The Green Rural Economy Initiative: ‘Servicifying’ the Social Sector

A focus group discussion with community resource persons in Bahraich district, Uttar Pradesh. Photo by Gargi Anand

The Why: Communities Don’t Know Where to Find Solutions to the Problems They Have

Sabanna* is a dryland farmer in Raichur, Karnataka, who depends entirely on rainfall to grow a single crop in a year. With no alternate water source and land degraded by years of excessive chemical use, he struggles to restore soil fertility. Lacking the resources to revive his farm, he produces just enough to survive but not enough to sell.

Rural communities across India face similar challenges, further exacerbated by climate change. Practices like monoculture and heavy chemical use—widely promoted during the Green Revolution—have depleted natural resources, degrading soil health and water availability. Declining agricultural yields have forced many farmers to leave their villages in search of precarious jobs in cities.

Sabanna, who aspires to improve his income and diversify his livelihood, approaches a local civil society organisation (CSO) to explore the possibility of groundwater collectivisation. He hopes this will allow him to grow fodder as a second crop. However, the organisation lacks expertise in this area.

While there are CSOs that focus on entrepreneurship and natural resource management, there are none near Sabanna, in Raichur, that can help him find solutions for sustainable groundwater management. Access to knowledge, training, troubleshooting, and essential resources remains limited in India, leaving farmers like him without the support they need.

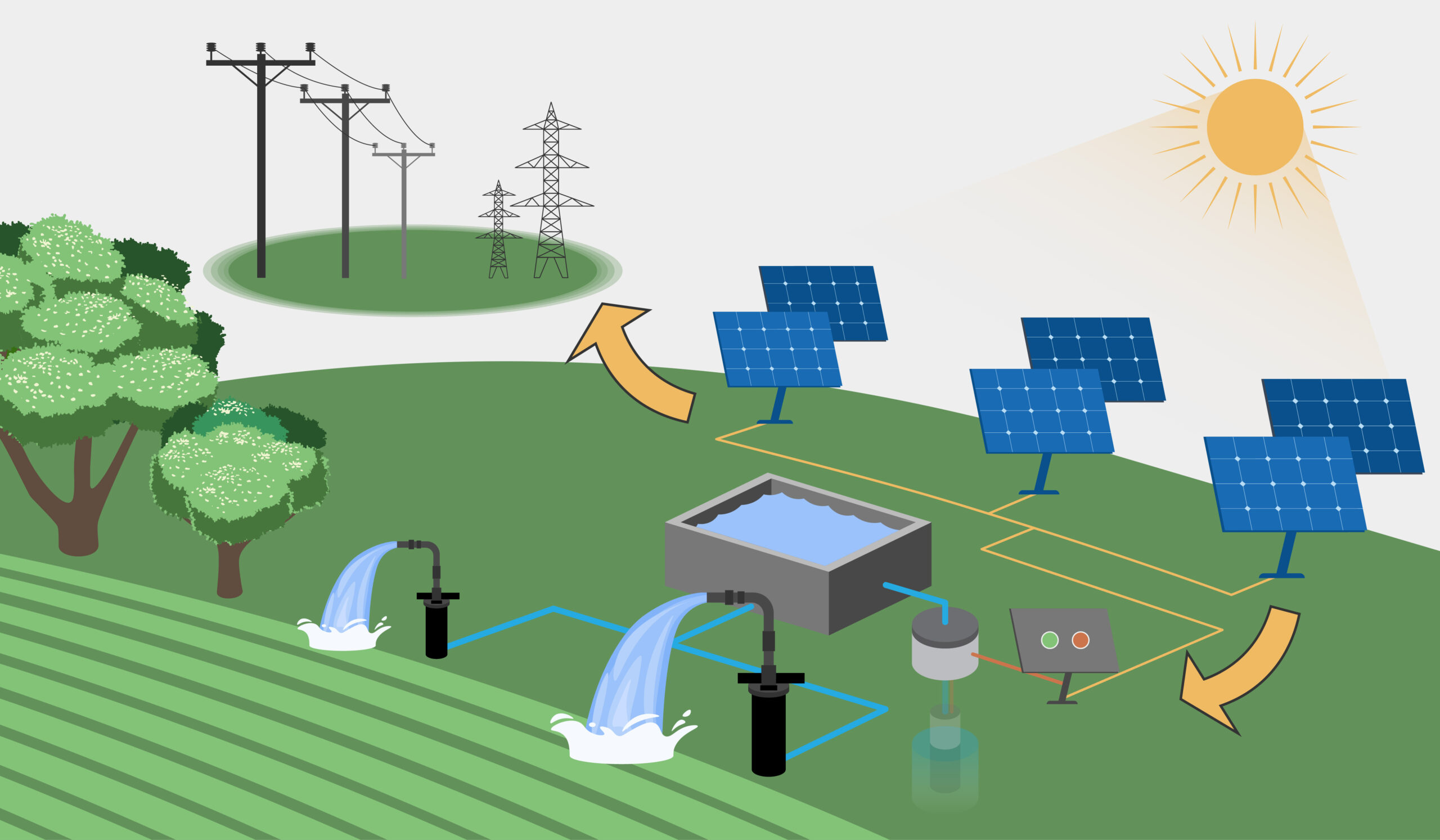

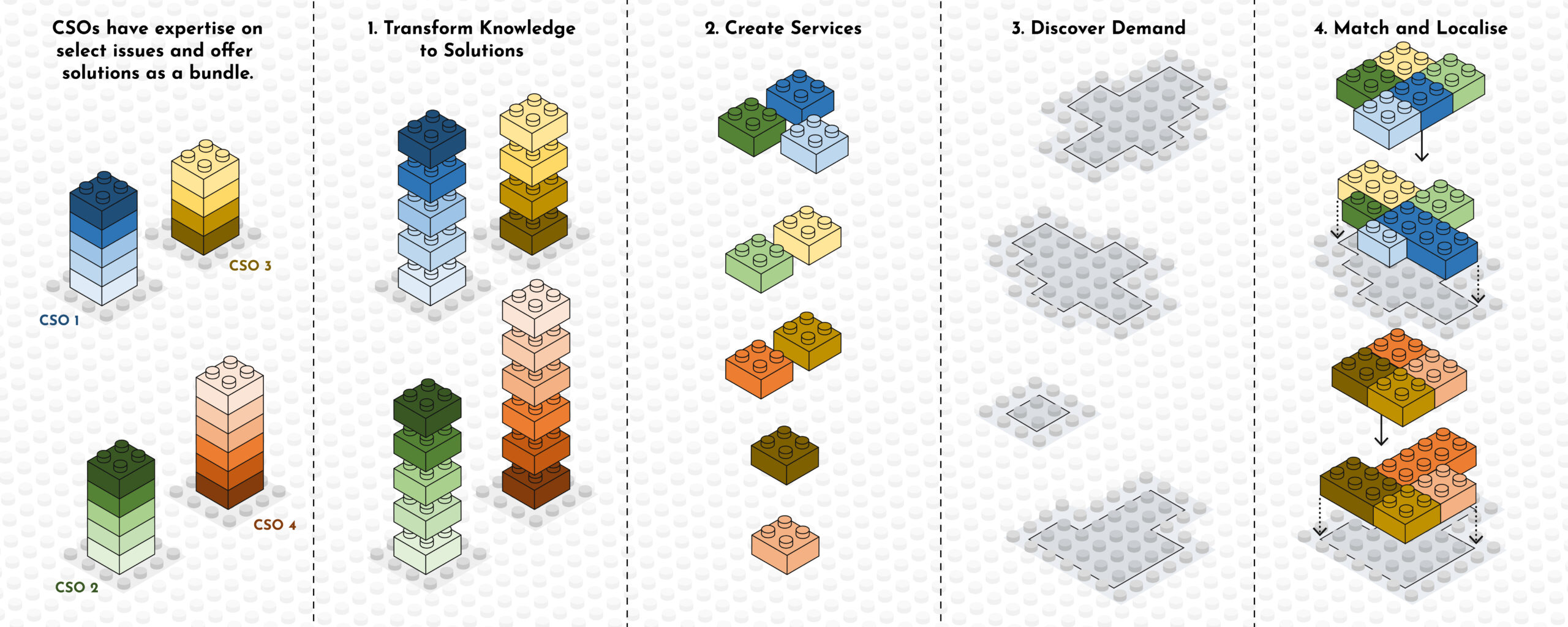

CSOs offer deeply contextual, end-to-end solutions and it’s often unthinkable for them to break up the steps. However, a one-size-fits-all approach doesn’t work for a country as diverse as India. GRE attempts to extract this knowledge in a structured, modular, user-centric manner, and cross-pollinate this to other communities. Concept by Veena Srinivasan and design by Aparna Nambiar.

India has thousands of civil society organisations that have earned the trust of the communities they serve. They have also, over decades, developed solutions that are deeply contextual.

The challenge lies in how these solutions are offered—as complete, end-to-end packages. They often include community mobilisation, capacity building, water structure development, measurement devices, and the creation of local water institutions. It’s often unthinkable for the CSO to break the steps up.

However, different communities have different needs. One may require only measurement devices, while another may need support in governance or capacity building. A one-size-fits-all approach limits the transfer of knowledge and restricts communities to the solutions promoted by the CSO, rather than what might be most relevant to them.

How can we change this? How do we extract this knowledge in a structured, modular, user-centric manner, and cross-pollinate this to other communities? How do we ensure that communities gain exposure to a range of solutions and choose what works for them? This is where the Green Rural Economy (GRE) initiative comes in.

The Green Rural Economy aims to build a response ecosystem for the social sector, accelerating the creation of sustainable, decentralised, and thriving local economies. It does this by curating community demand, connecting solution providers through a dedicated platform, and facilitating knowledge exchange across a synchronised network of civil society organisations, community stakeholders, and donors.

Our goal is to use a networked approach, led by a consortium of organisations developing innovative, green solutions for rural India. GRE aims to bridge the gap between knowledge seekers and solution providers through the idea of ‘servicification’.

The What: Servicification

In the private sector, expertise scales through services. Take an architect designing a house, for example. They talk to the client, understand their needs and vision, and come up with a design. From there, a range of specialists—masons, plumbing contractors, electricians, and carpenters—step in to execute different aspects of the project. The architect doesn’t need to learn plumbing, nor does the plumber worry about being replaced by the carpenter. Each professional is compensated for their specific expertise.

Moreover, architects rarely insist on using a single designated carpenter, plumber, or electrician. Instead, these roles are typically filled from a broader talent pool. Essentially, the entire process of house design is broken down into distinct, serviceable tasks—some of which are standardised and can be fulfilled by a variety of skilled providers. This approach allows solutions to be broken up into components that can be offered as individual services.

Also Read | Downloading the Expert’s Brain: How to Decode Knowledge and Encode it into Solutions

Now, consider a similar scenario in the social sector. Many CSOs are deeply embedded in specific landscapes and effectively act as the ‘architects’ of those regions.

Take, for example, a grassroots organisation, X, based in Uttarakhand that specialises in natural farming. As they work with the community, they follow a structured process to encourage the adoption of natural farming practices. However, at some point, a community member expresses interest in beekeeping—an area where CSO X has no expertise.

In most cases, the idea is simply abandoned due to a lack of know-how. On rare occasions, an enterprising field officer might make inquiries and discover person Y, a beekeeping expert in Himachal Pradesh. But for the interested community member, accessing this knowledge is costly and impractical—they would have to travel at their own expense, learn the process firsthand, and then return to adapt it through trial and error, adding further costs and uncertainty.

Unlike the private sector, where expertise is easily transferred through consultancy services, there is no structured system for communities to access specialised knowledge in the social sector. While funding is one clear challenge, it is not the only missing piece of the puzzle. The absence of a streamlined mechanism for sharing expertise prevents valuable solutions from reaching those who need them.

The Who: Civil Society Organisations, Progressive Farmers, Government Agencies

In the building analogy, an architect can easily connect with a plumber because the plumbing profession has established its expertise. Plumbers understand architectural plans, know where to source materials, and follow specifications without needing to explain the intricacies of hydraulic engineering to the client. Their knowledge is encapsulated into a clear service offering, making it easy to access and apply.

This structured approach is largely missing in the non-profit and public goods sector, where there is no ‘servicification’ of expertise. Take X and Y—experts in natural farming and beekeeping, respectively. While they possess deep knowledge in their fields, there is no established system for them to train and certify others who can then be paid to adapt and implement these practices in different contexts.

Who X and Y are may vary—they could be NGO staff, government extension officers, or progressive farmers. But without a scalable mechanism for transferring their expertise, knowledge remains locked within individuals rather than becoming an accessible service that communities can rely on.

The Social Sector is Not Service-ready

Several factors contribute to this challenge:

- Solutions are tied to landscapes: Grassroots CSOs often identify with both their landscape and their solution—such as ‘We do shrimp farming in Odisha’. This localised approach is ecologically sound but limits the transfer of proven solutions. With minor adaptations, these methods could benefit other regions, yet there’s no structured way to facilitate this.

- Limited problem-solving mindset: Many CSOs see themselves as specialists in a single solution rather than as broader problem-solvers. They enjoy strong community trust, so their proposed solutions are readily accepted—even if they don’t fully address all local challenges. Without a competitive marketplace, there’s little incentive to expand their offerings.

- Knowledge loss due to funding cycles: When project funding ends, CSOs often shift focus to align with new funding priorities—say, from watershed development to climate-smart agriculture. This transition rarely includes a process for preserving and transferring knowledge, causing valuable expertise to fade over time.

- Barriers for newcomers: Young, enthusiastic problem-solvers entering the sector often struggle to find the right resources and connections. The sector relies heavily on informal networks, making it difficult for newcomers who need structured guidance and mentorship.

- Lack of incentives for open knowledge sharing: Unlike the private sector, where people are compensated well, CSO workers value credit and attribution. Many hesitate to share their expertise openly, fearing their solutions may be replicated without proper recognition.

The How: GRE Enables Servification

The Green Rural Economy initiative aims to enable collaboration and the servicification of the development sector by connecting solution seekers (individual entrepreneurs, grassroots CSO workers, and community resource persons) with trusted partners and experts. By mapping community needs and assembling expertise across the rural value chain, GRE expands access to diverse, practical solutions.

To achieve this, GRE leverages a digital platform, alongside in-person and online networking events, to facilitate knowledge exchange. Farmers already gather information through local networks, vendors, extension workers, and even social media. However, certain solutions gain more traction than others, often driven by existing market incentives.

Take agricultural productivity, for example. The market for ‘high-input’ farming—hybrid seeds, pesticides, and fertilisers—is well-developed. In contrast, ‘low-input’ and nature-based solutions lack market incentives, despite their long-term benefits for farmers and the environment.

To address these issues, GRE aims to open up a whole gamut of sustainable solutions.

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by Rainmatter Foundation and Axis Bank Foundation.

Edited by Archita Suryanarayanan and Ananya Revanna

Follow us to stay updated about our work