Can Farmers Make More Money While Using Less Water?

India’s farmers are stuck between a rock and a hard place. On the one hand, the country is facing a groundwater crisis with about a quarter of India’s blocks labelled ‘overexploited’ or ‘critical’. On the other hand, farmer incomes are stagnating or falling. For them to make more money, they need more water to cultivate crops like paddy or wheat. But they don’t have the money to dig new or deeper borewells or arrange for tankers to meet the high water demand of these crops.

This dilemma is only going to sharpen over time, which is why it is critical that we work towards pathways that enable farmers to make choices that improve their income while simultaneously allowing them to cut down on their demand for water.

Read: Why We Need Data Stories and Digital Tools To Achieve Rural Water Security

This is not a new problem and the solution is logical. And yet why is it so hard to make a sustainable transition? What does this mean for the agriculture sector, which is complex and vulnerable to multiple intersecting risks from adverse policies to climate change?

There is no standard definition for sustainable agricultural transitions

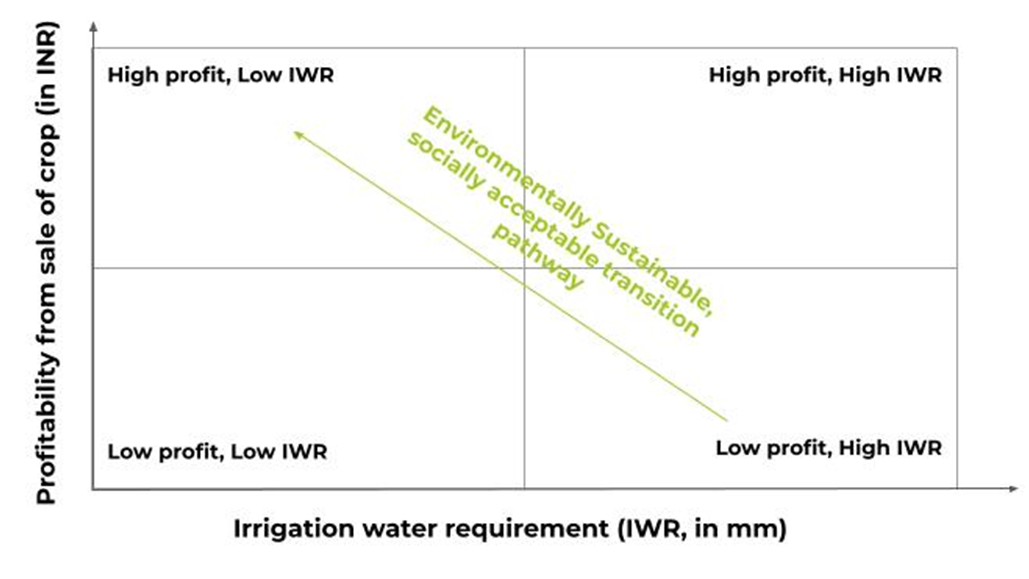

We are approaching sustainable transitions through a water-for-agriculture lens — a sustainable transition is one where a farmer reduces irrigation water use while increasing their income. Sustainability is thus evaluated from both hydrological and economic perspectives.

In this context, a sustainable transition that is also socially acceptable would be one that involves a farmer transitioning from a low-profit, high-water using crop to a high-profit, low-water using crop, like moving from paddy to a fruit crop like mango.

Irrigation profitability trade-off

The existence of sustainability transitions are promising, but they may not always materialise because many factors including risk appetite, technical know-how, social networks and culture influence farmers’ choice of crops.

One of the most important considerations is that farmers are not making decisions on the basis on maximising profit alone. They also seek to minimise risk.

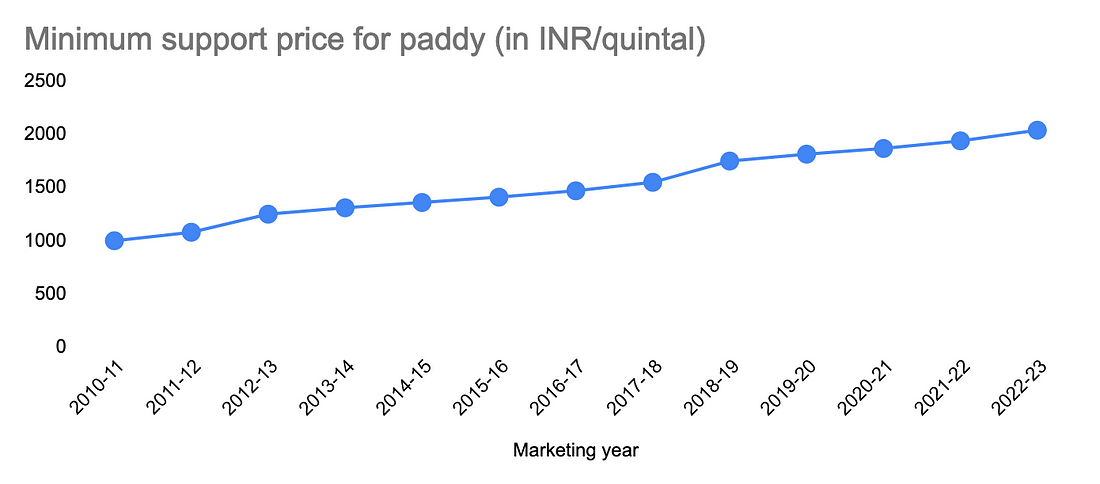

Take for example a farmer in Punjab, a state where the government guarantees a Minimum Support Price for a list of crops including water-intensive ones like paddy. If this farmer is risk averse and has access to water, there is a higher probability that they would opt to cultivate paddy over horticultural crops that may consume less water but lack the MSP safety net.

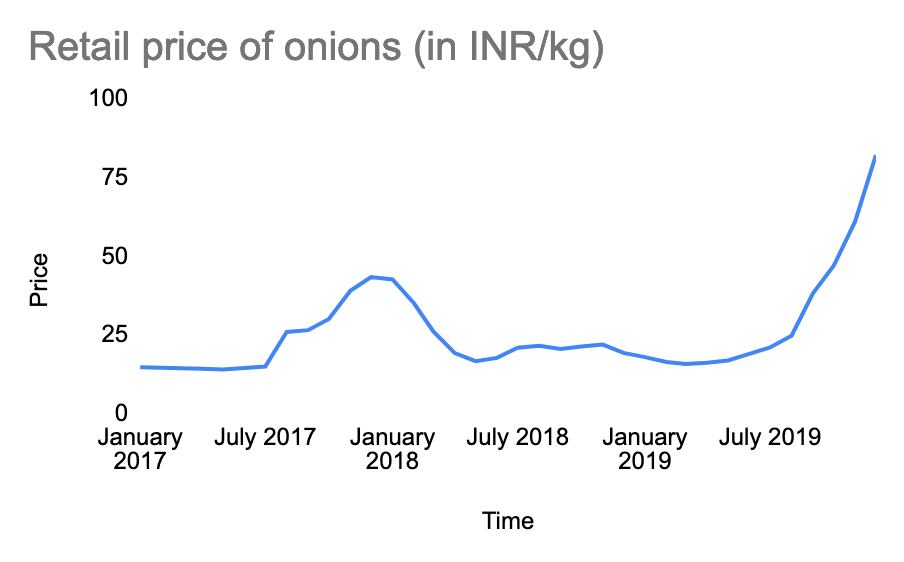

Market price of onions over three years (2017–2019)

For non-MSP crops like onions, it is clear that prices fluctuate wildly over short periods of time. These prices are often determined by the total amount of produce in the market. Excess supply causes the price of onions to plummet, and a dip in supply results in increased prices. This is true for most horticultural crops that don’t have an MSP. But these horticultural crops often have lower irrigation water requirements compared to paddy.

There are ‘lock-ins’ that prevent sustainable agricultural transitions

Therefore, it is difficult to balance the economic aspirations of farmers with environmental concerns. Current agricultural and energy policies, such as MSPs, are geared towards the production of some crops over others and have thus resulted in unintended consequences, like depleting groundwater levels.

This is what we call a ‘lock-in’ in the agricultural sector. When generations of farmers follow certain patterns of behaviour in terms of crop choices or cultivation practices, it is hard for them to break out of known routines. There is little incentive for them to do so when the policies in place favour current water-intensive practices.

It is critical to understand ‘lock-ins’ because this is a key factor that dictates how sustainable interventions can be introduced successfully, without hampering the needs and aspirations of farmers.

One such intervention could be solar irrigation, a concept that is gaining popularity in India. How would farmers behave if they were given the option to use solar-powered irrigation? Would it be status quo? Would they end up pumping more water? Or would they sell excess energy back to the grid and earn an income from it? Most importantly, would this added source of income allow them to slowly shift to less water-intensive crops?

We conducted modelling exercises to understand changes in farmer behaviour

There are no clear answers to these questions because of how diverse the ecology and socio-political contexts are in India. A solution that may be a boon for farmers in one part of the country, could be a curse in another. This is why it is important to conduct agent-based modelling (ABM) exercises in different scenarios (or states) to, as accurately as possible, understand changes in farmer behaviour.

As part of a project funded by the International Water Management Institute (IWMI), we conducted ABM to understand changes that are likely to result from the introduction of solar irrigation in six districts — Bathinda in Punjab, West Champaran in Bihar, Bengaluru Rural in Karnataka, Nadia in West Bengal, and Anand and Botad districts in Bihar.

In most of our case studies, we found the existence of strong lock-ins that prevent farmers from drastically shifting away from the status quo cultivation practices.

We will soon publish the full report documenting our methodology and the results of our modelling exercises and stakeholder consultations on how solar irrigation is likely to fare in different circumstances.

Credits

This work was conducted by the authors when they were with the Centre for Social and Environmental Innovation at the Ashoka Trust for Research in Ecology and the Environment (CSEI-ATREE). The work is now being taken forward by WELL Labs in collaboration with ATREE.

Edited by Kaavya Kumar

If you would like to collaborate with us outside of this project, write to us. We would love to hear from you.

Follow us and stay updated about our work: