Setting the Context — Water Governance in Bengaluru

Cities are shaped by their water resources. Think of coastal cities that have evolved to become important trade centres, such as Mumbai and Cochin. There are riverine cities too. Many were capitals of past empires, such as Agra and Tanjore. A third typology of cities have materialised around lake systems — Bengaluru, Udaipur and Jalgaon are known examples.

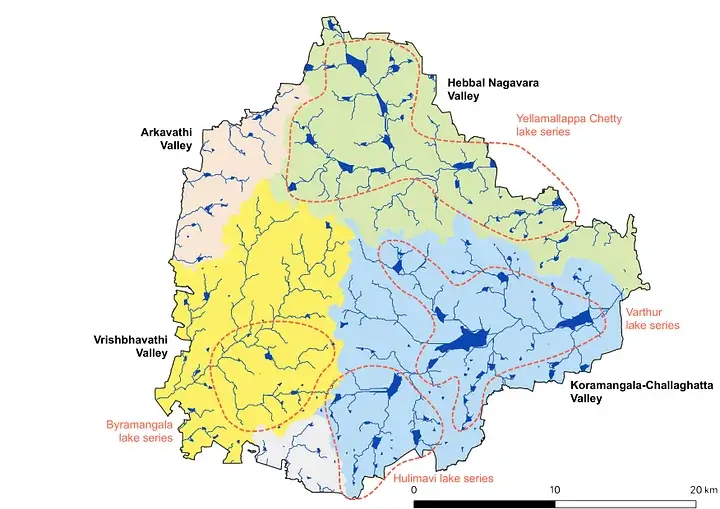

Before the era of piped water supply, Bengaluru’s lake system, dating back to at least the 6th century CE, was central to its domestic and economic growth. Past rulers, landowners and local chieftains invested to expand and maintain lake infrastructure. But today, the water sector in Bengaluru is governed by a network of institutions focusing on different jurisdictions and carrying out different functions.

Without a single agency to coordinate work and ensure water is managed holistically, the city suffers, apparent from the recent floods and water pollution.

In this blog, we provide an overview of how Bengaluru’s institutional structure in the water sector has come to be so complex today. We also describe how other cities have dealt with fragmentation in water governance.

Read | Part 1: Why We Need Urban Water Balances

Despite centuries of effort that went into building Bengaluru’s water resilience, lakes eventually began to lose their importance with the introduction of piped water supply around the 19th century. It also marked a shift in the approach to urban water governance.

Earlier, the cascading lake system required decentralised management based on traditional knowledge. These common pool resources remained crucial in city planning as livelihoods were directly dependent on them. Piped water supply brought a shift towards centralised technocratic governance. Decision-making in Bengaluru’s water sector became a complex and time-consuming process, with the involvement of many governing bodies such as the Government of Mysore, Municipalities of the City, the Military department and the Engineering Department of the Government of India — and this was a century ago.

Water governance in Bengaluru today

Today, the network of government and non-government actors shaping the city’s water has grown in complexity. Even so, managing water in a rapidly expanding city is no easy task.

To begin with, the city’s limits are hard to define, simply because it keeps changing over time. To keep up, institutions and their jurisdictional responsibilities also need to expand and evolve. Several jurisdictions in and around Bengaluru have been created in order to manage urban development along with the larger region that the city depends on and influences. How different institutions (focusing on different jurisdictions) coordinate with each other is particularly important in water governance, because water moves across boundaries — be it groundwater, rivers or lake systems.

Read | Part 2: Where Does All The Water Go? The Sankey Diagram as an Effective Visual Tool

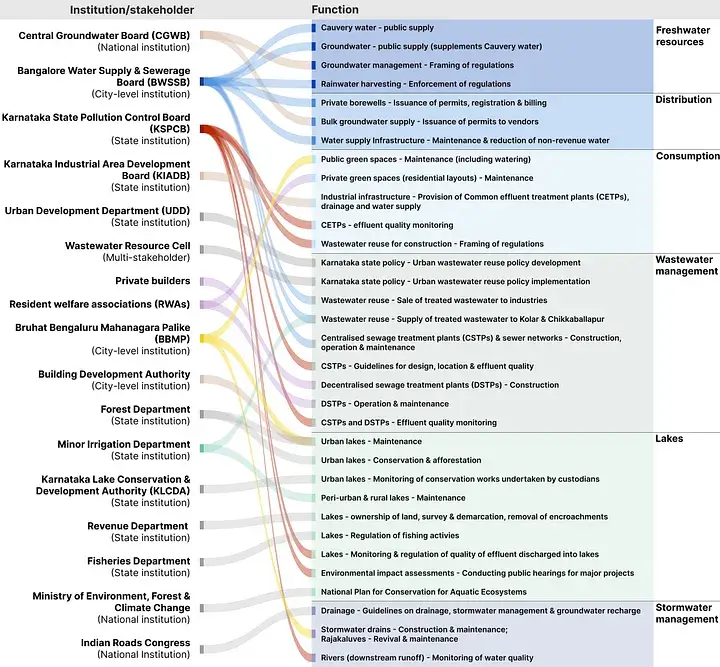

In addition to jurisdictional responsibilities, government agencies also oversee different functions/components of the urban water system. Very often, each of the functions is within the purview of local, state level and national institutions. While national and state level institutions typically develop policies and regulatory frameworks, local bodies have a more operational role.

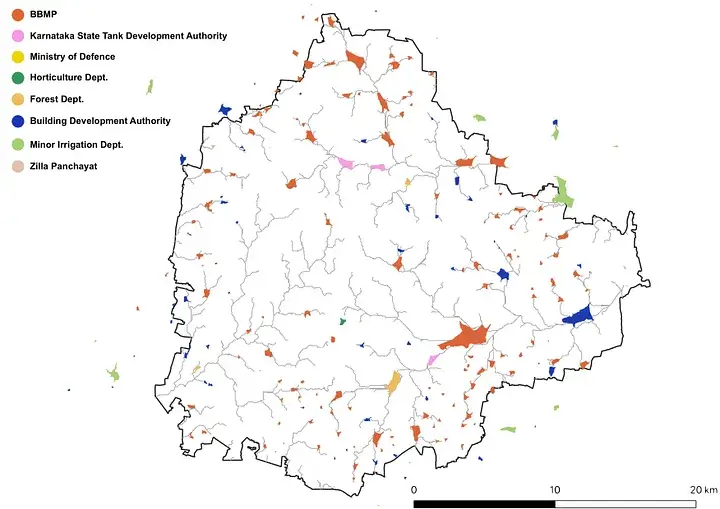

Allocating responsibilities are not necessarily straightforward, especially when multiple institutions stand to benefit from a shared resource.

Take, for example, the arrangement between the Bengaluru Water Supply and Sewerage Board (BWSSB), Chikkaballapur and Kolar districts to manage wastewater. The agreement between these institutions is that treated wastewater from Bengaluru is to be used to rejuvenate lakes in Chikkaballapur and Kolar. The BWSSB is responsible for building and managing wastewater treatment plants, whereas the Minor Irrigation Department (MID) manages rural lakes and ensures water supply for agricultural use. Challenges arose in the project’s financial management. Should BWSSB fund the project entirely through its revenue from sewerage charges and wastewater sales to industries? Or should MID also contribute financially? BWSSB is a city-level institution and MID is a state-level institution. Which institutions should be responsible for resolving such conflicts? These are the kind of questions that arise when institutions have to work together to manage a common resource.

Figure 2 lists the various institutions and their functions in the water sector in Bengaluru. Despite the diversity of institutions and functions, the city suffers without a single institution bearing the responsibility of holistically managing its water.

How are other cities working towards coordinated governance?

The issue of fragmentation in urban water governance is not unique to Bengaluru. Globally, cities are taking an active effort in increasing coordination between different government departments through nodal agencies. The Metropolitan Glasgow Strategic Drainage Partnership, for example, is a non-statutory collaboration of multiple public agencies from the water, environment and urban planning sectors. The partnership assists the Scottish government in developing long-term strategies in integrated flood risk management. Singapore’s Public Utility Board is another good case study of a coordinating agency that oversees all components of the water system — from supply and sewerage to management of water catchment and coastal zones.

Melbourne’s water utility took a rather creative approach. They designed an interactive tool based on a model of their urban infrastructure system. The tool creates future scenarios of how the city’s water infrastructure would perform in a variety of situations given specific conditions of population, climate change and water management strategies. The broader aim of the tool is to enable government and non-government actors to collaboratively ensure Melbourne’s long-term water security.

But, the cases of Melbourne, Singapore and Glasgow are those in which local governments have greater monitoring capacity and regulatory control than in most Asian cities. Jakarta adopted a more bottom-up approach. They developed a tool for urban disaster-risk management that facilitates crowd-sourced disaster reporting through social media, but the information is validated by government authorities. The platform is an example of how planning and disaster response can be shaped by informal information sourced from local communities as well as formal information from government agencies.

In the four cities, different strategies were used to increase engagement and coordination between actors. However, a common criteria for effective coordination and shared decision-making is the availability of data.

Stay tuned for our next set of blogs in the series that explain how we gathered data on Bengaluru’s water system.

Credits

This work was conducted by the authors when they were with the Centre for Social and Environmental Innovation at the Ashoka Trust for Research in Ecology and the Environment (CSEI-ATREE). The work is now being taken forward by WELL Labs in collaboration with ATREE.

If you would like to collaborate with us outside of this project, write to us. We would love to hear from you.

Follow us and stay updated about our work: