Promoting Wastewater Reuse, Community Engagement, and Financial Incentives for Water Conservation | Insights from the Urban Water Programme

This blog is excerpted from WELL Labs’ Annual Report 2024–2025.

You can read the report here.

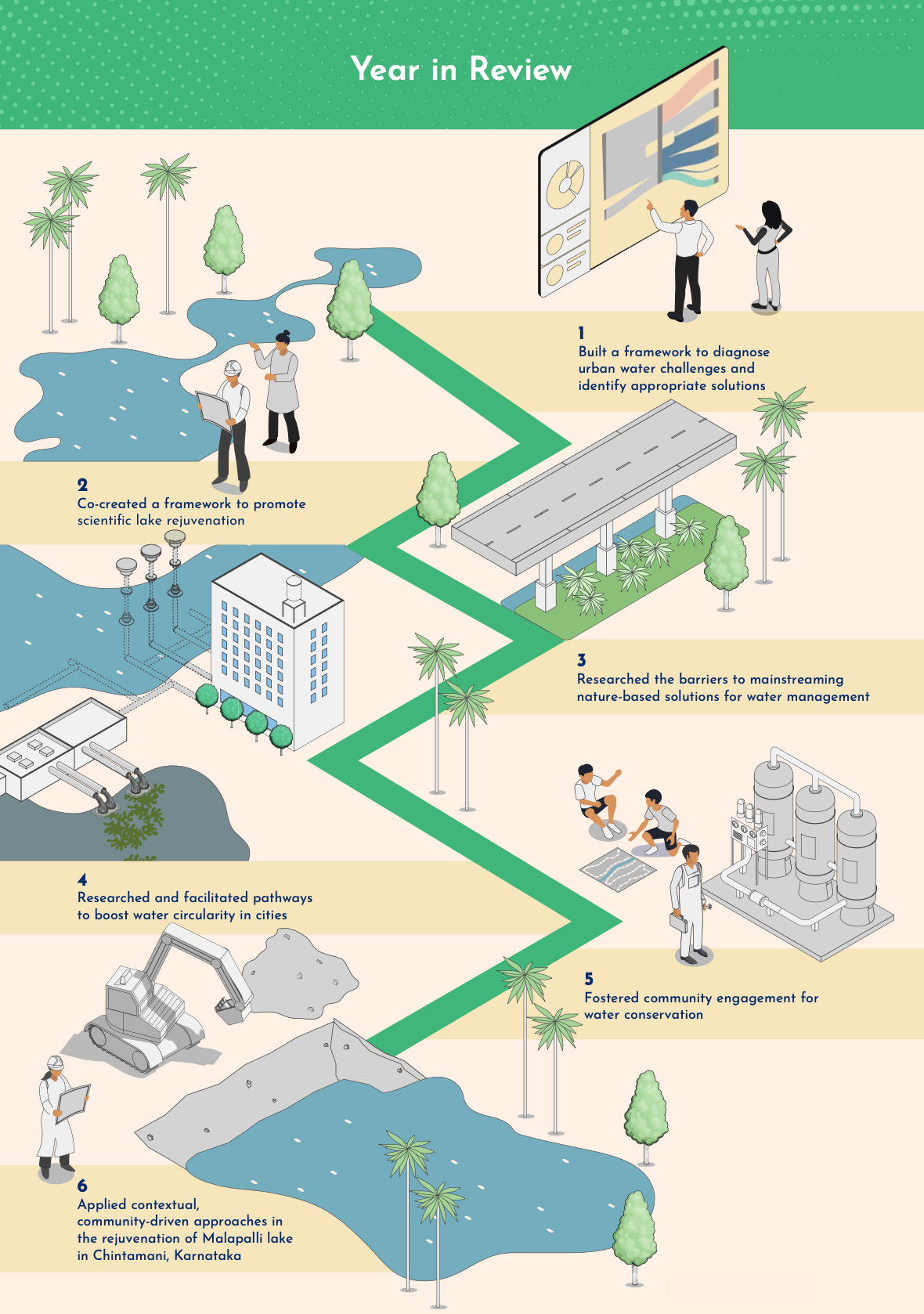

The Urban Water programme designs pathways towards water-secure and resilient cities using water circularity and nature-based solutions. Over the past year, we:

- Built a framework to diagnose urban water challenges and identify appropriate solutions.

- Co-created a framework to promote scientific lake rejuvenation.

- Researched the barriers to mainstreaming nature-based solutions for water management.

- Researched and facilitated pathways to boost water circularity in cities.

- Fostered community engagement for water conservation.

- Applied contextual, community-driven approaches in the rejuvenation of Malapalli lake in Chintamani, Karnataka.

We partnered with Bruhat Bengaluru Mahanagara Palike (BBMP), DCB Bank, Friends of Lakes, Oak Foundation, India Forum for Nature-Based Solutions, Rocky Mountain Institute, Chintamani City Municipal Council, among other organisations for these initiatives.

Illustration by Sarayu Neelakantan

Our work with our partners shaped the following insights:

1. The lack of data regarding urban nature-based solutions in the Indian context is a major barrier to their widespread adoption.

Nature-based solutions, such as parks, ponds, green buildings, and green stormwater infrastructure, have shown significant benefits, such as reducing the urban heat island effect, managing floods, improving groundwater recharge, restoring degraded ecosystems, conserving biodiversity, and creating recreational public spaces.

While there is data regarding these interventions from China and Singapore, among other regions, there is limited data from the urban Indian context. Thus, urban planners, architects, builders, or municipalities find it difficult to quantify the benefit provided by an NbS intervention and the scalability of those benefits, that is, the point at which the NbS system will saturate and not provide the same benefits as it did when the project was initiated.

This data gap also deters the private sector and philanthropies from funding nature-based solutions. Commercial investors require clear, quantifiable data on financial returns and risk profiles. The lack of data on the financial performance and market rates of nature-based solutions means they are perceived as high-risk and low-return compared to conventional alternatives. Philanthropic funders often seek evidence of social, environmental, and economic impacts to justify their investments. In this case as well, the absence of reliable data makes it difficult for them to assess the effectiveness and scalability of their contributions.

Thus, despite their potential, nature-based solutions often struggle to attract sufficient investments. Currently, the majority of funding comes from the government.

2. Financial incentives, such as tax breaks and subsidies, can strengthen efforts to engage communities in water conservation.

Initiatives like the Bangalore Water Supply and Sewerage Board’s Green Star Challenge are crucial to engage communities in water management, promote the adoption of water-saving fixtures, and increase awareness about urban water challenges and solutions.

While acknowledging and commending water-saving practices by assigning high ratings to good performers is important, it is just the first step. Offering tax breaks or subsidies to organisations or buildings with higher ratings could encourage more entities to participate in the challenge and implement water-conservation initiatives. Financial incentives can also motivate organisations and residents to invest in sustainable technologies that might otherwise be prohibitively expensive.

Also Read | How Can We Engage Communities to Conserve Water in Bengaluru?

The Green Star Challenge team inspects a building in Bengaluru

3. Luxury homes in water-scarce areas are the most likely early adopters of innovative decentralised sanitation solutions.

A transition to decentralised sanitation systems can be challenging because the choice of technology is inherently consumer-driven (as opposed to large institutions, such as municipalities, which are more likely to opt for centralised technologies since they would be more cost-effective due to economies of scale). This necessitates a market-driven strategy. To enable this, we need to identify different market segments and map them to suitable solutions, while also factoring in socioeconomic contexts and cultural practices.

Innovative sanitation solutions like Reinvented Toilets are quite expensive. However, their advantage is that they generate clean (near potable) water and ash that is relatively cheap to dispose of. The costs could decrease significantly with an increase in the market size and eventually enable complete water circularity.

It is expected that luxury homes in areas with high water scarcity would be early adopters of innovative technologies, as their residents would have the means to pay for these expensive systems to secure their water availability.

Therefore, focusing on high-end markets in large metropolitan areas could eventually help transform sanitation systems at scale.

4. Water credits can help finance water-management interventions in the same manner that carbon credits have funded sustainability initiatives, such as renewable energy and carbon capture.

While carbon credits are well-established for nature-based solutions, they apply only to projects with direct carbon sequestration potential, such as forest conservation. Water savings are not part of their calculus. To bridge this gap, we need a water credits system to quantify the water savings from nature-based solutions, which will help finance such interventions.

Water credits represent a specific amount of water that has been either conserved or produced. These credits can be traded between entities experiencing water shortages and those with a surplus. While the idea of water credits is comparable to that of carbon credits, a key difference is that, due to the localised nature of water resources, transactions must be confined to the same hydrological unit, such as a river basin or watershed.

The stormwater retention credits (SRC) system, implemented in Washington, DC, is a good example of a water credits system. Since its inception, the programme has facilitated the sale of over 1.7 million credits, equivalent to capturing and treating more than 40 million gallons of runoff annually. Beyond its environmental impact, the initiative has contributed to the establishment of green spaces, improved water quality, and created green jobs, while also attracting more than $1.7 million in private investment.

Focusing on high-end markets in large metropolitan areas could eventually help transform sanitation systems at scale

Acknowledgements

Authors Amaresh Belagal, Gayathri Muraleedharan, Shashank Palur, Shreya Nath

Editor Syed Saad Ahmed

Published by Nanditha Gogate

Follow us to stay updated about our work