Part 2: Livelihood Lessons and Insights from Journey Mapping in Mukkanal

Livestock grazing in Mukkanal, Karnataka. Photo by Manjunatha G

In the first part of our blog series on the journey mapping exercise we conducted in Mukkanal village in Raichur district, we quoted Devappa, a farmer who says that the land here has been fallow for over two decades. This is an experience that many farmers based in this semi-arid region face, as this district has undergone severe degradation. There is an urgent need to carry out restoration work in dryland districts like Raichur, focusing on the livelihoods, needs and aspirations of small and marginal farmers like Devappa.

As we explained in the first blog, journey mapping is a qualitative research method that helps clarify how a person or community experiences a certain service or process; in this case, how farmers’ livelihoods are impacted by land degradation.

In this blog, we analyse our interviews with people from 17 different households within our pilot site of 27 hectares of agricultural land to derive five key points.

1. Current livelihood patterns:

The main source of livelihood for all 17 farmers is agriculture. The most common source of additional income is livestock rearing, followed by wages through NREGA (National Rural Employment Guarantee Act) and labour in other farms.

Migration is not a very common choice among these families, mainly because it is perceived as a difficult and unfamiliar way of life. People prefer livelihood choices that allow them to stay in the village.

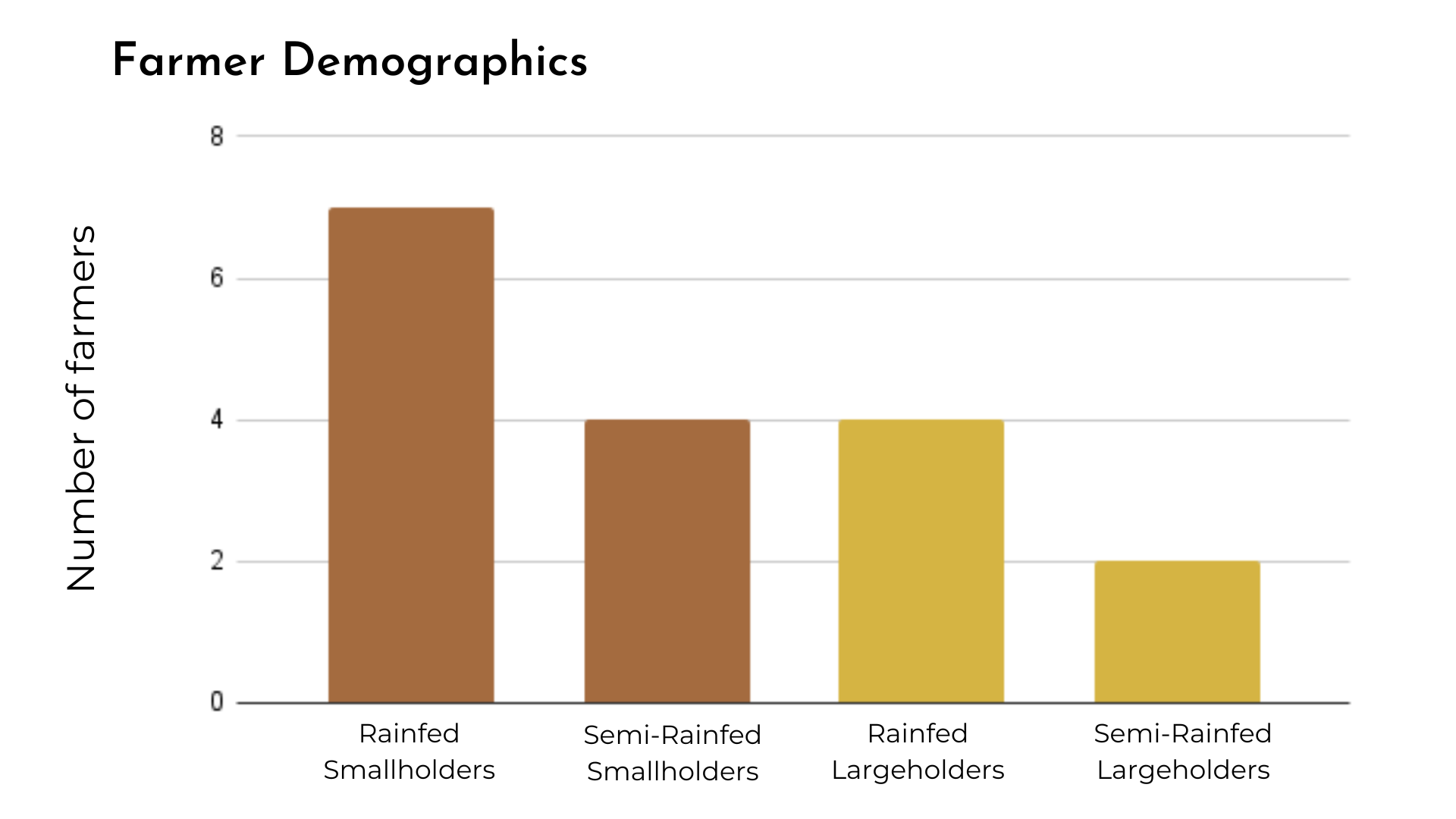

Majority of the farmers are smallholders with purely rainfed land. They grow crops twice a year, and cultivate some amount of fertile land in addition to the degraded land in our pilot site.

Demographics of the 17 farming households we interviewed

Also Read | Raichur Land Restoration Pilot: How We Studied the Local Context

The most commonly grown crops are cotton and pearl millet; cotton is grown only to be sold in the market and is a profitable crop for most. Pearl millet is grown partly for personal consumption (as it is consumed by both people and livestock) and partly to be sold in the market. Other commonly grown crops are paddy, redgram, chilli and groundnut.

Within agriculture, farmers spend the most on fertilisers, pesticides and labour. Among the crops grown, the highest expenditure is on chilli, which requires more fertilisers, pesticides and is labour intensive, followed by cotton, paddy and groundnut. The highest per acre income and profit is derived from chilli, followed by cotton.

2. Major challenges:

Due to a combination of high input costs, low yields and low market prices, many farmers are not able to make a profit from agriculture. These losses have been exacerbated by unpredictable rainfall in the past few years, which has caused extensive crop damage, especially to cotton.

Further, farmers are not receiving any government insurance, despite having paid for it, to mitigate these crop losses.

Many farmers also report that the introduction of irrigation two decades ago changed the characteristics of the land and made it infeasible to cultivate crops such as groundnut, redgram, greengram and sunflower. In some cases, over-irrigation spoilt the soil and made it difficult to cultivate anything at all, and in others, it also caused diseases and pest infestations for certain crops. The introduction of irrigation thus catalysed the shift to chemical-based fertilisers and pesticides, as people began using them both to counter diseases and bolster the increase in productivity and yield that irrigation had initiated. However, these inputs have further deteriorated the quality of land.

Chillies and cotton are some of the key crops in Mukkanal. Photo by Manjunatha G

3. The impact of land degradation:

Out of the 17 households who cultivate the land in our pilot site, 10 households also own or lease other land in the village, which is more fertile. This provided us with a valuable opportunity to assess the differences in expenditure, income and profits between cultivating fertile land and degraded land.

When we compared the average per-acre expenditure on each crop, we found that farmers who cultivate fertile land spend less than those tilling degraded land for all crops except for cotton.. This could be due to the fact that cotton grows well on saline soil, hence farmers who grow it in the highly saline land in our pilot site do not have to add as many inputs to make the soil suitable.

In terms of average per-acre profits, we compared both two types of land to find, predictably, that profits were far higher from fertile land, where the yield was higher for all six crops grown in the region (mentioned under the first section above). Farmers were not able to cultivate chilli and groundnut at all in the degraded plots.

These results clearly demonstrate that improving the fertility of the land will have a concrete impact on people’s yields, income and profit from agriculture.

4. The impact of irrigation and landholding size:

Households that practise purely rainfed agriculture earn less than semi-rainfed farming households that harness water from sources such as streams and lakes. Rainfed farmers only earn a profit for cotton and pearl millet. For all other crops, they either barely break even, or face heavy losses. Semi-rainfed farmers also receive better yield for all crops apart from pearl millet.

This stark difference points to the importance of harnessing additional sources of irrigation, apart from rain.

There also exists a correlation between landholding size and access to fertile land, as five out of six large landholders (households with over five acres of land) have some amount of fertile land that they cultivate. This indicates that smallholders are more likely to be incentivised to participate in restoration activities, as they are less likely to have fertile land to cultivate as an alternative.

Discussion with Prarambha field staff on methods and results of the journey mapping exercise. Photo by the Prarambha team

5. Livelihood diversification:

An intriguing learning from journey mapping is that many families earn very little from agriculture, but only some of them have chosen to diversify their sources of livelihood. Interestingly, the households that are facing outright losses from agriculture have not diversified to non-farm incomes at all. In some of these cases, it is because the family members are old and are not able to work as much, while in other cases, people simply do not have the time or resources to diversify livelihood activities.

Livelihood diversification has great potential for increasing overall income for families; those who have diversified have earned double and even quadruple of the income they earn from agriculture, through other sources such as livestock rearing, NREGA, agricultural labour and migration.

A farmer with his goats in Mukkanal. Photo by Manjunatha G

For Devappa and other farmers here, the journey mapping exercise was a means to identify the root causes of their mounting losses and dropping yields. It also clarified pathways to mitigate these issues.

It was clear from our analysis that efforts to address land degradation must consider a range of interventions. For one, it is necessary to amend cropping, land preparation and fertiliser practices in ways that revive degrading soils and not further deteriorate it. It is also important to explore how some form of irrigation can be provided to farmers who are currently purely rainfed so that they can improve the productivity of their land. Diversifying sources of income is another key area as households that have multiple streams of revenue were found to be less vulnerable than those who only rely on agriculture.

Top-down planning and implementation of solutions could make a bad situation worse. Methods like this help tailor interventions to the unique needs of farmers like Devappa, thereby securing the future of their land and their livelihoods.

Credits

The author conducted this work when she was with the Centre for Social and Environmental Innovation at the Ashoka Trust for Research in Ecology and the Environment (CSEI-ATREE). WELL Labs is now taking it forward in collaboration with ATREE.

Edited by Meghna Majumdar and Kaavya Kumar

If you would like to collaborate with us outside of this project or position, write to us. We would love to hear from you.

Follow us and stay updated about our work: