Restoring Landscapes and Improving Farmer Income, the People-Centric Way

Prarambha facilitated the workshop we detail in this article. WELL Labs has been working with this grassroots organisation for over a year to restore degraded land and improve farmer incomes and livelihoods in Raichur district.

(Scroll to the end to see more pictures of the workshop and group discussions.)

Malappa K. holds two acres of land in Mukkanal village in northern Karnataka’s Raichur district where he grows cotton during the kharif season (monsoon) and pearl millet during rabi (winter). He is worried because land degradation is causing his yields to plummet, severely affecting his income.

If he switched to a traditional intercropping approach, things might start to look up. Through intercropping, he could continue to grow cotton as the main crop during kharif, pearl millet during rabi, and – during both seasons – allocate 30 per cent of land for companion crops (mainly pulses, millets and oil seeds). Malappa could use these crops for consumption and for livestock. The surplus could be sold in the market, adding to his income.

Additionally, by transitioning from chemically-intensive methods to a low-input package of practices (such as using green manure), Malappa could reduce his expenses and, in effect, increase his net income.

And that’s not all. Enabling access to facilities like storage houses can provide farmers with the flexibility of deciding when to sell the harvested produce, rather than being forced to sell at a lower price just after harvest. Similarly, facilitating other livelihood options like livestock rearing and poultry would also increase farmer income.

This would be an initial set of farm-scale interventions. What’s key is that we start small, build trust with farmers to support them on a pathway to ecologically-sustainable and economically-viable rural futures.

An important step in this process was a workshop we held with Malappa and other farmers in March 2023. His land is part of a contiguous swathe of degraded land that WELL Labs and our grassroots partner, Prarambha, have identified as part of an ambitious project in the district of Raichur. Our goal is to restore the land to a state that yields net positive farmer incomes. We aim to do this by introducing a range of practices — from amending poor soil quality to identifying alternative sources of farmer income.

Left: Pearl millet is the major rabi crop in the village, cultivated mainly for self consumption and for livestock. Right: Saplings start to sprout three days after it was sown on degraded land treated with green leaf manure. Credit: Manjunatha G. and Syamkrishna P. Aryan.

Through months of field research and analysis, we have reached a point where we can ascertain the different options available to farmers. But this is only half the job done.

A cornerstone of our work is that projects planned for a particular landscape have to be people-centric and demand-driven for it to succeed in the long term.

This means that we actively factor in the concerns and aspirations of affected communities. This workshop was to consult with them on what we found were potential best practices and understand what they felt was realistic and keen on experimenting with.

In this blog post, we summarise some of our learnings from this novel workshop. But first, a little background on the rationale behind the work being done by the Rural Futures team at WELL Labs and the different pieces of work that preceded this workshop.

Degradation of agricultural land is widespread

Around 30% (97.85 million hectares, which is around 242 million acres) of India’s total geographical area is degraded. This presents a critical socio-environmental challenge for the country. Of this, nearly 37 million hectares (~ 91 million acres) is rainfed agricultural land, of which around 80% is owned by small and marginal farmers.

Read Op-ed in IDR | Climate mitigation: Can carbon credits ensure farmers don’t pay the price?

The causes of degradation are numerous, including chemical-intensive monoculture practices, improper land management, and soil erosion. As a result, farmers in these areas struggle with maintaining sustainable agricultural production. This has led to falling farmer incomes, forcing many farming households to migrate to cities in search of work.

Restoration of degraded agricultural land will be sustainable only if it is accompanied by measures to prevent further degradation. This requires incentivising farmers to adopt sustainable agricultural practices. To scale up these transitions, it is crucial to ensure that sustainable agriculture practices are economically viable for smallholder farmers and positively impact ecological parameters such as soil health, groundwater tables, and biodiversity. This could be achieved by supplementing agricultural revenues with value addition of farm produce and income diversification activities.

Farmers’ intervention options and aspirations are often limited by their current resources, constraints and knowledge, making it critical to provide a bouquet of intervention options that are best suited to their needs.

Yields are reducing, expenses are increasing and the net income is on the decline

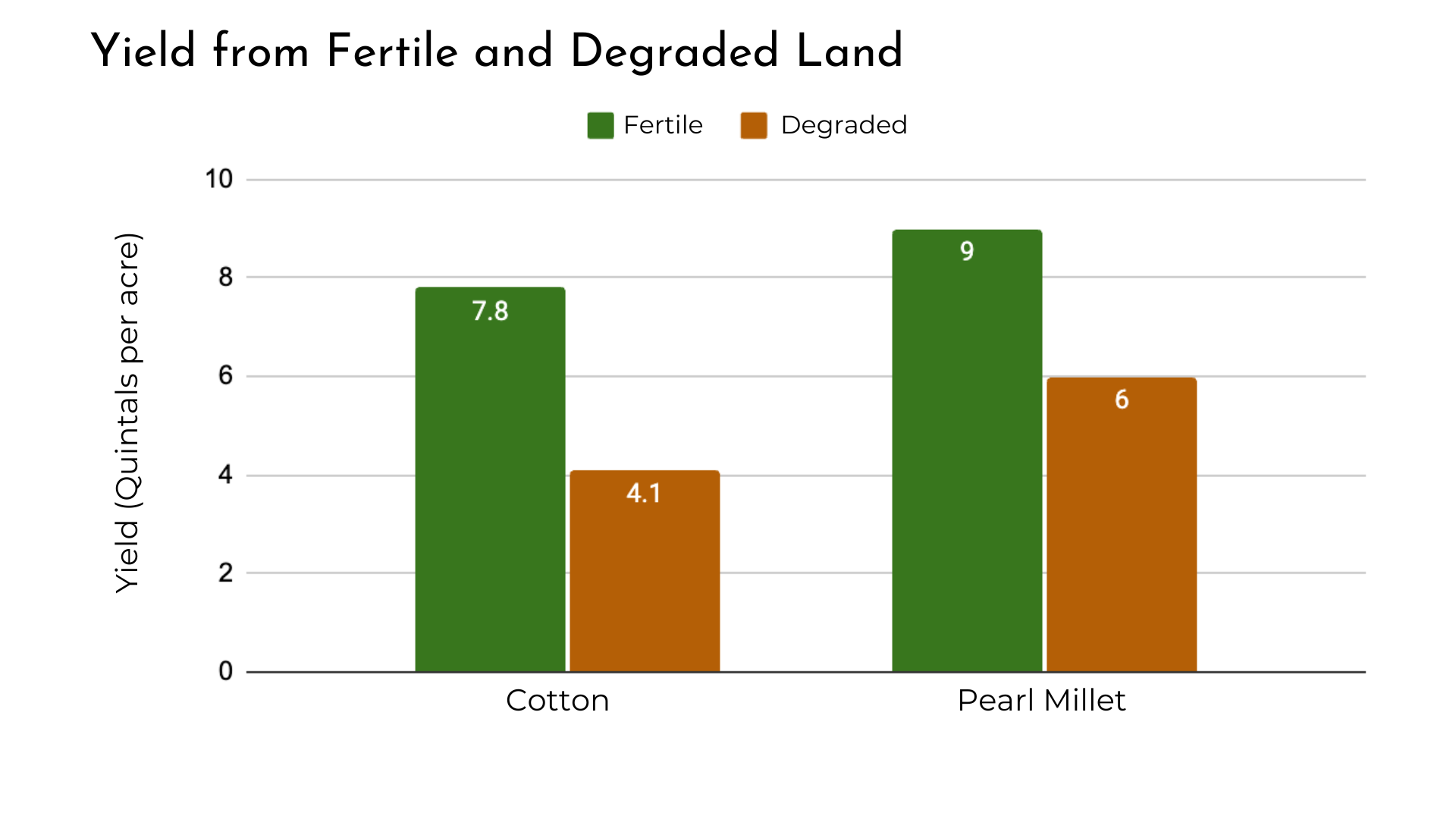

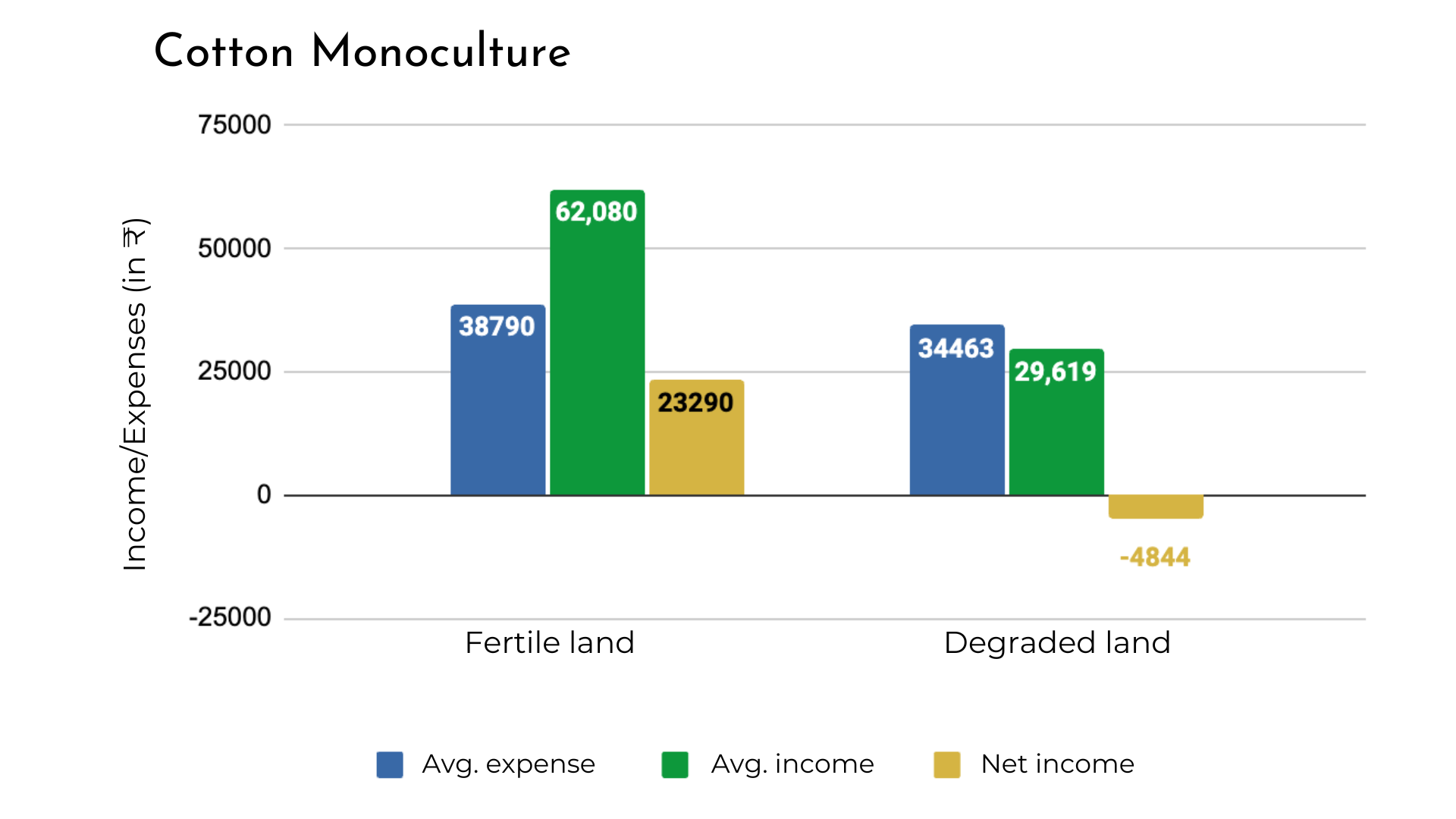

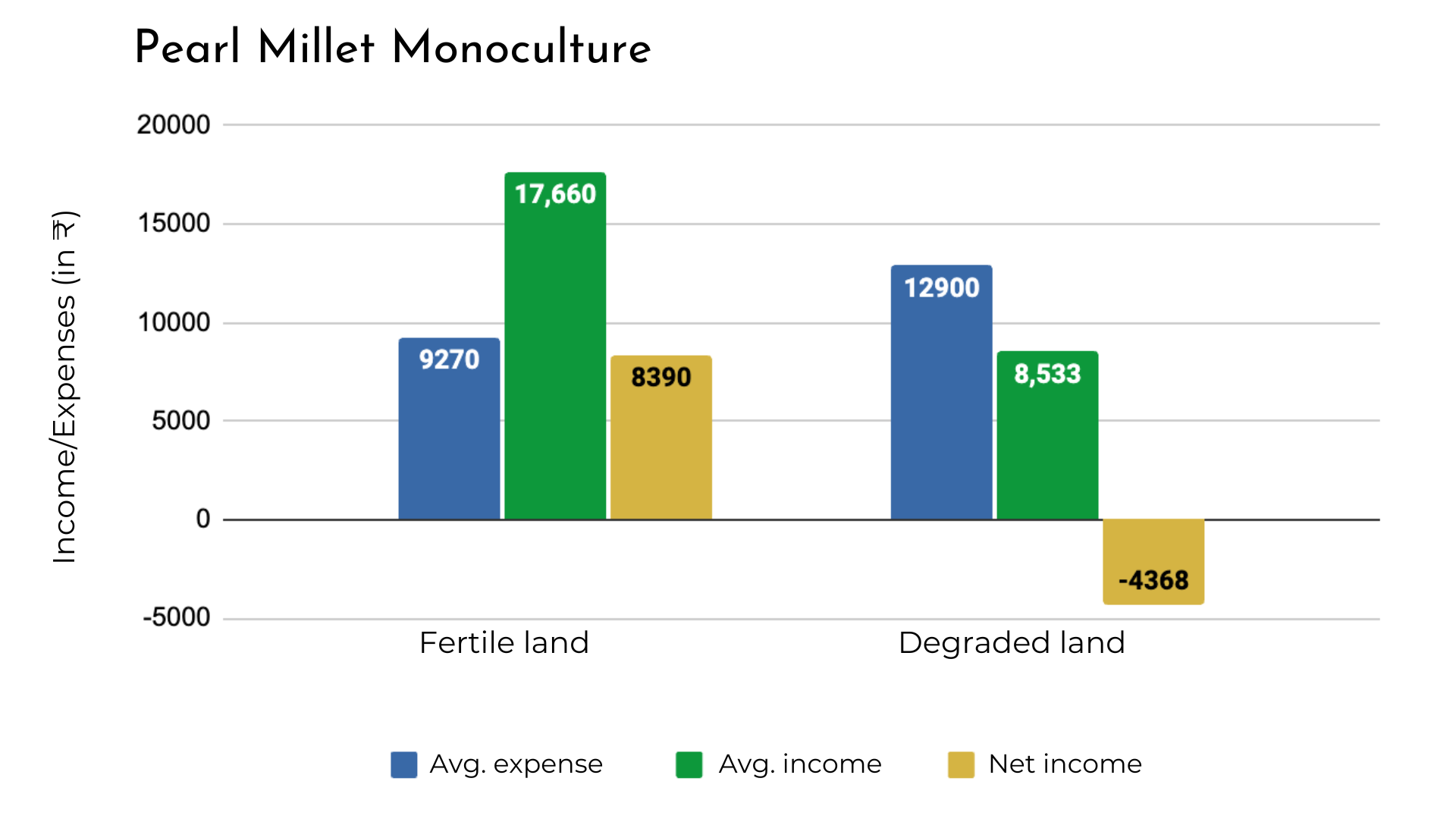

Most of the farmers in Mukkanal village, who attended this workshop, have a patch of comparatively fertile land in other parts of the village, which they survive on. A comparison of per acre incomes and expenditure from both patches of land (degraded and fertile) shows the impact of land degradation on farmer incomes.

These graphs show the difference in net income between fertile and degraded land used to cultivate monocultures of cotton and pearl millet.

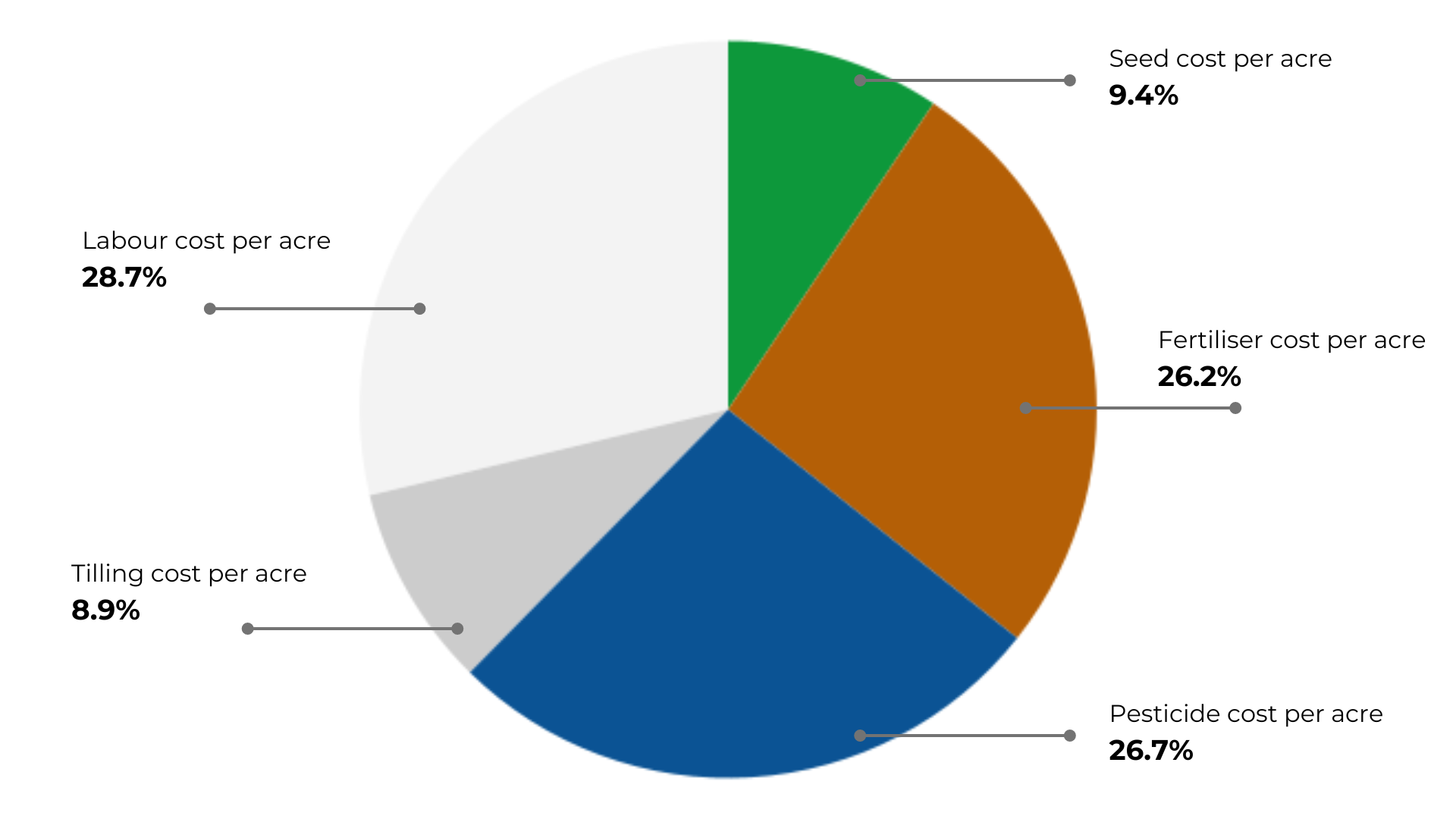

A major reason why expenses continue to rise is the costs for inputs; it is estimated that Rs. 53 out of every 100 spent on agriculture is towards fertilisers and pesticides.

Break-up of agricultural expenses (based on findings from the journey mapping exercise we conducted in Mukkanal village, Raichur)

We conducted journey mapping and aspirational studies to assess best possible options.

It is against this context that we conducted two studies to assess the baseline of different conditions here and also to qualitatively capture what farming households said they need and aspire for. Key learnings include:

- Land degradation is a significant risk that has led to decreased productivity and reduced farmer income. Farmers depend on monocultures and face rising input costs and extreme weather. They spend most on fertilisers, pesticides and labour.

- Cotton is the most popular crop choice, as it grows well even on degraded land. Pearl millet is also commonly grown due to its low input costs and is consumed by both people and livestock. However, the popularity of pigeon pea is declining due to low yield and crop loss lowering farmer incomes.

- Many of them faced negative migration experiences, which highlights the need to improve the sector’s overall profitability and thus rein in distress-driven migration.

- Farmer mainly require irrigation sources and options to diversity their livelihood. Many farmers also expressed the desire to increase the number of livestock, mainly sheep, and put up infrastructure to support them.

A range of restoration or pre-sowing activities needs to be part of the intervention design.

Since land degradation is a critical bottleneck to address, such activities are already underway in the village with the support of Prarambha. When we visited in March, farmers were preparing the land for the next agricultural season with green leaves manure (to restore soil quality) and trench cum bunds (to manage water better).

Similarly, to prevent further degradation, it doesn’t make sense to follow the same chemical-intensive monoculture approach even after restoration — it is important to consider an alternative package of practices:

Crop diversification is important to avoid unexpected risks due to climate or market variations and stagger farmer income through the year.

Income diversification options (like livestock rearing) need to be considered as a component in the intervention design. This would help farmers manage potential risks associated with cultivation in the context of climate and market vulnerabilities, thus making farmer incomes a little more stable.

Value addition of agricultural produce should also be explored as a component in the intervention design for better revenue realisation for the farmer and to address the problem of market access.

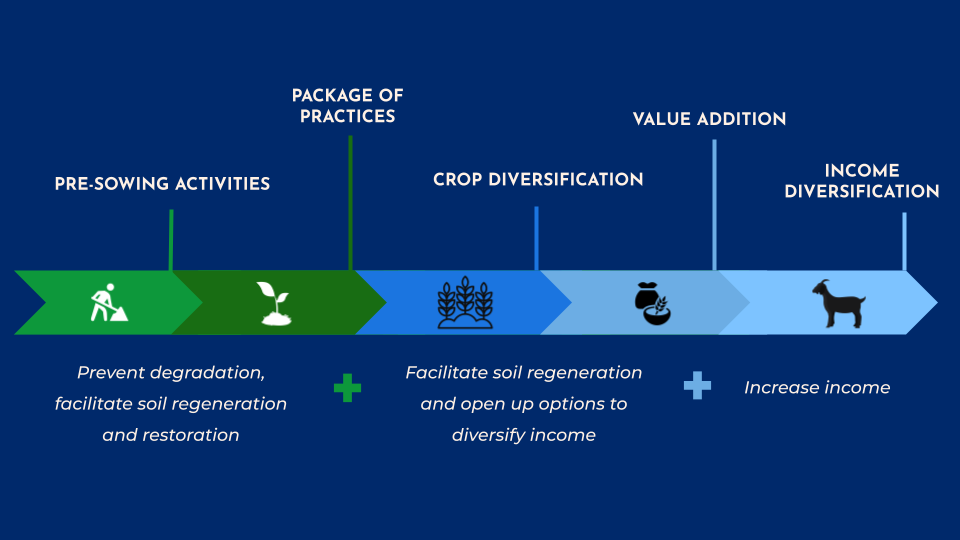

These were the three components that we focused on during the workshop (on the right in the image below in shades of blue).

Different intervention options mapped across the farming cycle. The farmer workshop focused on the three components on the right (in shades of blue) — crop diversification, value addition and income diversification.

Unique farmer consultation workshop for farmers to make informed choices

The objective of the workshop was to provide farmers with a range of intervention options derived from the aspiration study and journey mapping exercise. We believe this could help them make informed choices on how to restore degraded agricultural land, prevent further degradation, and improver farmer incomes in a sustainable and scalable manner.

WELL Labs, in partnership with Prarambha and the local farming community in Mukkanal, organised the workshop. We aimed to increase awareness among farmers, understand specific interests ahead of the next agricultural season, and document concerns and suggestions regarding these interventions and how to prioritises.

Read | Soil Workshop in Raichur: Farmers Keen to Try New Methods to Rebuild Soils

The farmer workshop had more than 30 active participants including women and youth, representing the degraded agricultural lands in Mukkanal we identified for restoration. They were divided into three different smaller groups to discuss intervention options and individual or collective interests. One coordinator in each group asked four different questions each with a set of options. They also explained each option for farmers to make an informed decision.

As mentioned above, for this workshop, we focused on only three aspects of the intervention design — crop diversification, value addition and income diversification. The restoration component is already started in the pilot lands based on the site specific assessment performed by Prarambha. The package of practices needs to be discussed and decided by the farmers collectively later after they decide on other aspects.

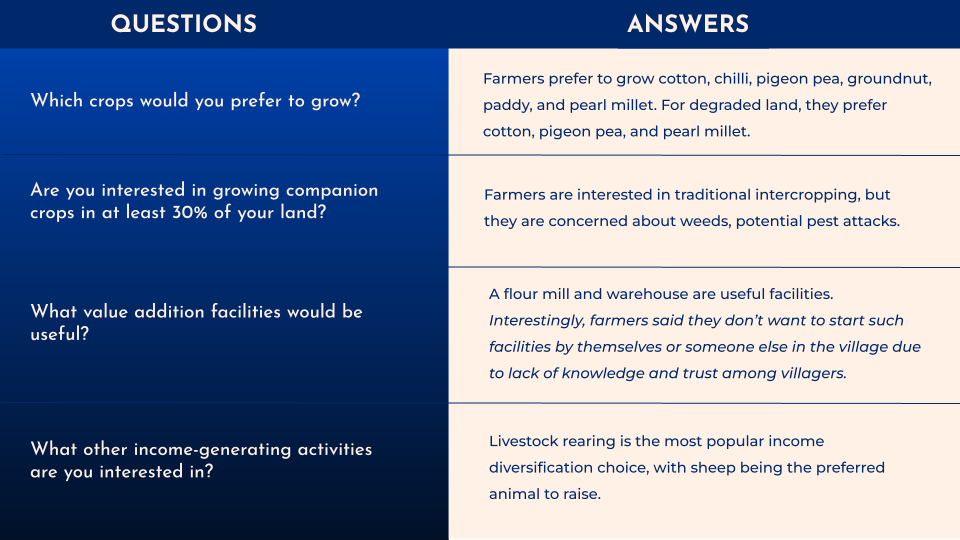

Some of the key questions we raised during the workshop alongside a summary of responses.

Interestingly, the farmers’ responses were not influenced much by the set of options provided. They didn’t go beyond their previously known options while choosing the interventions. This is because farmers were generally risk averse in their responses. Nobody was individually volunteering for any of the new intervention options; but was ready to try if others also join.

Farmers expressed interested in a few shifts from their existing practices:

Intercropping

After 2-3 workshops about Akkadi Saalu, a traditional intercropping method, most farmers were interested in allowing companion crops in 30% of their degraded lands.

Indigenous varieties

Provided there is a buyback guarantee and better return compared to Bt cotton, farmers said they would consider switching to indigenous varieties of cotton.

Warehouses and livestock

There was interest in accessing a warehouse from a producer point of view and in a flour mill from a consumer point of view. Farmers were also keen on livestock rearing.

Newer interventions

There was also a general interest to know more about the intervention options like agro voltaics, agroforestry etc.

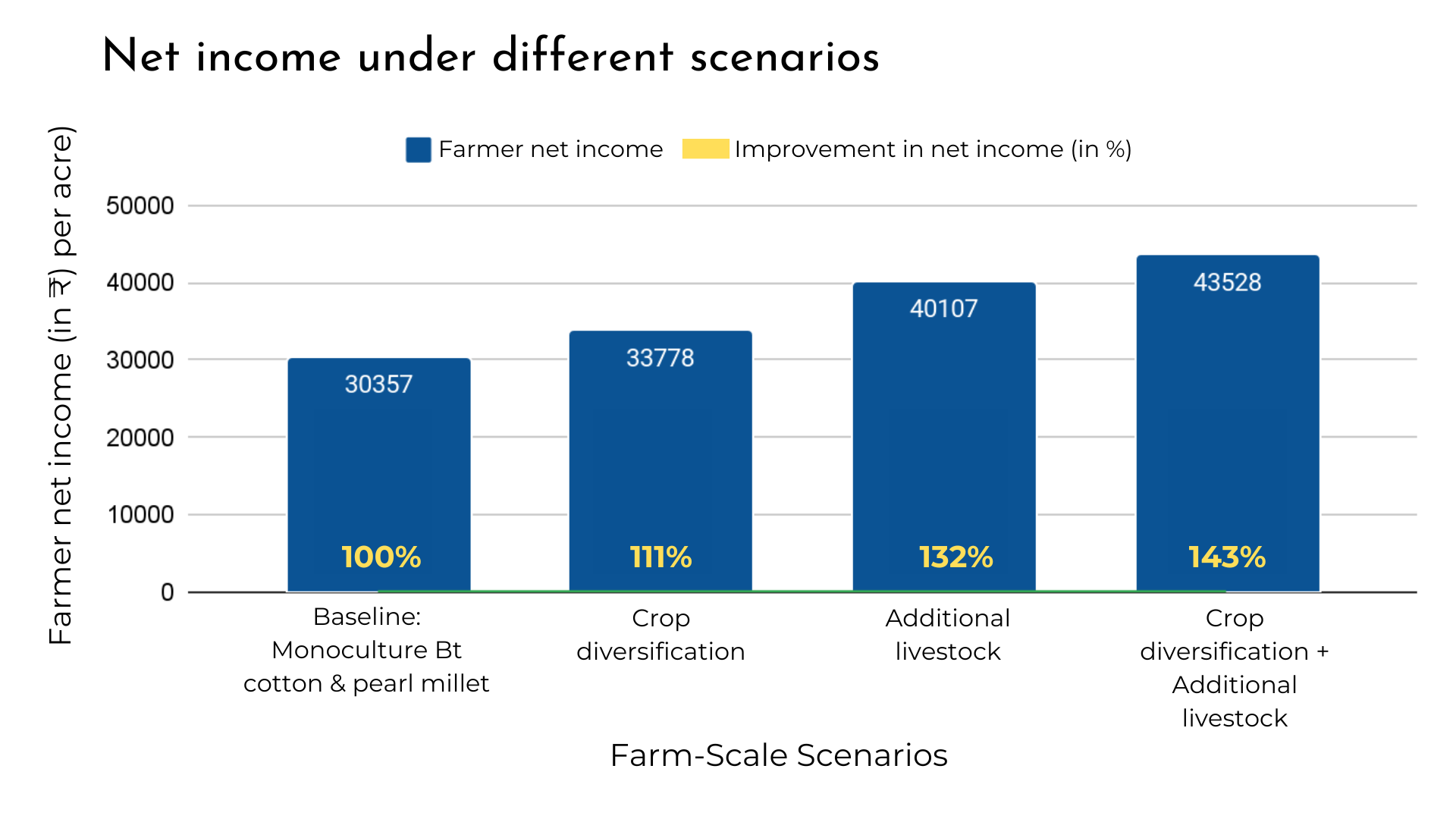

Let’s look at Malappa’s story again. The chart below shows around 43% potential improvement in net farmer income with a handful of initial interventions alone including switching to traditional intercropping and additional livestock.

This graph shows by how much farmers’ net income could potentially improve. Source: Farm-scale modelling the author carried out based on secondary data. We will detail this modelling exercise in a separate blog post.

There is potential for Malappa to see considerable impact on his expenses and income, while restoring the landscape. It is a huge first step given that there are complex processes and multiple stakeholders involved. Moving the needle is slow and iterative.

We continue to work with these farmers and we’ll document each stage of the restoration project. We will also detail the modelling exercise we conducted that helped us arrive at the estimated increase in farmer income as a result of these interventions.

Top left: The workshop started with the screening of a documentary film on Mukkanal village directed by Sushma Veerappa, trustee of Udaanta — a trust working to promote indigenous cotton seeds — who also participated in the workshop. Top right: Representatives from Prarambha, WELL Labs, SOIL Trust, Udaanta and SayTrees brainstorming on the workshop structure and how each organisation could contribute in the long term. Bottom row: Two groups of farmers discuss their plans for the next agricultural season. Credit: Manjunatha G. and Syamkrishna P. Aryan.

The author acknowledges inputs from WELL Labs researchers Sandeep Hanchanale, Ananya Rao and Manjunatha G, and our grassroots partner, Prarambha.

Edited by Kaavya Kumar

If you would like to collaborate, write to us. We would love to hear from you.

Follow us and stay updated about our work: