Bengaluru’s Wastewater Market Experiment: A Promising Solution for Water-Scarce Cities Globally

Bengaluru, India’s Silicon Valley, adds another layer of innovation to its belt and is emerging as a leader in wastewater reuse. As the city has been in the throes of its most severe water crises to date, the city’s residents, firms, experts, utilities and regulatory authorities have been vying for innovative solutions.

A study by WELL Labs reveals boosting treated wastewater reuse as a solution with very high potential in terms of offsetting freshwater use and building water security. The question is: what is the right approach to reusing wastewater?

In order to answer that, let’s start with how the city’s water flows.

Bengaluru acts almost like the state’s kidneys. The Cauvery river is the main source of municipal supply for the city. This has been a source of contention in the past, with rural areas resenting Bengaluru getting prioritised especially during droughts. Many of the surrounding agricultural districts, which are the state capital’s food baskets, are parched. In recent years, Bengaluru’s wastewater is being sent to peri-urban areas where it’s being reused for agriculture and industry. Although this wastewater transfer has its own challenges, given these areas’ current predicament, this wastewater is a lifeline.

Further, Bengaluru is a rare city that’s at the top of a plateau. Freshwater is pumped 350 metres uphill and across a distance of over 90 kilometres from the Cauvery river at great expense. Treating and reusing wastewater makes sense from a carbon footprint/energy costs perspective as well. But with scarcity predominantly affecting the densely-populated groundwater-dependent suburbs of the city, which still don’t have municipal water supply and sewerage networks, the logistics of wastewater reuse is complicated.

Instead, a promising and often under-valued solution is harnessing the full potential of the ~2,500 on-site Sewage Treatment Plants (STPs) already installed at apartment complexes.

Bengaluru has adopted a unique decentralised approach to managing its wastewater. While most of the world has their wastewater run through pipes connected to centralised STPs run by the government, nearly 25% of Bengaluru’s sewage is managed by residents on a small-scale through on-site STPs .

This was a result of a 2016 regulation by the state pollution control board as a response to a National Green Tribunal (NGT) order to address pollution of lakes; the city’s explosive growth coupled with the lack of sewerage, meant that most new apartment complexes were discharging raw sewage into the city’s stormwater drains. The regulations mandated apartment complexes above 50 units, and commercial and institutional buildings with more than 2,000 sq m to have an STP on site.

As a result, out of the 1,940 MLD of wastewater produced daily in the city, 640 MLD can be treated in decentralised STPs. It is estimated that apartments alone have the capacity to treat up to 500 MLD, which could potentially take care of 25% of the city’s sewage.

However, the actual amount of treatment in apartments lags at 340 MLD; in practice, many of these systems are not operated or maintained properly resulting in a high rate of malfunctions.

The key reason for this was that residents simply did not have the incentive to spend high charges to maintain these systems; there was no economic case for wastewater treatment. Wastewater treatment is expensive and can make financial sense if the resultant wastewater is valued. But the domestic freshwater is so heavily subsidised that it makes the economic case for on-site sewage treatment weak.

However, the recent water crisis coupled with the new policy has changed that.

A recent directive from the Karnataka government allows the sale of 50% of the treated wastewater from apartments for non-potable uses, creating a wastewater market that could potentially meet 26% of the city’s water demand.

The water crisis has led to most on-site borewells running dry leaving residents, builders and industries mostly reliant on tankers. As a result, tanker water prices have skyrocketed and gone from Rs. 60-90/kilolitre (kL) to as high as Rs. 200/kL. Treated wastewater is being sold at Rs. 10-80 Rs/kL, depending on quality, making it competitively priced and building an economic case for wastewater treatment and reuse, turning onsite STPs into an asset rather than a liability.

Prior to this ruling, the regulation as it stood, required apartments to comply with zero liquid discharge (ZLD); this meant apartments had to not only treat wastewater to standard but also reuse every drop within their premises. Most STPs did not function well enough for the treated wastewater to be used for anything beyond gardening or in better run plants, toilet flushing. As a result, many apartments were left with excess treated wastewater that they had to discharge to drains – punishable by a fine.

Read | How We Can Make Bengaluru’s Water Systems More Sustainable and Affordable

What makes this policy relevant beyond the current crisis is that groundwater for commercial uses like construction has now also been banned. As a result, the water for these uses is not only permanently high-priced, but also hard to acquire. Construction alone accounts for over 15% of the water demand during the dry season, making it one of the most interesting use cases for treated wastewater.

If we were to put different reuse options together, how much freshwater could we potentially save?

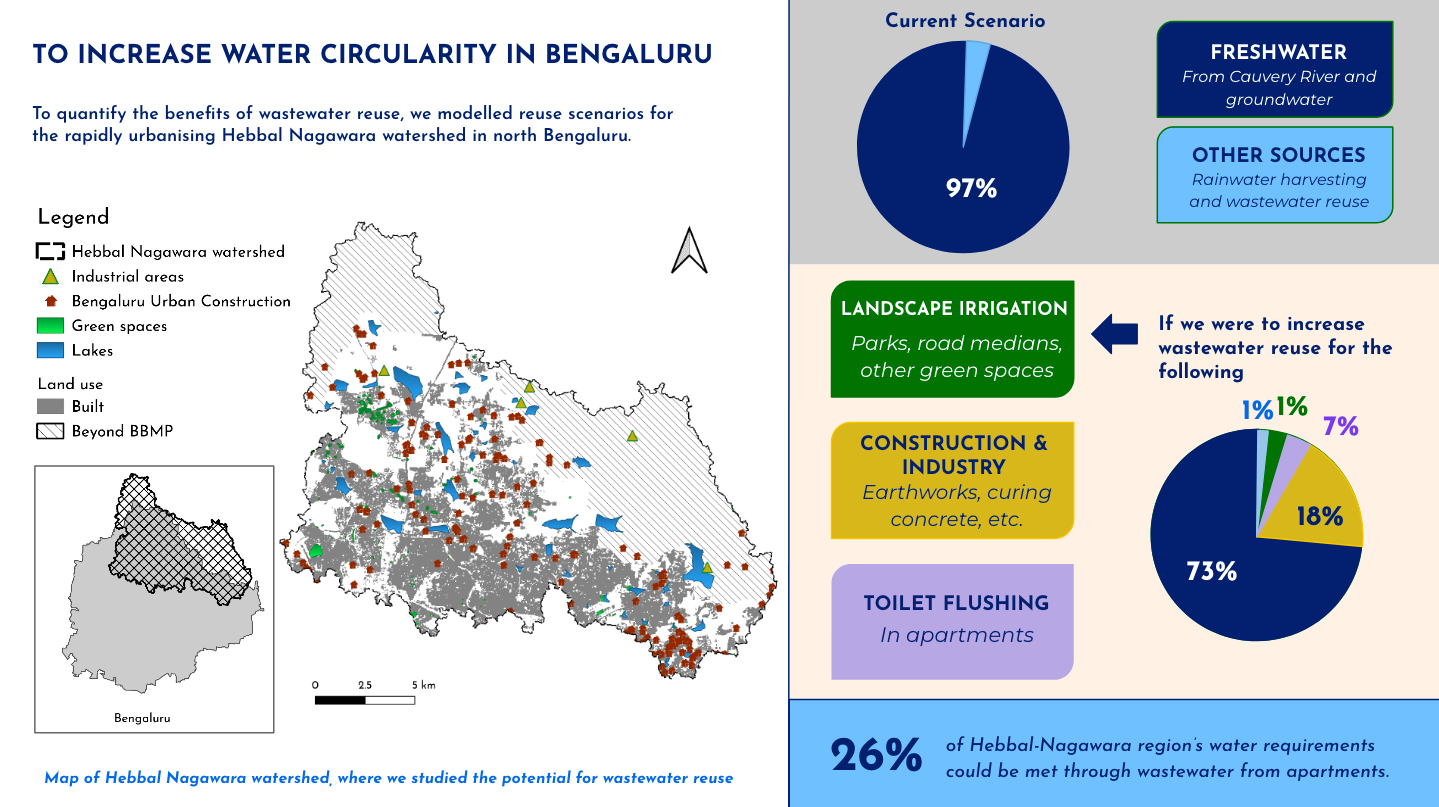

At WELL Labs, we modelled what this could look like for the Hebbal Nagawara watershed in north Bengaluru. Based on the number of apartments, industrial areas and construction sites, we calculated that around a quarter of the water demand in the area could be met through reclaimed wastewater sourced from decentralised STPs. The infographic below shows the break up:

The Hebbal Nagawara watershed is a rapidly-urbanising part of the city and thus makes for a good case study for us to model wastewater reuse potential.

More safe onsite reuse is a long-term co-benefit of this market.

If there is any silver lining to the current water crisis, it is that apartment residents are now very aware they need to conserve precious groundwater and reuse as much treated wastewater as possible. For years, reusing wastewater from their STPs for uses other than toilet flushing and landscaping has not happened mainly because of a stigma associated with wastewater. In the current crisis, their STPs provide a much needed, drought-resistant source of water. Moreover, the legalised market for offsite reuse creates additional economic incentives for upgrading malfunctioning STPs.

Subsequently, the benefits of having a well-functioning and high-quality STP onsite are now increasingly visible in RWAs across the city. A few apartments decided to upgrade their systems and sell their excess treated wastewater for commercial customers in the neighbourhood even before this mandate. During the crisis, many of them reported that they stopped the sale of treated wastewater and began using the water on-site.

In the long run, more on-site reuse should be enabled by the upgradation of systems — a necessary step that will be catalysed by the economic incentives linked to selling the water for off-site reuse . On-site reuse will increase circularity and prevent inefficient and carbon-intensive water transportation via tankers.

This could scale beyond Bengaluru.

Bengaluru’s urbanisation story is not unique, most developing cities across the globe struggle with building water and sanitation infrastructure in the context of explosive urban growth. When it comes to treating sewage, nearly 75% of the cost can be attributed to the piped sewer network. In other words, transporting sewage is almost three times more expensive than treating it. Therefore, removing transportation from the equation could potentially save a lot of money – we will explore this in more detail in a separate blog.

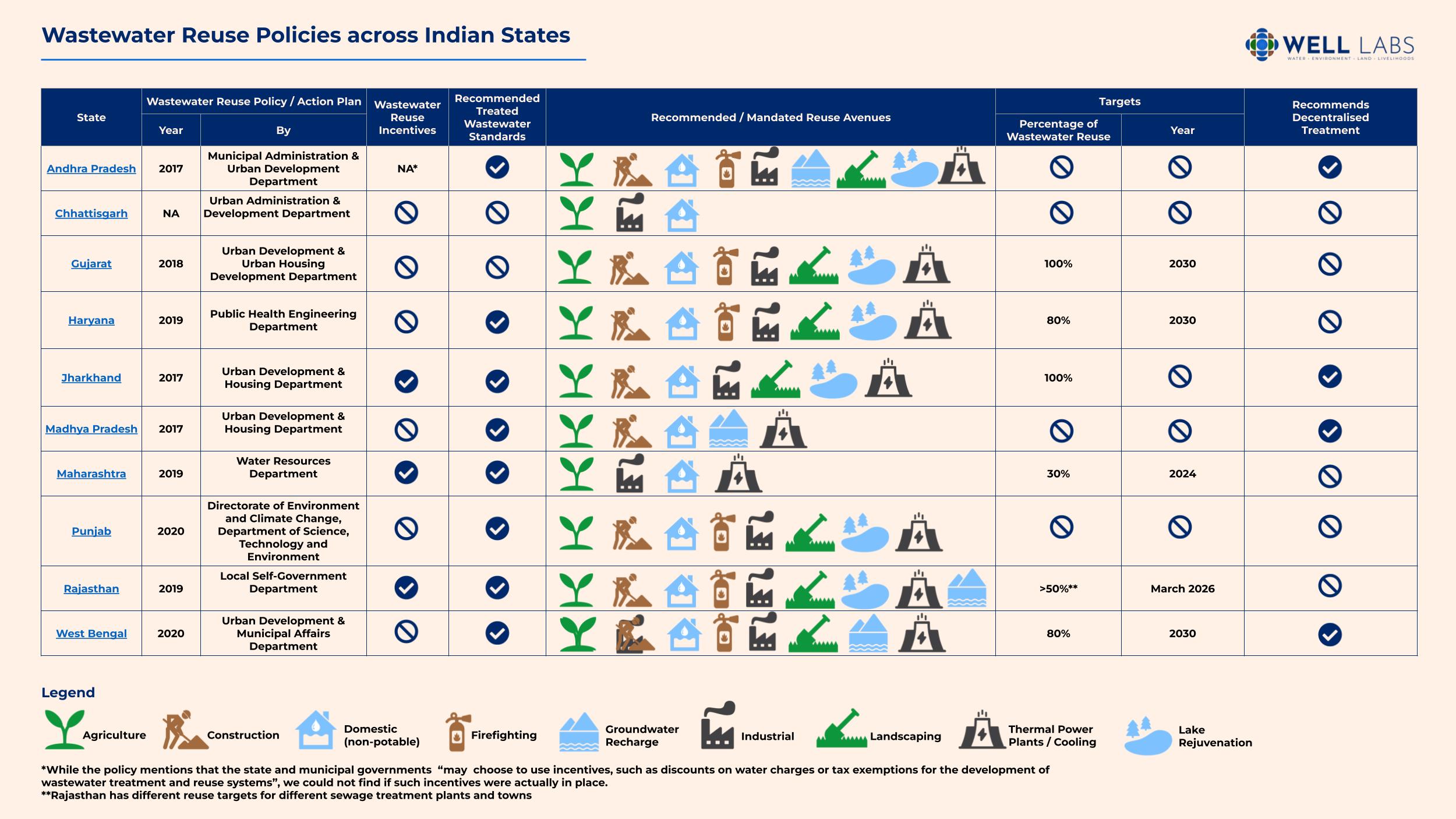

Wastewater reuse policies, targets, and recommendations for various Indian states. Read more here.

Utilities in different parts of the world are struggling to provide continuous supply with unpredictable rainfall patterns that can be linked to the changing climate. Bengaluru is paving the way to test whether selling outside the fence can be the impetus needed to eventually boost reuse within the fence.

In the short and medium term, when reuse outside the fence is the focus, safety and quality of water is methodically monitored and ensured for the experiment’s success. This could mainstream a system of best practices in terms of monitoring and safety protocols that would build trust in the treated water and convince people to make more use of it.

Ensuring safe reuse, however, is pivotal to the success of this innovative approach

Decentralising wastewater treatment reduces the cost of sewage transportation and increases opportunities for circularity. Ensuring safety will require a whole series of regulatory, operational and technological innovations.

In part 2 of this series, we will discuss what steps need to be taken in order to make sure that wastewater is being reused safely to create win-wins for the environment, residents and businesses.

We are working on standard protocols for safe reuse along with innovative business and transportation models in collaboration with Swiss Federal Aquatic Institute of Science and Technology (EAWAG), Bangalore Apartments Federation (BAF), Confederation of Real Estate Developers’ Associations of India (CREDAI), Urban Local Bodies and water utilities in Bengaluru.

If you are interested to learn more, please contact us here. Read more about our learnings so far from the Water Reuse Project here.

With inputs from Veena Srinivasan, Cheshta Rajora and Shashank Palur

Visualisations by Saad Ahmed and Sarayu Neelakantan

Edited by Kaavya Kumar

If you would like to collaborate, write to us. We would love to hear from you.

Follow us and stay updated about our work: