updated about our work: