Why We Need Urban Water Balances

Bengaluru’s water crisis — A tale of mismanagement

Bengaluru’s water problems may sometimes seem contradictory. Stories of drying borewells and lakes compete with outcries about flooded streets. But these twin water problems are clearly interconnected — it is a question of balance.

Growing demand for land in the city is reflected in a dramatic increase in urbanised land-use over the decades. The consequent encroachment of wetlands, replacement of green spaces with concrete, and the gradual loss of interconnectivity between lakes are one reason for increasing flash floods.

With abundant rainfall (>900 mm annually over the last five years) and little room for recharge, wells run dry as drains overflow. Despite being allocated Cauvery water, the expanding city, particularly the newer suburbs, has become increasingly dependent on groundwater. So, groundwater depletion is a problem.

Even as consumption has increased, the amount of wastewater treated by centralised infrastructure is only about 50%. (This is based on conservative government estimates on the total wastewater produced by the city). This has serious implications on the quality of existing surface and groundwater resources.

To address the crisis, we need a better understanding of Bengaluru’s water system

Local efforts are being made in response to different facets of the problem, considering the city’s growth has long outpaced state infrastructure. The applicability of decentralised and low-cost technologies — rainwater harvesting, groundwater recharge and wastewater treatment — have been demonstrated in Bengaluru time and again. Bengaluru is second on the list of Indian cities that have the most number of rainwater installations. Regulations for property owners to upscale rainwater harvesting are on the rise. Innovative green infrastructure systems (1, 2) to treat polluted water are being implemented. Examples of citizen-led efforts to locally manage wastewater are plenty (1, 2). At a broader scale, campaigns to rejuvenate groundwater, restore lakes and revive drainage canals have gained traction.

The challenge that remains is that many of these efforts are being implemented in small scales, by different groups of stakeholders. There is no overarching strategy.

Clearly, the city is in need of an integrated urban water balance and management plan. However, some immediate questions that emerge are: where is Bengaluru’s water, how much is there and in what condition?

Urban water systems consist of complex patterns

These include patterns of water extraction, consumption and discharge, all bound by the city’s broader hydrological context. All of these would play a part in an urban areas water balance.

To elaborate on the case of Bengaluru, the city relies on two main water sources extracted from within and outside its watershed. Around 1,460 million litres a day (MLD) of water from the Cauvery is transported from a reservoir 90 km away from the city. Groundwater, fed by seasonal rains through lakes and green spaces, is an important supplementary source. However, the exact amount of groundwater extracted daily is challenging to estimate due to the range of informal mechanisms through which urban activities access groundwater.

Public water supply, delivered by the Bangalore Water Supply and Sewerage Board (BWSSB), is concentrated in central areas of the city, where the population is lower than in rapidly growing suburbs. Where public infrastructure is absent, consumers, including a majority of commercial entities, have turned to groundwater accessed through private borewells, tankers and open wells.

A small, but growing, number of residents and institutions are supplementing their needs with rooftop rainwater. The resultant wastewater is treated, reused and/or discharged through a variety of channels. Centralised sewage treatment plants (STPs) in Bengaluru treat only about 715 MLD. Decentralised treatment plants supplement public infrastructure, but they are more challenging to manage and monitor. The remaining wastewater generated by the city goes untreated, often finding its way into lakes and groundwater.

The city’s hydrological characteristics are crucial to how these flows occur.

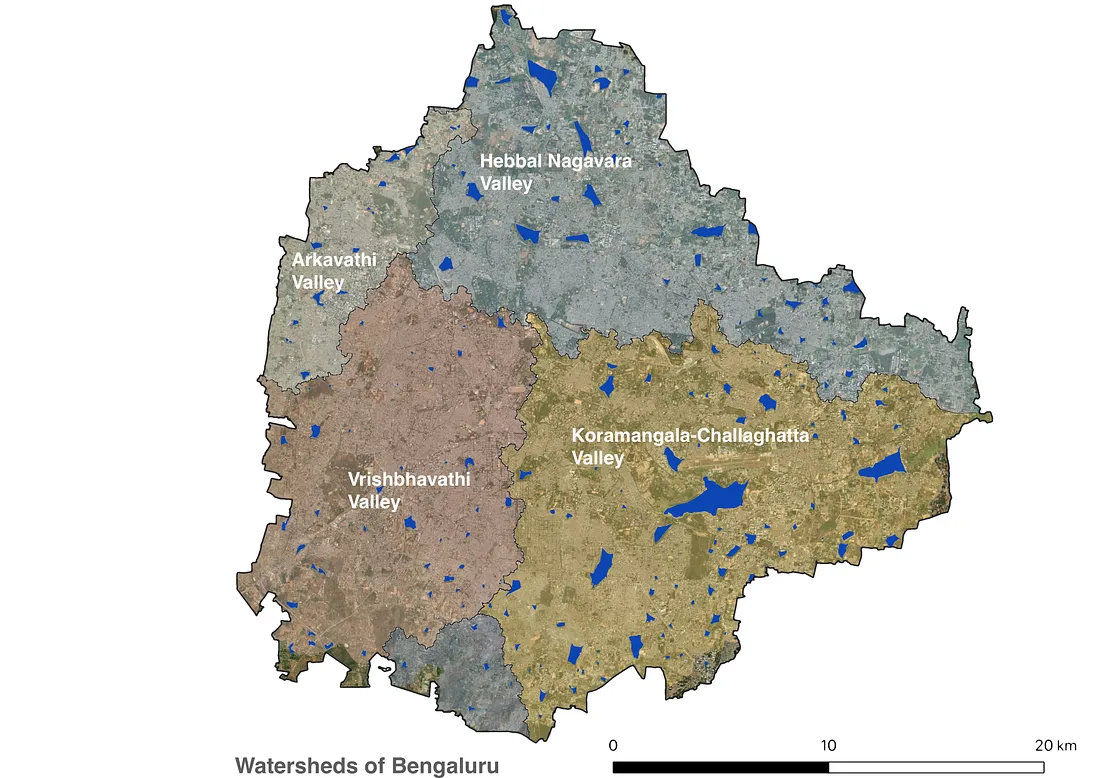

For instance, water drainage patterns are influenced vastly by Bengaluru’s undulating terrain. The undulations are also why Bengaluru’s network of lakes and channels are pivotal to managing urban floods — the lake system was designed to manage surpluses by allowing water to cascade from one lake to another. Further, Bengaluru is divided hydrologically into three major watersheds. The Vrishabhavathy-Arkavathy valley drains into the Cauvery basin, whereas, the Hebbal and Koramangala-Challaghatta valleys drain into the Dakshina Pinakini river. The watersheds are unique in their characteristics — they vary in terms of soil, topography and even groundwater recharge and storage capacities.

Lastly, seasonal fluctuations in freshwater availability is another key factor. The fluctuations are primarily driven by the concentration of rainfall between June to November. After lakes fill up as the monsoons start, even light showers can flood the city when the water has nowhere to go. Consumption patterns fluctuate too. Green spaces and the construction industry consume more water during drier months. Domestic consumers are more likely to be dependent on water tankers when their borewells are running dry in the summer. Several interventions, such as rainwater harvesting and green infrastructure, can be planned to balance water availability between wet and dry months. However, a starting point for planning is to understand how the fluctuations look across various stages of the urban water system and how significant they are.

The urban water balance chart — why is it important for Bengaluru?

A City Water Balance is a summary of all flows in the urban water system. It provides a quantified basis for urban flows; water resources feeding the city, areas of significant usage, losses, discharge and storage.

A number of data points are needed to develop the chart — these include data on hydrogeology, topography, land-use & land cover, demography, consumption patterns across sectors, etc.

The consolidated data is visualised as a ‘water flow diagram’ to understand how water moves through different parts of the urban water system. For example, information on Bengaluru’s allocated water from the Cauvery may be easy to find. But how much water actually reaches consumers? How much groundwater is extracted to supplement the city’s needs? How much is being recharged back underground? Information on the capacities and location of Bengaluru’s centralised wastewater treatment plants is available. However, how much of Bengaluru’s wastewater currently being treated is really being repurposed? How much wastewater goes untreated and where does it end up?

The water flow diagram accounts for all the water flows within the system, including the interdependencies. Through this process of mapping, the water flow diagram is also useful in identifying knowledge gaps.

Taken a step further, the water flow diagram can be used to assess the implications of potential interventions too. If the city was to maximise its wastewater reuse, how much would it reduce the pressure on the Cauvery? If all building roofs harvested rainwater for consumption, how would it change the city’s dependence on groundwater? What area of green spaces and wetlands need to be protected or reclaimed to effectively address seasonal flooding?

The possible discussions stemming from a City Water Balance are many. Fundamentally, when there is a comprehensive overview of the various processes occurring within an urban water system, it becomes easier to analyse how strategies can simultaneously address multiple dimensions of water security planning.

Credits

The authors conducted this work when they were with the Centre for Social and Environmental Innovation at the Ashoka Trust for Research in Ecology and the Environment (CSEI-ATREE). WELL Labs is now taking it forward in collaboration with ATREE.

If you would like to collaborate with us outside of this project, write to us. We would love to hear from you.

Follow us and stay updated about our work: