From Plural Livelihoods to Better Schools: What People Aspire for in Raichur

Field researchers in Raichur in August 2022, while planning for the rural aspirations study. Photo by Manjunatha G.

Mallana’s (name changed) family had separated when he was young, forcing him to abandon his education and look for work at a young age to maintain the home. Despite never completing school, he always harboured an ambition to secure a good, stable job, but the tide never turned in his favour. He told us that there are times when he is so frustrated that he ‘wished for a tsunami-like disaster to wipe them all away’.

He believes that his lack of education is the root cause of all his troubles, which is why one of his biggest priorities is to make sure his children are educated and go on to find government jobs. He also wants to be able to make a stable living through farming and build a home for his family. He splits his year between Bengaluru — where he works as a construction labourer — and his village of Mukkanal in Karnataka’s Raichur district — where he farms and also does work under the National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA).

In the nearby village of Chadakalgudda, six kilometres away, Yankamma (name changed) faces different but profoundly-difficult challenges. She belongs to an SC community, and talked to us about how rampant casteism is in the region, with people of her community not having access to land. She also talked about how a poorly-functioning MGNREGA programme depresses the prices of agricultural labour, forcing them to migrate to be able to earn just about enough to eat. She aspires to clear her debts and set up a small business, and wishes for greater unity in the village.

Villages in Raichur face land degradation and associated risks

These are just two brief anecdotes from interviews with 200 people under a comprehensive rural aspirations study that WELL Labs, along with Prarambha, our local partner, and Sarvodaya, an independent developmental organisation based in the neighbouring district of Koppal, are conducting in three villages in Raichur. This district is plagued by land degradation, threatening food and livelihood security. A large majority of this rural population belongs to the small and marginal category; they are even more vulnerable and prone to risks stemming from the degeneration of natural assets.

There’s a process of distress-driven diversification underway; and while a number of studies on ‘distress migration’ exist, only a few comprehensively document the aspirations of people in rural areas. A dearth of this kind of information may lead to an incongruence between the goals of ‘vision based’ development and the actual wants of people on the ground.

We have written about this larger context in a blog post published in August. And now, after months of fieldwork and interviews, we are able to share some early insights about this process and of patterns that are emerging of what people want to improve their well-being.

We adapted Kai Mausch’s rural aspirations framework

Under CSEI’s Farms and Forests initiative, we are working closely with local partners, such as Prarambha, and local communities to understand the drivers of land degradation and co-design restoration activities. We chose Sarvodaya, an independent research organisation based in the neighbouring district of Koppal to conduct the study. Insights from this study can shape the direction of land restoration and other possible interventions that CSEI-ATREE may facilitate, and may also serve as a model for similar studies.

Illustrations by Aditya Maruvada.

Mausch et al.’s study in rural Kenya adopted a narrative-based approach as opposed to hard quantitative methods to flesh out the nuances of aspirations and perceived opportunities. Our study follows this approach and tries to build on it by bolstering oral narratives with illustrations of current scenarios and future aspirations.

In line with Mausch’s framework, the aspirations study tries to map out the ‘livelihood strategy/portfolio’ for each of the 200 individual respondents across the three villages. This, the study has attempted to do by first capturing the current natural, social, physical, financial facets of their livelihoods.

We then used these responses as the foundation to map their aspirations, after which we charted out the strategies or opportunities they perceive are necessary in order to fulfil these aspirations.

How we selected villages, participants and trained enumerators

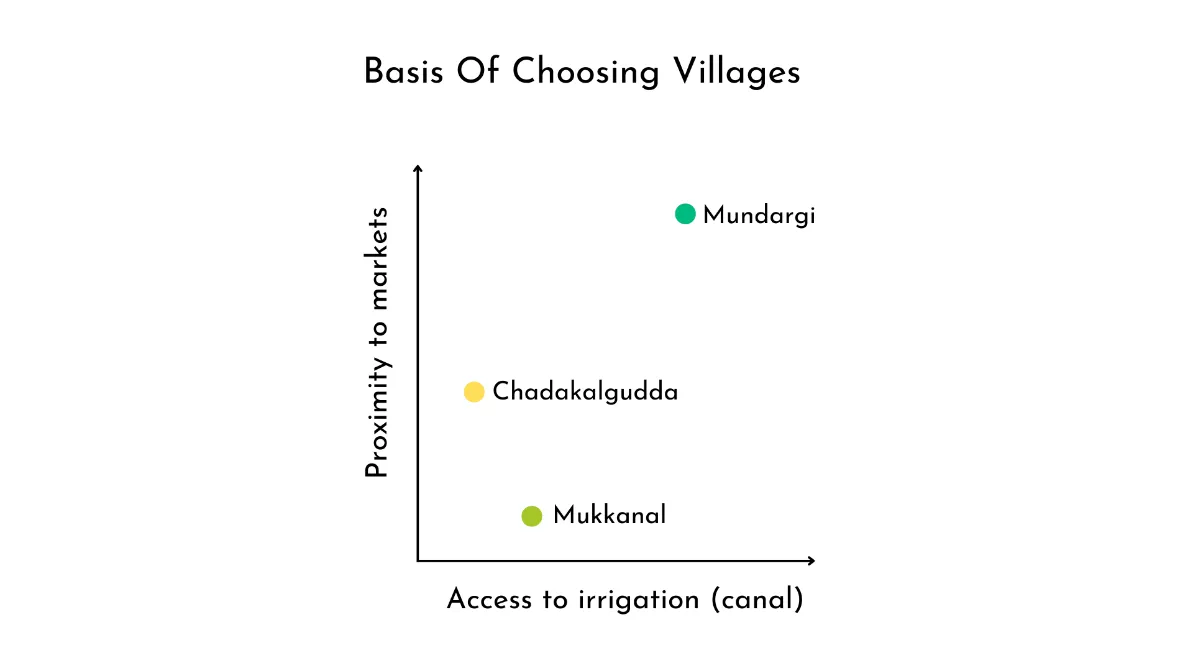

The study was conducted in three villages in Raichur district — Mukkanal, Chadakalgudda and Mundargi. The villages were chosen in consultation with Prarambha, our local partner who has been working to support vulnerable communities in different parts of Karnataka, including Raichur. The villages were selected primarily based on factors such as access to markets and access to irrigation, which Mausch et.al. also highlight as factors that play an important role in shaping aspirations.

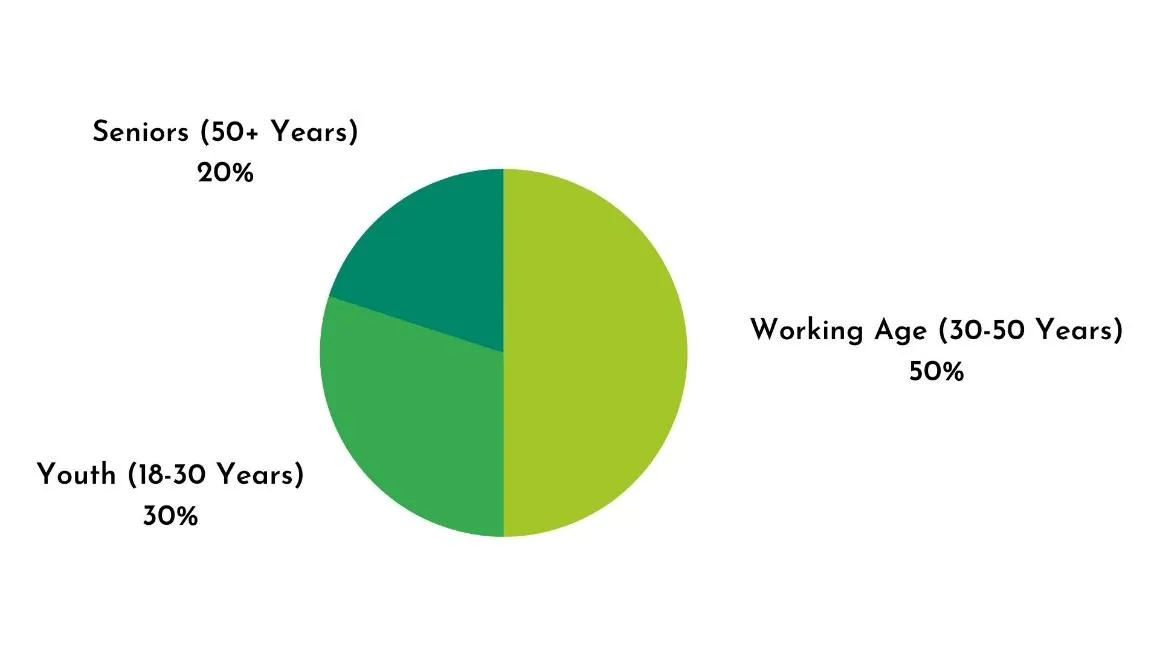

A total of 200 participants across the three villages were interviewed, with about 70 interviewed from each village. The participants were deliberately chosen based on their age, gender and economic status. We were careful to minimise the possibility of multiple participants from the same household (meaning under the same roof/sharing the same kitchen) participating in the study.

Those of working age (30–50 years) formed the highest proportion (50%) of participants interviewed, followed by youth (18–29) (30%) and seniors (50+) (20%). An equal number of men and women from the three villages were covered in the study.

Two teams of two enumerators each from Sarvodaya were formed to conduct the study. Multiple online and in-person training sessions were conducted with them to explain to them both the theoretical and practical aspects of the study while also covering important ethical protocols regarding data collection. The teams were frequently monitored to assess their progress and to keep abreast of and solve issues they were facing on the ground.

CSEI-ATREE and Prarambha carried out training sessions for enumerators with Sarvodaya on carrying out data collection.

Some early trends and insights

While a majority of the interviews have been transcribed, analysis of these interviews is underway. But there are a few early trends that have come up so far:

Rural aspirations are complex with each of the respondents laying out multiple aspirations for themselves and for their families.

Further, the nature of these aspirations differ based on age, gender and economic status. A single bad agricultural season, loss of a partner, debt, alcoholism and a plethora of other possible events have a significant impact on altering aspirations, highlighting internal and external risks associated with rural livelihoods.

A significant proportion of the participants in all the villages expressed a desire to either build a house or renovate existing tenements as an aspiration.

Educating their families (often children) also came across as a dominant aspiration. Life events like marriages are also important aspirational priorities as is the desire to rear animals, especially sheep. However, the qualitative nature of these aspirations may vary from village to village. While a demand for proper primary education was seen in Mukkanal, the respondents in Mundargi wished for their children to have access to secondary and tertiary education. Clearing existing debts is an aspiration most frequently expressed in Mukkanal.

The pathways to achieve these aspirations are also most often not linear, and involve a combination of strategies and adoption of plural livelihoods.

In a large majority of cases, NREGA, agricultural labour and animal husbandry form the bulk of the strategies to supplement income from farming. We also noted that where NREGA has not been functional, as in the case of Chadakalgudda, a greater number of respondents highlighted migration to cities as a pathway compared to respondents in other villages.

A majority of the respondents who migrated to cities (Bengaluru and Pune mainly) have had negative experiences.

They described the hard and often dangerous working conditions in cities and the lack of security and contrasted them with villages where they at least wouldn’t have to starve. However, in Chadakalgudda, where caste discrimination is rampant and the wages paid for agricultural labour are low (about Rs. 150/- per day), a significant number of respondents expressed a preference to continue to migrate.

Individual aspirations for the villages as a whole were also captured.

A majority of the respondents in all the three villages wished for better road and transport facilities. A desire for better educational facilities, better healthcare and better sanitation was expressed. A desire for agricultural input shops and better access to markets was expressed in Mundargi, the village with the better irrigation facilities of the three. A large majority of respondents from Mukkanal also expressed a desire for drinking water facilities, with some of them attributing the poor health of the villagers to a dearth of potable water.

Please note that our analysis is ongoing and we will soon put together a comprehensive report detailing our findings. This article documents only early observations and will be revised based on feedback and our improved understanding built through thorough analysis of all 200 interviews.

With inputs from Karishma Shelar

Edited by Kaavya Kumar

If you would like to collaborate, write to us. We would love to hear from you.

Follow us and stay updated about our work: