Grey to Green: Mapping Bengaluru’s Apartments and Parks

The Winfield Layout Park in Yelahanka was mostly parched and wilting when we first visited in December last year. It did not have access to a steady supply of water. During the dry months, this park had to rely on the goodwill of a resident across the road, who has a borewell in his premises. He was willing to provide water for an hour every day that was barely enough to revive the park flora.

This is not sustainable. Not every languishing green space or park in a metropolis as large as Bengaluru can rely on, one, individuals who are willing to expend the time and resources to nurture the park and, two, ever-deepening borewells that are sucking aquifers dry. In Bengaluru alone, the amount of water required to irrigate urban green spaces is around 35 million litres of water every day, and currently, it is freshwater that is being used. This is far from ideal at a time of worsening water scarcity.

So, why don’t we use treated wastewater instead?

Analysis by CSEI’s Cities & Towns Initiative found that the estimates for total available treated wastewater in Bengaluru vary from about 20 billion to over 200 billion litres of water a year.

If we effectively utilise this to green public spaces, we can potentially consume about 13 billion litres of this wasted resource a year.

This is the rationale driving the ‘Grey to Green’ campaign; CSEI is acting as a knowledge partner for this project launched by the Karnataka State Pollution Control Board.

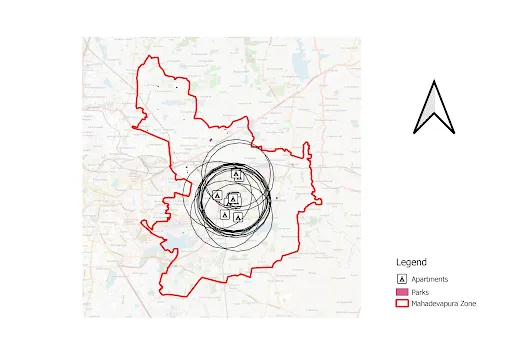

This project aims to help apartments channel their excess treated wastewater for greening public parks and medians. To understand the landscape properly and to link sources of wastewater (apartments) and sinks (nearby parks, medians), we needed to carry out a thorough mapping exercise. We also wanted to assess the kind of storage infrastructure in these parks.

Verifying datasets with groundwork

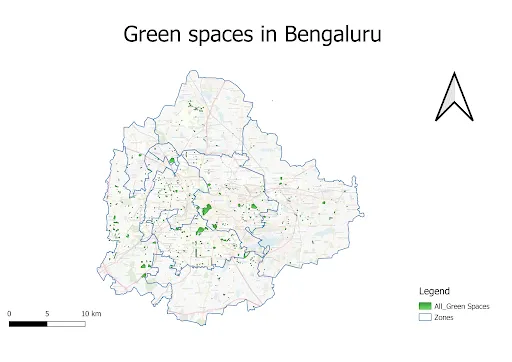

For the first stage of this project, we focused on identifying parks in Yelahanka and Mahadevapura zones (there are totally eight administrative zones under the BBMP). As with data about lakes in Bengaluru, there are inconsistencies in government databases on parks as well, with different departments using different lists. For example, the BBMP has 139 parks in Yelahanka and Mahadevapura zones, while the list provided to us had 120 parks. Most of these parks had vague official names and improper locations that even the park keepers couldn’t identify on paper. The first task on our hands was to verify the existence of these parks ourselves.

We tagged along with a BBMP horticulture department staff who works in these zones to help guide our round of surveys. Then we used an ODK form — an open access digital tool for data collection — to record all the relevant information we needed including the park name, location, area in sq. mts., current source of water (borewell or tankers arranged by the Bangalore Water Supply and Sewerage Board), watering duration and frequency, the capacity and type of storage, if available.

We also took photographs and recorded other observations on the state of maintenance, level of green cover and the kind of infrastructure in place other than storage tanks, such as pumps and sprinklers.

So far, we have surveyed 72 parks in Yelahanka and 35 parks in Mahadevapura. The next step was to identify parks that fall within a three-kilometre radius of apartments that can provide treated wastewater. To make these transactions economically viable, it is important that we identify the optimum distance as well as the time taken to cover this distance, loading and unloading.

Three kilometres is a tentative figure and we are doing further calculations based on a successful trial run held on May 31 to arrive at more accurate estimations that would make this whole process even more effective.

Lack of storage tanks in parks is a concern

We have also held meetings with Bangalore Apartment Federation’s (BAF) Yelahanka chapter and other Residents Welfare Associations (RWA) to talk about the benefits of diverting their excess treated wastewater to water green spaces. Even if we are able to secure the cooperation of apartment residents to collect their excess treated wastewater and put in place a tanker network to transport the water, the lack of storage capacity is a barrier to the scaling up of Grey to Green even within these zones.

We found that only 19 of 72 parks in Yelahanka and 13 of 35 parks in Mahadevapura had storage tanks.

Without storage, the tanker’s unloading time is significantly prolonged as it has to stay at the site until the watering is complete as opposed to just emptying the water into a tank and proceeding to the next apartment.

Time, labour and other issues

Moreover, for larger parks, watering directly from the tanker would be time-consuming and labour intensive, which could result in wastage of water.

Also, not all parts of the park would be covered.

Sprinkler systems (like the one in the photo to the right), which address all these problems, can be set up in large parks but this is contingent on the installation of storage tanks.

The process to get this infrastructure set up by the government is long-winded and is likely to take time; different BBMP departments are involved and calling for tenders and allocation of work is time-consuming. But this is an important area of concern that needs to be looked into.

Public parks and green spaces figure high in urban climate resilience and greening priorities because of its potential to sequester carbon and abate heatwaves and floods. But when large sections of the population struggle to source enough water for their basic needs, it is hardly appropriate to make the case for better-maintained parks. Grey to Green could be part of the answer, and mapping parks is a critical first step.

The authors began this work when they were with the Centre for Social and Environmental Innovation at the Ashoka Trust for Research in Ecology and the Environment (CSEI-ATREE).

Edited by Kaavya Kumar

If you would like to collaborate, write to us. We would love to hear from you.

Follow us and stay updated about our work: