Field Notes from Sittilingi Valley: How a Farmer Collective Addresses Both Healthcare and Agrarian Distress

In the shadow of Kalrayan and Sitteri hills in northern Tamil Nadu’s Dharmapuri district lies Sittilingi, a village that is predominantly home to Adivasi communities. Around 5,000 families inhabit 24 hamlets; Malayali Adivasi groups live in 21 of these hamlets, a once nomadic community called Lambadi live in two hamlets, and one hamlet is inhabited by a Dalit community.

Owing to its almost island-like remoteness, Sittilingi lacked active government administration in the early years post-independence. On one hand, this helped the region retain its tribal culture and natural heritage, but on the other, the people here experienced neglect in terms of healthcare.

To address this, doctors from a town called Gandhigram, about 250 kilometres away, started the Tribal Health Initiative in 1992.

A view of the valley from the surrounding hills. Credit: Nishant Seth

A collective for the people

The initiative’s core ideology was that a community can take care of itself — local women were trained as health workers, auxiliary nurses and midwives both to assist doctors and to take healthcare to the villages.

A natural extension of this work was to improve nutrition, and this led to the Tribal Health Initiative’s efforts in organic farming over the past decade and a half.

The resulting Sittilingi Organic Farmers Association (SOFA) is an interesting case study on how farmer collectives founded on strong community values can benefit small and marginal farmers, as well as the local ecology.

SOFA is among five collectives we chose for a study of institutional structures. The report (to be released soon) delves into the different designs that farmer collectives can adopt in different socio-economic settings. This blog focuses on the story of SOFA.

Nutrition was key: From healthcare to farming

THI found the underlying causes of most health issues in the valley to be two-fold. One was poor nutrition as people in the region depended entirely on government ration, which did not include multiple sources of nutrition like fruits and vegetables, and often was of poor quality. Second, Sittilingi farmers migrated to other places in search for seasonal work and came back with serious health issues as they lived in poor conditions without access to basic infrastructure in the places they moved to. It understood health as something strongly linked to economics, food and education.

This holistic view was adopted by the organisation and its founders, Dr. Regi George and Dr. Lalitha Regi. They came to this conclusion at the end of a six-month long padayatra (journey by foot) that they conducted in 2003.

During the padayatra, visiting villagers and talking to them directly, THI was able to get a deeper understanding of the problems people face. They also got a glimpse at a possible solution — a few farmers had resumed organic cultivation.

Among these pioneers was Selvaraj, who is now the president of the local Farmer Producer Company (FPC). Previously, like most farmers in the valley, he was using fertilisers and growing only paddy. But he could also recall a time when all agriculture was organic and a diverse variety of millets, pulses, tubers, spices, oilseeds and fruits were grown.

One of the first farmers to go organic, Selvaraj (extreme left), is giving a tour to students from Chennai. Credit: Nishant Seth

These insights were followed by further on-ground studies in Sittilingi

After the padyatra, systematic field and market studies were carried out to understand the economic viability of organic cultivation; THI set up a one-acre model farm to compare organic and conventional cultivation of cotton. Around four years of study indicated that organic farming involved less input costs but more labour hours, equivalent yield, and higher prices (₹60/kg vs. ₹50/kg for cotton). These results were attractive, and the number of organic farmers in the valley grew from four in 2004, to 40 in 2008. In 2009, 57 farmers registered themselves as members of SOFA.

In November 2015, the Sittilingi Valley Organic Farmers Producer Company Limited (SOFPC), an FPC, was formed to manage growing sales. SOFPC enables farmers to market produce under their own brand (Svad) and expand their customer base from a few retailers and exporting agencies, to hundreds of direct consumers. As of 2022, it has 500 members. Although this represents only 10% of the farmers in the valley, it is a growing number.

Among multiple metrics of SOFA’s success, three stand out.

-

- It mandates member farmers to set aside part of their land to grow paddy, millets, and vegetables for their own consumption, leading to improved nutrition.

- It has increased and stabilised incomes by offering fair procurement at above market prices, leading to reduced work-related migration.

- Its organic practices have helped soil biodiversity, water health, and the revival of interdependence between farming, livestock, and forests.

These benefits address a wide range of challenges that are not unique Sittilingi. Many parts of India are undergoing environmental degradation and agricultural distress, affecting the well-being of rural communities and making it necessary to explore whether such success stories can be scaled.

The SOFA Model

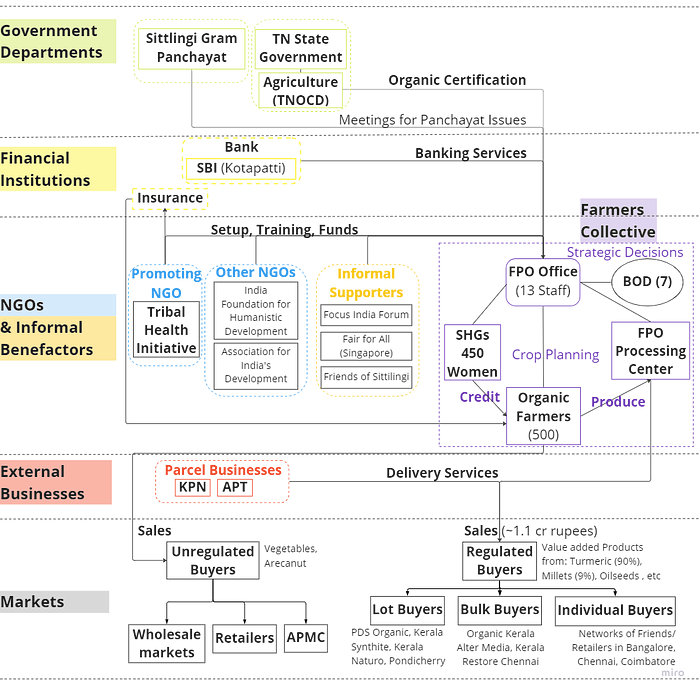

Based on a visit to the SOFPC office, interviews with office and field staff and the current CEO, as well as a visit to a member’s farm, we have visualised the design and workings of the farmers’ collective as a stakeholder map:

Stakeholder Map: The functioning of SOFPC involves coordination between multiple stakeholders; their interrelationships are shown above. (This map is an elaboration of a more general Land Restoration Stakeholder Map)

As can be seen in the figure, the state government is involved in organic certification, and SOFPC staff engage with the gram panchayat for better local governance. However, while other FPCs are supported by the likes of the National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development (NABARD), its public-private subsidiary NABKISAN, the Small Farmers’ Agri-Business Consortium (SFAC) etc, SOFPC has no financial dependence on the government. This is both because of the remoteness of Sittilingi valley and the spirit of self-reliance that THI believes in.

THI, other NGOs, and organised networks of supporters provide support for infrastructure (such as buildings, machinery) as well as working capital.

Above: Drying and cleaning of millets in the processing centre at Sittilingi. Credit: Nishant Seth

THI provides support in multiple other ways

It provides salaries to FPC staff and invests in the education and training of local youth to take up management roles in the FPC.

MoUs are drawn up with buyers in advance, before the growing season, and prices for various crops are fixed at 5–20% above market rate. Once the farmers receive this price list, they draw up their cultivation plans for the year based on their needs. FPC staff document these plans and use it to plan the logistics of processing, value-addition, and transportation. Through the year, members bring their harvests to the collection centre, and get receipts that they take to the office to encash. Their produce is assessed, weighed, cleaned, sorted and stocked. The collection centre employs mostly local women (members of THI-promoted SHGs) to do so.

MoUs are drawn up with buyers in advance, before the growing season, and prices for various crops are fixed at 5–20% above market rate. The price list is communicated to farmers, who then draw up their cultivation plans for the year based on their needs. These plans are documented by the FPC staff and used to plan the logistics of processing, value-addition, and transportation. Through the year, members bring their harvests to the collection centre, and are given receipts that they take to the office to encash. Their produce is assessed, weighed, cleaned, sorted and stocked. The collection centre employs mostly local women (members of THI-promoted SHGs) to do so.

Above: Organic turmeric fields in Sittilingi. Credit: Nishant Seth

Victories and challenges

In its eight years of operation, SOFPC has expanded in terms of membership, processing, value-addition and turnover. It has helped improve income, nutrition, health, employment, and civic engagement.

Like most FPCs, however, it must depend on external sources for access to credit. While it makes a net profit by the end of the year, peak-season procurement requires large capital. Currently, its promoting institute, the THI, and network of benefactors are able to provide this, but the future might require it to have other sources. It also faces challenges due to remoteness: unreliable electricity and lack of access to quality machinery.

SOFPC plans to diversify its consumer base and possibly overhaul its overall design — like most FPCs, it must keep evolving. But its core approach of investing in the training of local people and in the reciprocal relationships between health, food, and economics, is yielding results.

Credits

Acknowledgement: This research could not have been carried out without the help, cooperation and guidance of SOFPC staff, in particular field staff P. Durai.

The authors conducted this work when they were with the Centre for Social and Environmental Innovation at the Ashoka Trust for Research in Ecology and the Environment (CSEI-ATREE). WELL Labs is now taking it forward in collaboration with ATREE.

Edited by Meghna Majumdar

If you would like to collaborate with us outside of this project or position, write to us. We would love to hear from you.

Follow us and stay updated about our work: