Rural Futures

The Rural Futures programme seeks to transform rural lives and livelihoods by increasing farming incomes while restoring degraded land and water resources.

Context

Our Work

Publications

Context

Slightly over half of India’s farmlands have access to irrigation, with the rest depending on increasingly erratic rainfall. With groundwater levels declining in two-thirds of the country’s districts, expanding, or even sustaining, irrigation using dugwells or tubewells is a challenge. Irrigation through canals is an alternative, but they suffer from problems such as leakage and uneven distribution.

Moreover, incomes of rural residents, most of whom depend on farming and allied sectors for their livelihoods, are stagnating or falling. Crops like paddy and wheat offer better returns due to the government’s minimum support prices, but these are water-intensive and grown as large-scale monocultures. In contrast, crops like pulses, oilseeds, millets, etc. receive minimal or no support to become viable income sources for farmers. Besides, monocropping combined with the extensive use of pesticides and fertilisers can lead to land degradation, making agriculture unviable in the long run.

Thus, we need solutions that enable farmers to improve their incomes and also sustain water resources and ecosystems.

Our Work

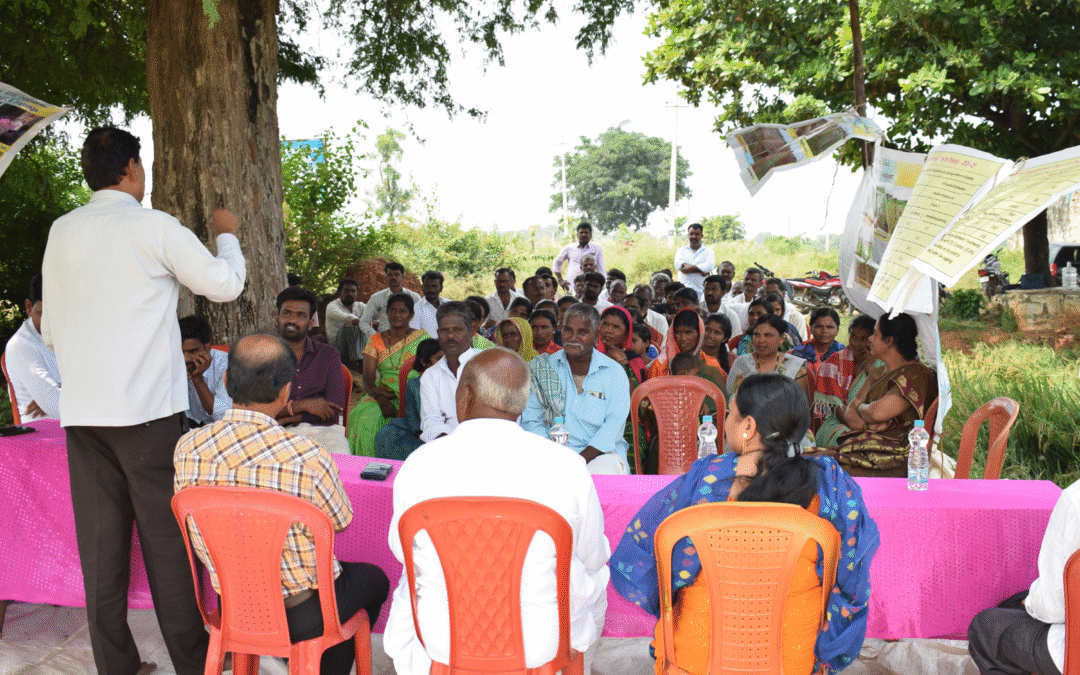

We are working in Raichur and Chikkaballapur districts of Karnataka, where we have set up transformation labs under the STEWARDS project. These labs are collaborative spaces where communities can co-develop pathways to sustainable, equitable transitions in water and agriculture to improve resilience in dryland regions.

Our partners include University College London; Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office; DCB Bank; Nvidia; IHE Delft; Prarambha; Advanced Centre for Integrated Water Resources Management; and SOIL Trust.

Our initiatives are:

1) Fostering water access and equity through better-governed irrigation in canal command areas.

Canal irrigation can help ensure that farmers have access to enough water during the Kharif season (June–October) and ample soil moisture for a second Rabi season (October–April) crop. However, it poses its own set of challenges. Canal systems are often poorly designed or maintained. On one hand, leakages due to evaporation, seepage, vegetation growth, wastage, etc. reduce the amount of water available for farmers. On the other, head-end farmers use most of the water, leaving little for tail-end farmers.

To ensure water access and equity, we are developing, implementing and socialising design principles for canal-water sharing in association with farmer water groups.

This initiative is being implemented in the parts of Raichur district that receive water from the Narayanpur Right Bank Canal.

A distributary of the Narayanpur Right Bank Canal in Raichur district, Karnataka

2) Promoting protective irrigation in dryland areas.

Rainfed farmers are facing erratic rainfall and long dry spells. Amid changing weather patterns, it is difficult to ensure yields in even one season, leading to losses. We are exploring options to promote protective irrigation using tank water, groundwater and soil moisture management in the drylands of Chikkaballapur and of Raichur, where canal water is not available.

*****

For both the above interventions, we are documenting marginalised communities’ needs and aspirations regarding water management. We shall use insights from this exercise to build their capacities through initiatives such as community hydrology programmes.

3) Piloting labour-saving technologies to enable diversified cropping.

Diversified cropping requires relatively fewer inputs like fertilisers, pesticides, etc. and also reduces the risk of crop failure. However, we have observed on the field that while monocropping systems have well-developed mechanisation techniques, this is not the case for diversified cropping. The tools tend to be rudimentary, the fields often require manual weeding and different crops have to be harvested at different times. Thus, diversified cropping is labour-intensive and women usually have to bear the burden.

To ensure that diversified cropping does not increase farmers’ burden, we are piloting labour-saving technologies (such as manual/electric weeders, EV tractors, harvesters and threshers for pulses, millets and oilseeds, transplanters, seed drills, etc.); training landless farmers to use these; and helping them become entrepreneurs.

Traditional diversified-cropping systems such as Akkadi Salu promote biodiversity and help farmers weather risks such as erratic rainfall, degrading soils and unpredictable markets

4) Facilitating market access to ensure farmers get good prices for their produce and grow diversified crops.

Farmers grow paddy because there is a ready market and a minimum support price offered by the government. Its cultivation ecosystem is well-developed — seeds, pesticides, machines, buyers etc. are in place — which other crops often lack.

Moreover, crops like millets, pulses, and oilseeds do not have an organised market, making it difficult for farmers to get minimum support prices or fair prices at local mandis (markets). Growing large amounts of a non-staple cash crop like chilli or cotton can also lead to a glut in the market and a sudden drop in prices.

We are mapping existing links to markets, barriers to increasing incomes, and current approaches to aggregation, value addition, and procurement contracts to develop and test strategies to improve farmers’ access to markets.

5) Researching the extent of land fragmentation and barriers to the better use of fallow land.

With increasing agrarian distress and aspirational migration to cities, a lot of rural land is left fallow. In some cases, the land has many owners or is locked in legal disputes and thus, there is no investment in land productivity or soil quality.

We are researching the barriers to the productive use of this land — such as concerns that the land could be usurped or the lack of enforceable contracts — and how these can be overcome.

Publications

When Good Farming Ideas Fail to Last

Improved agronomic practices often demonstrate clear results, but adoption fades the moment external support ends. Sustaining them requires rebuilding the larger ecosystem to both support and sustain the last-mile farmer.

From Fields of Struggle to Hubs of Innovation: Farmers, Mechanisation, and the Promise of Local Enterprise

A recent pilot across three villages in Raichur district demonstrates the power of local enterprise in advancing rural mechanisation. Farmers, women entrepreneurs, and rural youth are turning farm machinery into shared village resources through local service hubs, improving access to technology and strengthening livelihoods in the process.

Unpacking the Gender Gap in India’s Agricultural Tech Revolution

India's drive to integrate technology into agriculture promises innovation, ease, and greater rewards, but women farmers are often left behind. This analysis delves into the gender disparities shaping the future of agricultural technology in India.

Reimagining WUCS in Karnataka: Towards Inclusive and Sustainable Water Governance

A systematic, step-by-step approach is needed to build a strong, democratic WUCS from the inside out, shift the power dynamics, and give everyone a voice.

Promoting Equitable Irrigation, Market Access, Agricultural Innovation, and More | Insights from the Rural Futures Programme

The Rural Futures team shares what they learnt from their initiatives in Raichur, Koppal, and Chikkaballapur districts of Karnataka

Mapping Water, Building Ownership: A Ground-Up Approach to Water Governance

Introducing a tech component to participatory rural appraisal has changed how farmers engage with the process.

Raichur at the Crossroads: Gender-Sensitive Strategies for Sustainable Rural Labour

Published in The Federal

Crop Diversification: A Win-Win Approach for Farmers and the Environment

Crop diversification could be the key to economic and environmental resilience amid climate change and market volatility. Meet farmers from Chikkaballapur, Karnataka seeding a more sustainable future.

How Water Shapes the Lives of Farmers in Raichur: Field Notes from Mandalgudda

We’ve been researching land and livelihoods in Raichur over the past two years. The different strands of our analyses reinforced a known fact of life in the region – that water shapes decisions and livelihoods.

Field Notes from Raichur: Why MGNREGS Remains Key for Water Conservation in Rural India

Digging trench-cum-bund pits is a priority under the National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme, resulting in both livelihood and water security.

Addressing the Labour Barrier in the Transition to Crop Diversification

This study explores the labour dynamics of various crops, the gendered dimensions of farm work, and the technological interventions that can reduce the labour burden of diversified cropping and make it more accessible and sustainable.

Policy Brief: Augmenting Farmer Income With On-farm Carbon and Water Trade-offs

Agroecology has the potential to mitigate the adverse effects of unsustainable monoculture practices. However, it encounters barriers to widespread adoption, largely due to perceived short-term sacrifices against long-term benefits.

Raichur Roundtable: Equitable Water-Sharing for Sustainable Transitions in Agriculture

Along with the India Climate Collaborative, we convened a roundtable to bring together key stakeholders to discuss the future of water for transformation of agricultural landscapes.

What Does “Sustainable” Food Production around Bangalore Entail?

The agricultural landscape around Bangalore is experiencing environmental degradation – groundwater depletion, a decline in soil health and agrobiodiversity. Urbanisation and globalisation have changed the agricultural landscape as well as consumer preferences which in turn affect rural livelihoods and food production. This article explores the complexity of sustainable food production…

Using Systems Thinking to Create a Sustainable Food System

The agricultural landscape around Bangalore is experiencing environmental degradation – groundwater depletion, a decline in soil health and agrobiodiversity. Urbanisation and globalisation have changed the agricultural landscape as well as consumer preferences which in turn affect rural livelihoods and food production. This article explores the complexity of sustainable food production…

Tech is important, but trust is key when working with rural communities: Veena Srinivasan, Founder, WELL Labs

Published in indianexpress.com

Farmers in India Are Weary of Politicians’ Lackluster Response to Their Climate-Driven Water Crisis

Published in The Associated Press

Depleting groundwater: Why India needs to rethink many agri practices

Published in India Today

A 2,000-yo Irrigation System is Being Revived in North Karnataka

Published in Gaon Connection

70-80% Indian Farmers Depend on Groundwater; Solar Irrigation Inadequate to Change Crop Choices: Report

Published in Down To Earth