Bengaluru Has the Highest Number of Decentralised Sewage Treatment Plants Globally. Are They Effective?

Bengaluru, Karnataka. Credit: Sanket Shah, Unsplash

Bengaluru generates enough wastewater a day to fill over 750 Olympic-size swimming pools a day. This is more than the amount of water it draws from the ground or the Kaveri river. However, the city’s water supply and sewage system is concentrated in the central, older parts — it often does not cover the rapidly growing suburbs with higher population densities.

To overcome this gap, the city mandated that residential and commercial buildings above a certain area install on-site decentralised sewage treatment plants (STPs). The city now has the largest number of decentralised STPs globally: about 2,700.

But what is the quality of the treated water and cost of treatment? In the absence of a full-fledged sewerage system, what do apartments do with the water? What are the challenges of operating decentralised treatment plants and how can we overcome them?

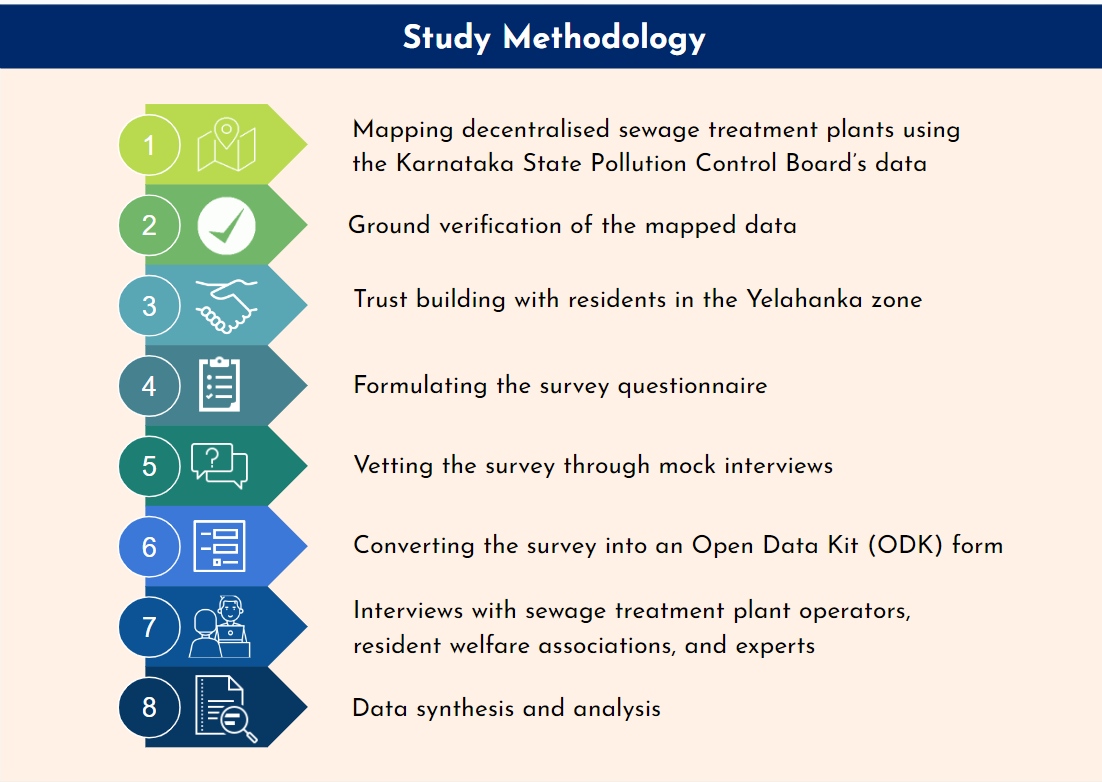

To explore answers to these questions, we conducted a study with Resident Welfare Association members, STP operators, and residents of 58 apartments.

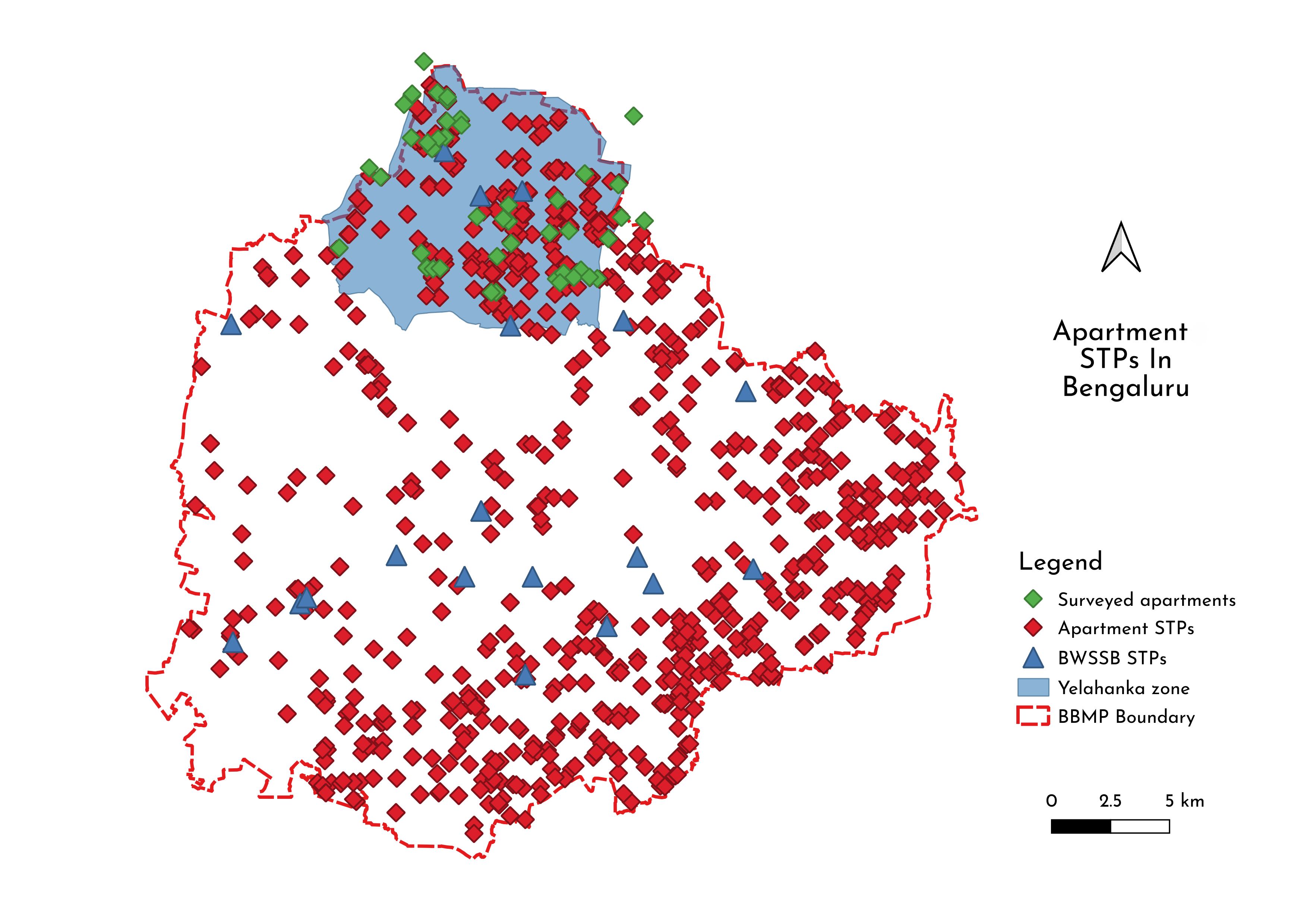

The study site was Yelahanka zone, a predominantly residential region in northern Bengaluru, and its timeline was August 2023 to February 2024. We selected Yelahanka as it is slated for significant development under the city’s 2031 Master Plan. This makes it ideal to explore and implement innovative decentralised wastewater management solutions. The zone has 174 decentralised STPs and many more are in the pipeline.

Our survey included questions around:

1. Apartment configuration and demography

2. STP design, technology, capacity, operating procedure, and cost

3. Reuse of treated wastewater on-site in apartments and the quantity of surplus wastewater

4. Perceptions of STPs, treated wastewater, and wastewater reuse

Findings

1. The Karnataka State Pollution Control Board (KSPCB) has approved 325 STPs in the Yelahanka zone, but only half have been built.

The KSPCB has a database documenting entities that have received environmental clearance to operate an STP. However, this register lacks geographic coordinates, which makes accurate mapping a challenge.

Through on-ground verification — physical visits and neighbourhood enquiries — we found that only 174 of the 325 registered decentralised STPs in apartments were constructed and functioning.

Map of decentralised sewage treatment plants in apartments in the Yelahanka zone, Bengaluru. The green dots show the apartments we surveyed. Credit: Shashank Palur.

2. Three-fourths of the surveyed apartments used the Sequence Batch Reactor (SBR) technology, popular for its efficiency and reliability.

However, we observed a lack of advanced treatment technologies, such as membrane bioreactors, as they can be expensive. Apartments with efficient STPs and tertiary treatment systems were more likely to reuse treated wastewater for diverse purposes.

Read More | Grey to Blue: What Can Bengaluru Learn From Chennai on Tertiary Treatment of Wastewater

3. Many Resident Welfare Associations do not have the capacity to operate STPs.

Builders hand over STPs to Resident Welfare Associations about 3-5 years after the apartment’s construction. The associations, in turn, rely on STP operators to run and maintain their plants. Most operators only have a school education and learn on the job. They rely on their experience to handle any day-to-day issues that may arise. However, they cannot resolve many problems as they lack technical skills (A builder we talked to for the study compared an STP’s complexity to that of the human body). In some small apartments, security guards double up as STP operators, with STP consultants chipping in when problems occur.

Our surveys highlighted the need for technically trained operators who can identify the source of a problem and find solutions in the absence of standardised operating procedures for these plants. There should also be regular audits by a third party to ensure STPs function optimally.

4. There is a huge disparity in operational costs between small and large STPs.

Plants with capacities below 80 kilolitres per day are prohibitively expensive to operate, making decentralised treatment less viable for smaller apartment complexes. Larger STPs, with capacities above 100 kilolitres a day, are more cost-effective since economies of scale help spread out fixed costs, such as STP operators’ salaries, and reduce the fee each household in the building has to pay.

5. The quality of treated wastewater varied significantly across the surveyed STPs.

We identified the following reasons for subpar water quality:

- Differing operational practices, such as turning off pumps and blowers to reduce noise at night.

- Replacing electro-mechanical components in old STPs is expensive, so many apartments do not optimally maintain their plants.

- Improper STP design (for example, small-sized tanks due to space constraints).

- Inadequate aeration practices, especially during power cuts, when apartments rely on costly diesel generators.

Most of the apartments we surveyed test total dissolved solids (TDS), pH, and chlorine levels, but not parameters like faecal coliform levels. The unavailability of testing kits recognised by the Karnataka State Pollution Control Board and inadequate testing protocols make it difficult to test the water quality on-site.

Most apartments meet basic water quality standards for non-potable reuse, such as toilet flushing and landscaping, but fail to meet the higher water quality standards required for agriculture or industries. However, only 13% of the surveyed apartments wanted to upgrade their STPs to improve water quality.

6. While some residents viewed STPs as essential infrastructure for environmental protection, others considered them burdensome and costly.

Most resident welfare association members did not have an in-depth knowledge of STP operations. Targeted education and awareness campaigns could help them better understand the intricacies of and need for sewage treatment.

7. Three-fourths of the freshwater used by the surveyed apartments came from borewells; a third of the apartments relied solely on groundwater.

This dependency on groundwater is unsustainable since it is ‘over-exploited’ across the city, that is, the extraction rate is significantly higher than the recharge rate. About half of the city’s borewells have dried up. As groundwater becomes scarce, apartments are increasingly relying on water from tanker trucks, which can be prohibitively expensive.

8. Almost 60% of excess treated wastewater goes unused and often pollutes water bodies.

Apartments reuse some of the treated wastewater for toilet flushing and landscaping. While the law does not allow apartments to discard the excess wastewater, most release them into stormwater drains or empty plots as they have a huge surplus they cannot use. As a result, 60% of the treated wastewater literally goes down the drain!

A decentralised sewage treatment plant we surveyed in the Yelahanka zone. Credit: Hari Prasad H.K.

Limitations

1. These insights are specific to the Yelahanka Zone and might not apply to other parts of Bengaluru.

The urban development patterns and infrastructure in Yelahanka differ from that of other zones, which may have different population densities and wastewater treatment techniques. Therefore, the findings and recommendations might not be equally applicable to all parts of Bengaluru.

2. We encountered challenges in getting accurate data.

Most apartments did not have separate electricity meters connected to their STPs and some did not share payment receipts to maintain the privacy of their records. In a couple of instances, there were discrepancies between the Resident Welfare Association’s data and the STP operator’s records. We were unable to resolve some of these discrepancies as the relevant stakeholders were not available.

Therefore, we gauged the costs of running STPs and their energy consumption through a literature review of compliance reports that apartments submit every five years to KSPCB to obtain an operation certificate. We also talked to STP vendors to get estimates regarding the capital and operating costs of different kinds of STPs.

It was difficult to test the water quality as apartments wanted to keep the data confidential. We made assumptions regarding water quality based on physical characteristics (smell, colour, turbidity, etc.) and how apartments currently reuse the treated water.

*****

Regardless of these limitations, our study reinforced the immense scope to boost wastewater reuse in Bengaluru by improving the treated water quality and building wastewater markets.

In this regard, the Government of Karnataka’s directive allowing apartments to sell up to 50% of treated wastewater from their STPs for non-potable purposes is a gamechanger. If properly managed and regulated, apartments can sell the excess treated water for industrial use, construction, or irrigation, turning a waste product into a valuable resource. The money generated from the sale of wastewater can also be an incentive for apartments to maintain and upgrade their STPs.

During the study, we also came across apartments keen on retrofitting their STPs to enable them to do tertiary treatment. This will allow for the increased use of treated water for non-potable purposes and thus, improve freshwater savings. In the long run, this could significantly reduce groundwater extraction and the city’s reliance on water from the Kaveri river.

Authored by Hari Prasad H.K, Shashank Palur, Sneha Singh, Shreya Nath

Edited by Anika Choudhary and Syed Saad Ahmed

Published by Anika Choudhary

If you would like to collaborate, write to us. We would love to hear from you.

Follow us and stay updated about our work: