A Visionary Architect and a New Growth Model: What’s Behind the Rise of Sponge Cities in China?

Dong’an Wetland Park in the city of Sanya in China’s Hainan Island, an example of a sponge city designed by Kongjian Yu. Credit: Turenscape

Kongjian Yu was only 10 years old when he witnessed the power of nature firsthand. Heavy rain caused the creek near his village in China’s Zhejiang province to swell and spill over to the rice terraces. When he ran to the river’s edge in excitement, he slipped into the surging floodwaters. Fortunately, he was able to save himself by grabbing onto the willow and reed vegetation that grew all along the banks. Decades later, in an interview with BBC, Yu said:

‘I am sure that if the river was like it is today, smoothened with concrete flood walls, I would have drowned.’

This experience had a profound impact on him, inspiring him to become a pioneer in the field of sustainable urban design.

Timely intervention helped sponge cities address multiple issues

Yu is widely credited with the concept of ‘sponge cities’, implemented in China at a time when the nation was grappling with the adverse effects of rapid urbanisation – severe flooding, water pollution and water scarcity. In 2014, 641 of 654 Chinese cities surveyed reported frequent flooding. Another study revealed that 45% of Chinese cities faced water supply shortages. To manage floods better, China instituted a nationwide sponge city programme in 2014, integrating blue-green infrastructure over existing grey infrastructure.

In the second part of our blog series on this nature-based solution, the Urban Water programme at WELL Labs summarises the driving forces that led to the implementation of this programme.

Read Part 1 | Soak Up the Rain: What is a ‘Sponge City’ and Can it Make Urban Areas More Climate Resilient?

Kongjian Yu is now the Dean of the College of Architecture and Landscape at Peking University and the founder of Turenscape (‘Tu’ means earth, ‘ren’ means people). It is one of the first and largest landscape architecture firms to practise sustainable urbanism in China.

A revival of ancient techniques in green infrastructure

Yu’s childhood experiences also shaped his vision for repairing humans’ relationship with water. Growing up, he observed Chinese ‘peasant wisdom’ where farmers managed water, by maintaining ponds and berms to store and harvest rainfall. As China urbanised, however, this knowledge was abandoned in favour of grey infrastructure.

Yu believes that we need to make friends with flooding. He recommends ancient techniques that work with the water by slowing down surface run-off by harvesting it in ponds and constructing meandering rivers with vegetation or wetlands.

On the left, is a picture of terrace farming of rice in China’s Yunan province (credit: Vince Russell on Unsplash). Kongjian Yu grew up watching farmers manage water by storing it in ponds . On the right, is a photograph of the Sanya Mangrove Park in Hainan. Here, the mangroves within the ‘interlocked fingers’ catch and filtrate the stormwater from the urban pavement and road, creating public spaces at different elevations (credit: Turenscape).

Yu’s philosophy in landscape architecture, known as the ‘Art of Survival’, draws inspiration from the historical water management practices of Chinese farmers. It combines functionality and beauty to create landscapes that are guided by ecological sustainability, multi-functionality, cultural context and community participation.

Recognising the flood-control and recharge capabilities of natural systems, Yu conceptualised the sponge as a metaphor for efficient water management. The concept took shape in the first pilot, Zhongguancun Life Science Park in 2000, where rainwater was collected and purified through an innovative artificial wetland.

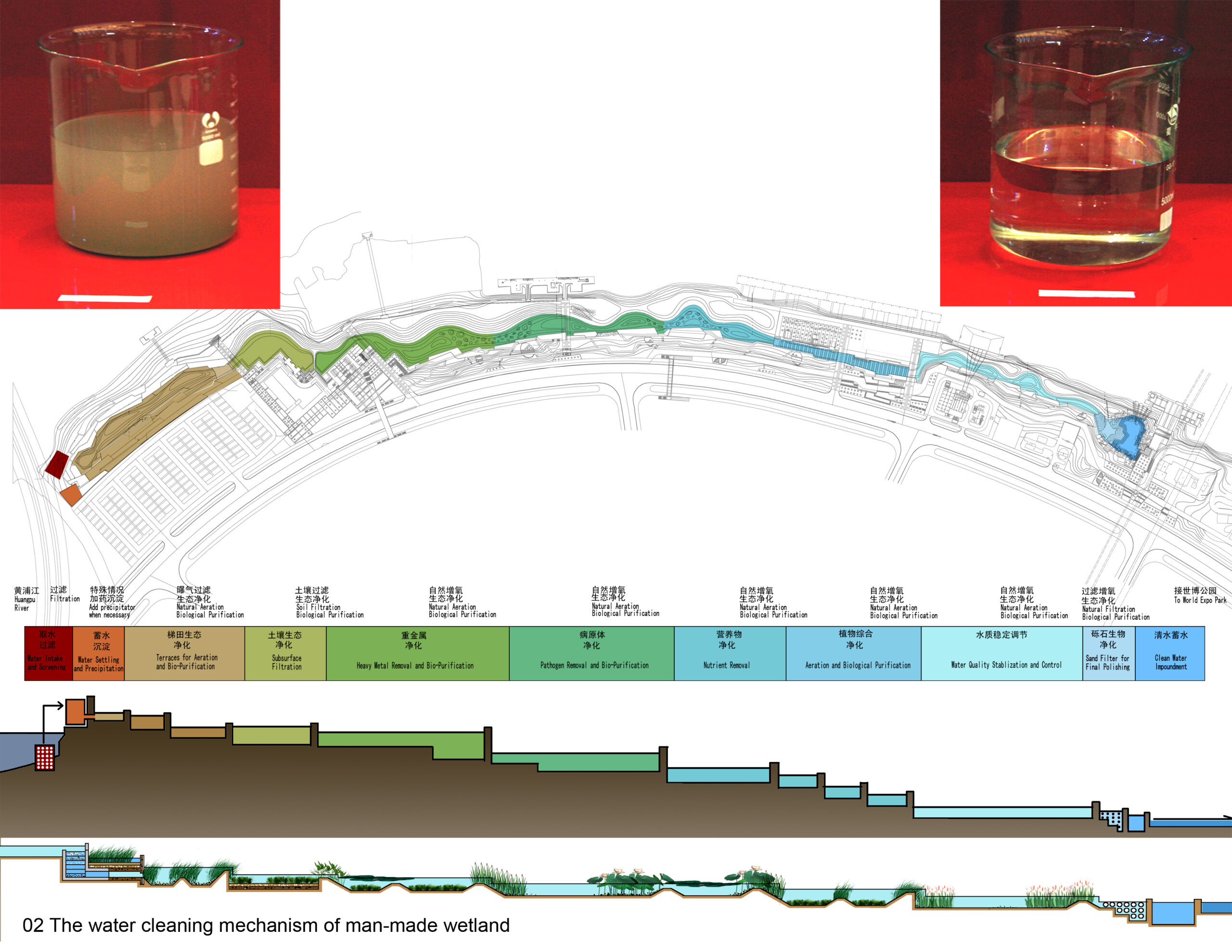

This image by Konjian Yu, Turenscape and Peking University, illustrates how a constructed wetland system (or blue-green infrastructure) purifies river water. The quality of the water is evident from the pictures of the beakers – the one on the left is murky and not fit for use, while the one on the right is significantly cleaner. This graphic captures what’s at play in Houtan Park, a regenerative ‘living landscape’ on Shanghai’s Huangpu riverfront. More pictures of the terraced wetland system are available here.

Yu launched the concept of ‘Inverse Planning’ to reverse the damage caused by conventional planning procedures. This emphasises the protection of existing natural functions and advocating for preservation over development. To that end, he tirelessly engaged decision-makers at various levels; for instance, he delivered more than 1,000 lectures to mayors and ministers. In 2006, his proposal to then Prime Minister, Wen Jiabao, on initiating national-level research on ecological security was sponsored by The Ministry of Environmental Protection. Since this report was published, the State Council has issued four state regulations to guide land use and planning in order to maintain ecological security.

Yu emphasised an ecology-focused approach to policy

In his influential book, ‘Letters to the Leaders of China: Kongjian Yu and the Future of the Chinese City’, he amplified his advocacy efforts by directly addressing political leaders and policymakers. These letters served as a call to action. They urged leaders to prioritise preservation of nature, promote green infrastructure, and embrace a more holistic approach to urban development.

Yu’s dogged efforts over a decade played a critical role in fuelling the adoption of sponge cities. But this needs to be understood alongside the context of governance in China.

The failure of the heavily industrialised model and the reconcentration of power

For decades, China had been following the economic growth model to grow at breakneck speed. The pollute-first-clean-up-later approach had led to widespread pollution and environmental damage. And then, in 2007, President Hu Jintao of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) first endorsed ‘ecological civilisation’, a people-centred, sustainable new development model. The CCP’s promotion of this concept was a political response to the state’s failure to protect the environment, threatening political stability.

At the end of Hu’s term, there was a rise in environmental unrest and severe criticism of the failure to transform China’s economic development model. The task of reforming the industrial model then passed to his successor Xi Jinping, the current President. He promoted a top-down model of ecological transition. His series of centralisation reforms in 2012 led officials to concentrate power under his leadership. In fact, this push for ecological civilisation was really a push for rule of law. For instance, central government control was strengthened to redress an imbalance in socio-economic development. By placing governance reforms at the heart of the green economy transition, Xi was able to do what his predecessor could not, opening the doors to more sustainable models.

Read | Why We Need Urban Water Balances

Yu’s team took advantage of the top-down political system and gave presentations on the sponge city concept and ecological restoration mandating it for government officials of all ranks. Public mass media was also extensively used for rebroadcasting a presentation series, which helped build broad community-level support.

Frederick Steiner, dean of the University of Pennsylvania Stuart Weitzman School of Design, describes Kongjian Yu as a ‘master of merging global ideas and applying them in the Chinese vernacular’.

An Olympic turning point for sustainable architecture

The Olympics also played a role in fuelling the adoption of the sponge cities concept. Beijing had been in contention for hosting the Olympics since 1992. However, it lost the bid due to environmental and mobility concerns. In 2001, China finally won the bid to host the Summer Olympic Games of 2008 on a $42.3 billion budget. It was decided that 42.2% of investment earmarked for organising the games would be used to improve the environment of the capital city. This was a turning point for sustainable landscape architecture in China.

Turenscape contributed to the Beijing Olympics by completing numerous projects facilitating these environmental goals while successfully integrating his sponge concepts. The Chaoyang Volleyball Park, an erstwhile factory, is one such project, serving as a proof-of-concept of the sponge city model.

Flooding brought sponge cities back in focus

Just four years after the Olympics, Beijing faced severe flooding. Yu’s team promptly drew attention to flood mitigation success of green infrastructure at Qiaoyuan Park, Tianjin and Qunli stormwater park, Harbin. After having worked on sponge concepts for over a decade, it finally found its place in national strategy after President Xi spoke at the Central Urbanisation Working Conference in December 2013.

Through intersections of Kongjian Yu’s journey and China’s evolving political movements, we can gain insights on integrating sustainable planning and design into the growth fabric of a nation. Yu’s demonstration of sponge city concepts through a series of captivating pilot projects, his data-backed academic research to influence the government, his ability to blend scientific thought with cultural context coupled with state reforms to spur a green transition led to the watershed moment – nationwide adoption of the sponge city model.

Edited by Kaavya Kumar

If you would like to collaborate, write to us. We would love to hear from you.

Follow us and stay updated about our work: