Field Notes from Raichur: How People are Working to Restore Common Land

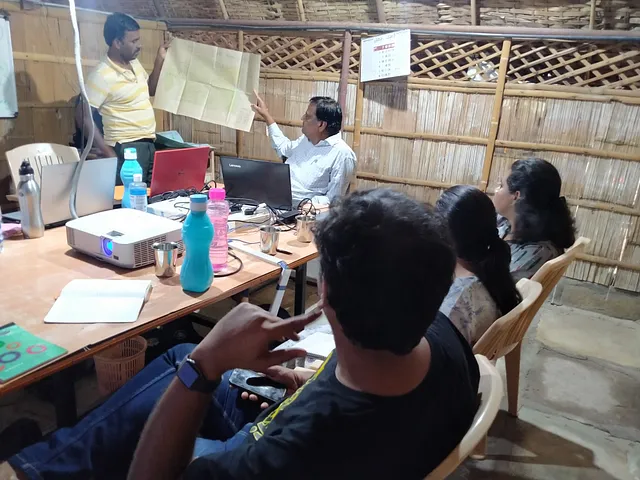

Farmers and NGO workers with Prarambha guided us on the state of lands in parts of Raichur district. Photo by Manjunatha G

‘Food is something that unites a lot of people,’ said Channayyaswamy, who works with Prarambha, an NGO based in northern Karnataka. Channayyaswamy has 33 years of experience working with rural communities. ‘To bring people together, the first step is to organise a potluck. Then invite all the villagers and eat together. This built some sense of unity among them. And then, the magic happens.’

The ‘magic’ Channayyaswamy was talking about is collectivisation among villagers to protect and manage common land. The Rural Futures team met him in Raichur as part of our research work. We were looking into degraded landscapes and how local communities and organisations are managing.

There are multiple factors to consider for ecological restoration of landscapes. For instance, the institutions involved, people’s needs and aspirations, what farming models are appropriate, and sources of funding. We also came across common refrain in our visits to Raichur — the importance of Common Property Resource Groups.

What are common lands and why does it matter for restoration?

Common land spans over a third of India’s total land area, encompassing water bodies, pastures and forests. Rural communities heavily depend on the commons for water, food, fodder and other resources that support their livelihoods. Some studies have reported that 12–23% of household incomes of the rural poor hinge on access to common land. (Beck and Ghosh, 2000; Iyengar, 1989; Jodha, 1986).

These spaces are also important in terms of conserving natural resources like freshwater and as habitats for biodiversity.

Despite its importance, it is estimated that common lands in many Indian states have shrunk by half over the past five decades.

Some of the reasons are insecure tenure rights, encroachment by private parties and a deficiency of trust in the informal community groups managing them. Large parts have also been classified as ‘wastelands’ in official parlance, which suggests that it needs to be put to more ‘productive’ use. The commons then get eaten up for commercial purposes, displacing local communities.

Given that overlapping property rights and ambiguities in the legal framework and formal classification of land use riddle the idea of the commons in India, contestations over such land persist. In 2011, a landmark Supreme Court’s judgement recognised the socio-economic importance of common lands. This spurred state governments to ensure removal of encroachments and create mechanisms to prevent further erosion of commons. Gram panchayats, local communities and Civil Society Organisations (CSO) began to play a greater role in protecting common property resources.

(It is important to note here that we are not suggesting that management by the communities themselves is without problems. It can be marred by social hierarchies that perpetuate inequities, such as caste-based discrimination.)

Restoring degraded common land in Karnataka’s Raichur

It is against this larger backdrop of developments related to the commons that we approached the work being done in Raichur. This district in southern Karnataka is facing a host of challenges, forcing many people here to migrate to cities like Bengaluru and Pune for work. Degraded soil, poor availability of cultivable land, erratic rain, depleting groundwater sources, fluctuating markets have all contributed to making farming a precarious proposition. It is an extreme environment and yet we learnt that when people collectively manage land, and are supported in their efforts, there is huge potential to transform the landscape.

Most of our insights are drawn from conversations with Prarambha, a local NGO that has been doing extensive work. They restore rainfed degraded agricultural lands in Raichur and Koppal districts, in the arid Kalyana-Karnataka region bordering Telangana. Prarambha has been using MGNREGA funds to encourage rural communities to work on two types of land — private agricultural lands and village commons or gomala lands. Their main focus is on non-pesticide management (NPM) of crops.

Prarambha has so far mapped 190 villages in Raichur’s Devadurga taluk and 70 villages in Koppal district, amounting to around 60,000 acres of land.

The Rural Futures team speaking to local community leaders and farmers to understand the challenges they face and the path to restoration they envisage. Photos by: Manjunatha G

How Prarambha helps villagers form Common Property Resource (CPR) groups

Continuing on from the anecdote we began the piece with, once villagers are brought together, they are asked to form groups based on what they are comfortable with and mandated to nominate a representative. These representatives go on to become chief members of CPR collectives. They are empowered by the whole village to take decisions regarding the commons on their behalf.

The next step is to identify the land that constitutes the village commons.

The CPR found that the map of the commons looked different on the ground as many sections had been encroached upon. Interestingly, representatives from the community itself made up the CPR, and the encroachers too were from the same village. This made it possible to hold constructive discussions to withdraw from common land and prevent further encroachment.

The next part of the work is to decide what needs to be grown on the land and how to manage the resources for cultivation.

Through our conversations with Prarambha and farmers in Gajaldinni and Mukkanal villages, we found that in common land that had better access to water, fruit-bearing trees were planted. All the harvest was then tendered to a buyer who would make the payment to the CPR.

In common land with little to no access to water, the villagers grow fodder for their livestock. This essentially meant that there would be no more free grazing in that area. If cattle owners needed the fodder, they would have to pay a certain amount to the CPR, cut the fodder and take it to their base. This became one revenue stream for the CPR to maintain itself. Growing fodder grass also helped arrest soil erosion. Protecting sections of common land thus becomes important to prevent livestock from grazing as this can lead to compaction of soils, degrading its cultivable quality further.

Identifying degradation and working towards restoration

Given the state of soils in this region, rural communities have a list of telltale signs that indicate the extent of degradation. For example, high levels of erosion along streams was a sign of degradation. Another example is the presence of plants with root systems that grow deep and wide. This indicates that the land is good. A thumb rule is that greater the diversity of plants growing on a tract of land, the better the quality of land.

The process of restoration is slow and tedious in a region affected by multiple drivers of degradation from overuse of pesticides to salinity. It’s laborious, the impact on crop yield needs to be studied more systematically, and road access must be improved for the kind of meticulous work needed to bring soils back to life.

A traditional method of converting saline soils to productive land is a good example to demonstrate the extent of work involved. This involves growing a mix of monocots, dicots and oil seed crops over saline land during the rainy season for 45 days, after which they are harvested, returned to the soil and mixed to turn into humus and left for year. This is repeated another year and it is by the third year that the land revives to a semi-productive state and is suitable for growing more crops. But as evident, this is very slow, forcing farmers to turn to chemical fertilisers that have tangible results instantly.

We found that a more sustainable method that is showing promise is the digging of trench-cum bunds (TCB) or earthen embankments that help conserve rainwater, recharge water tables, preserve soil moisture and reduce erosion. We were told that a barren hill transformed after a rainy season once TCB was implemented; tree saplings took root, erosion reduced and birds and animals species in the area increased.

Ecological restoration is complex and requires multiple actors

Some panchayats in Devadurga taluk in Raichur have begun to take on such work — digging trenches, thus improving water-holding capacities and soil moisture levels, and enriching local biodiversity — on priority based on the action plan Prarambha submitted on CPR management.

We have written before about how complex ecological restoration is and that it involves the participation of multiple stakeholders to carry out effectively. An important part of this process is the work of CPR groups and villagers who depend on common land. As next steps, we are looking to identify around 50 hectares of land in Devadurga taluk — a mix of private and common lands that are degraded — and work towards scaling solutions that work.

We are working closely with local partners like Prarambha, as well as the farming communities who are worst affected by degradation, to co-create interventions in these landscapes. We are currently analysing the data collected from an aspirations study in three villages — a unique method that reveals vital insights about what people in the region need to improve their well-being — and will soon share updates about this work.

Credits

The authors conducted this work when they were with the Centre for Social and Environmental Innovation at the Ashoka Trust for Research in Ecology and the Environment (CSEI-ATREE). WELL Labs is now taking it forward in collaboration with ATREE.

Edited by Kaavya Kumar

If you would like to collaborate with us outside of this project or position, write to us. We would love to hear from you.

Follow us and stay updated about our work: