Explainer: How Green Manure Can Help Degraded Farmlands Sustain Themselves

A rotavator crushes a row of plants to create manure. Photo by Revanna Siddappa, Prarambha

Plants grown for green leaves manure being observed in Malakasamudra village. Photo by Vishwanath Koppal

Understanding the recipe

Green manure is essentially the organic matter obtained from green leaves, stems, and roots of plants. It can be created within 45 days – making it feasible even for farms with shorter cropping cycles – and from natural materials at low cost. Karnataka has one of the highest chemical fertiliser consumption rates in the country, at around 71 kgs per hectare in recent years – depending only on these fertilisers can be expensive for a farmer, so green leaves manure makes a cost-effective partial add-on, not a complete substitute. Here, we look into two cases of farmers who have practised this technique for years, making green manure from scratch on the very land it is meant to sustain – one in Karnataka and the other in Telangana.Measurements are key for good manure

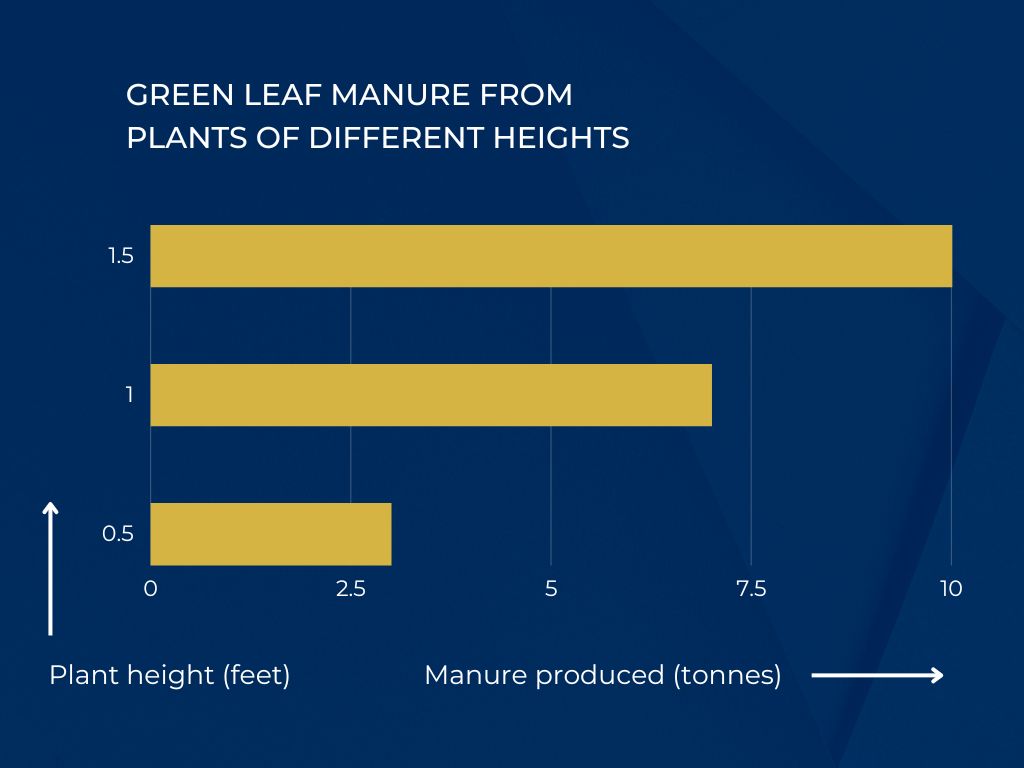

For Prabhakar, who sows 30 kgs of seeds, the amount of manure yielded depends on which seeds he sowed and how tall the plants could grow in 45 days. If the plants grow half a foot, they amount to three tonnes; at one foot, the yield is seven tonnes; and if their growth is 1.5 feet before crushing, he gets 10 tonnes of green manure to give back to his soil. The seeds he sows for this are usually three kinds of monocots (like pearl millets, sorghum and maize), three kinds of dicots (like cowpeas, chickpeas and green gram) and three kinds of oilseeds. On the other hand, Anumula Ramreddy explains on his YouTube channel how his green manure is made from different proportions of dhaincha seed, sunn hemp seeds (janumu vithanalu), cow pea (bobbarlu), horse gram (ulavalu), pearl millet (sajjalu), broad beans (anumulu), hyacinth beans, coriander seeds (dhaniyalu), sesame seeds (nuvvulu), and fenugreek seeds (menthulu).

Amount of green leaf manure Prabhakar can make when his plants reach heights of 0.5 feet, 1 foot and 1.5 feet

Along similar lines at our site in Raichur, we sowed 30 kgs of seeds. We had decided on a combination of four types: three monocots, three dicots, three oil seeds and a mix of dill seeds including coriander and fenugreek.

After 45 days of growing, then harvesting and crushing, these seeds yielded a total of four to five tonnes of green leaves manure per acre, distributed across lands of varying degradation levels. In Koppal, we managed to create five tonnes of manure for the same input.

Weighing the pros and cons

For Prabhakar and Anumula, the total green manuring cost is less than ₹5,000 per acre, while depending entirely on chemical fertilisers would have cost anywhere between ₹10,000 and ₹15,000 per acre. This difference in cost not only breaks a vicious cycle of expenses, but also promotes self-sufficiency with farmers making green manure in their own time, as per their needs and schedules, instead of having to wait for affordable fertilisers in the market.

It also puts a stopper on another domino effect that is caused by chemical inputs like urea, whose need for dilution through irrigation often surpasses the moisture needs of the actual crop. Crops need adequate but not too much irrigation – they need moisture and organic matter that can hold moisture. On the other hand, it is chemical fertilisers that need irrigation to dilute their effects. Over-irrigation can pull salty content from the ground to the surface; canal irrigation can sometimes lead to high salinity for this reason. This might worsen the fertility of the land. Green manure can bypass this phenomenon entirely. The manure also stays longer in the soil, yielding benefits throughout the year, as compared to market fertilisers whose benefits are absorbed within the first few days.

Farmers uproot plants to be crushed for manure in Raichur. Photo by Revanna Siddappa.

Access to seeds for manure is an issue

Appealing as these benefits are, not all farmers have the means to make their own green leaves manure. Access to seeds is an issue – not all farms yield crops that are rich in seed, so they often have to be bought at market cost. In the pilot sites, WELL Labs had to procure most of the seeds from private sellers and shops, including some from neighbouring districts. Government agencies dedicated to providing support to farmers, often do not have all seeds types needed for GLM, since they serve a different purpose – their stocks of specific seeds are meant to aid harvest and income-generating yields.