Co-Creating Solutions with Communities | Insights from the Futures Research Programme

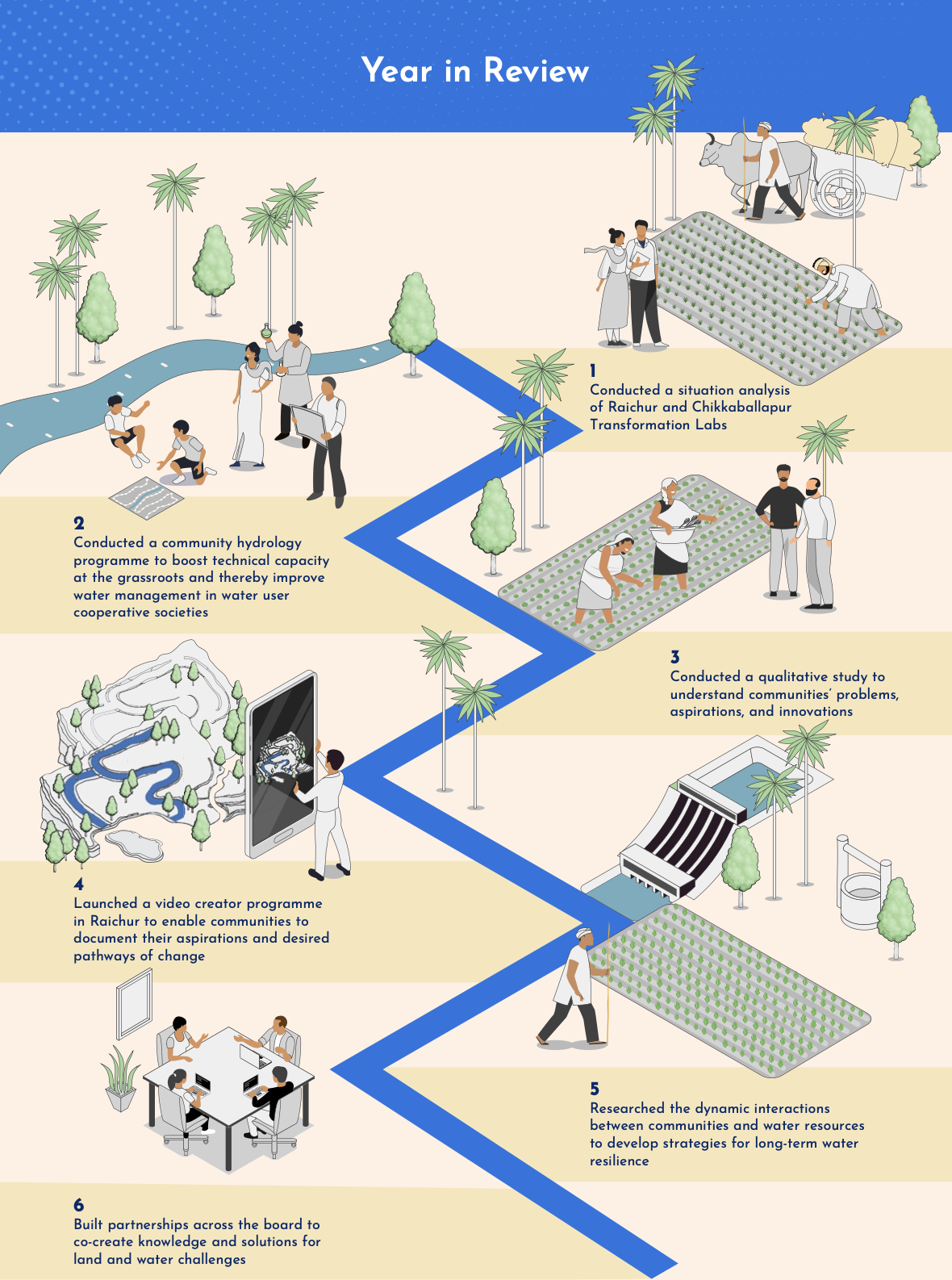

The Futures Research programme works in ‘Transformation Labs’ (T-Labs)—collaborative spaces where communities co-develop and test sustainable, equitable solutions. The programme has established T-Labs in Chikkaballapur and Raichur districts, under the Climate Adaptation and Resilience in Tropical Drylands (CLARITY) project. Over the past year, we:

- Conducted a situation analysis of Raichur and Chikkaballapur T-Labs.

- Conducted a community hydrology programme to boost technical capacity at the grassroots.

- Conducted a qualitative study to understand communities’ problems, aspirations, and innovations.

- Launched a video creator programme in Raichur to enable communities to document their aspirations and desired pathways of change.

- Researched the dynamic interactions between communities and water resources to develop strategies for long-term water resilience.

We collaborated with the Advanced Centre for Integrated Water Resources Management, British Geological Survey, BORDA, Cardiff University, Friends of Lakes, Institute of Development Studies, Prarambha, TIDE, University College London, University of Agricultural Sciences Raichur, and University of Sussex, among other organisations for these initiatives.

Illustration by Sarayu Neelakantan

Our work with our partners shaped the following insights:

1. Navigating futures research terminology—visioning, scenarios, interventions, pathways, etc.—requires conceptual clarity, but also the openness to accept plural definitions.

As we work with different teams in WELL Labs and external stakeholders, there have been discussions about CLARITY-specific jargon. These opened the door to fundamental questions about the project:

- If the Transformation Labs are a collaborative endeavour of the community, researchers, and practitioners, who takes ownership of outputs and outcomes?

- Who facilitates activities?

- How should different stakeholders collaborate?

- How do we foster coherence among contradictory visions and goals?

This spurred us to develop a common understanding of project-related jargon and goals. However, in the collaborative spirit of the project, we must also remain open to nuancing this shared understanding with diverse perspectives.

2. Farming communities excel at learning and applying complex scientific concepts, such as evapotranspiration, soil moisture, and flow control—provided the learning is grounded in their lived experiences.

The participants in the community hydrology programme preferred relatable narratives over technical details. They were less interested in theoretical topics (for example, rock types and geological eras) and more focused on actionable knowledge: how to manage water effectively, improve crop yields, and adapt to climate variability. Thus, aligning the community hydrology workshops with immediate local concerns like canal water reliability and land degradation made the pedagogy more engaging.

Field and demonstration-based learning formats were also effective in helping participants understand water management concepts. For example, a physical 3D aquifer model we built was useful to:

- Communicate the concepts of confined and unconfined aquifers.

- Link these concepts to the depths of dug wells and borewells.

- Discuss subjects like infiltration, recharge, and the sustainable use of groundwater.

Also Read | Situation Analysis: Raichur Transformation Lab

Aligning the community hydrology workshops with immediate local concerns makes the pedagogy more engaging

3. Working on sociohydrological systems can be complicated as environmental and social considerations might not neatly overlap. Transdisciplinary approaches can help overcome this challenge.

Natural boundaries such as the ridge line of a catchment area do not necessarily coincide with the political boundaries of a village or district. Thus, finalising the boundary conditions and boundaries of the Transformation Labs required several rounds of consultations between hydrologists, engineers, social scientists, and development practitioners.

In the case of Raichur, some of the considerations that helped define the boundary were:

- The pros and cons of focusing on the command area of Narayanpur Right Bank Canal vis-a-vis the surrounding regions that do not receive canal water.

- Unequal water availability for farmers in the head-end and tail-end areas of the canal.

- Topography of the upper Krishna basin.

Thus, multidisciplinary approaches helped ensure that the Transformation Lab is representative of the region it is situated in.

4. Futures research requires a fine balance between aspirations, imagination, and science.

While desired future scenarios must be grounded in communities’ needs and aspirations, we must also be able to collectively imagine a range of possibilities beyond them. This imaginative exercise becomes particularly important when working towards systematic transformations over long timespans, such as 2–3 decades. However, most civil society and government interventions have a shorter horizon, such as 3, 5, or 10 years.

Asking “What kind of future is possible?” requires us to look beyond immediate problems, while still solving for them in the short term. We need to cultivate imagination that is not constrained by the present and an openness to plural perspectives to conjure a range of possible futures. Thus, the research design for future pathways needs to be methodologically robust as well as creative and fluid to account for future unknowns.

Acknowledgments

Authors Arjuna Srinidhi, Dina Zaman, Susan Varughese

Editor Syed Saad Ahmed

Published by Nanditha Gogate

Follow us to stay updated about our work.