Part 1: Journey Mapping to Plan the Future of Mukkanal’s Farmers

Pesticides being sprayed on paddy fields in Raichur, Karnataka. Photo by Manjunatha G.

“Thirty years ago, my grandfather used to cultivate redgram, greengram, sesame, and various millets on this land. Now, the land cannot support any of these crops anymore. In fact, it can’t support any crops at all — it has been lying fallow for two decades.”

Devappa (name changed) tells us that he has only heard stories of how productive his family’s land used to be. He is a forty-year-old farmer who tills the land in Mukkanal village in Karnataka’s Raichur district. This region, in the north-eastern corner of the state, is drought-prone and fares poorly in terms of human development and agricultural productivity.

Devappa is one among 17 farmers whose degraded farmland is part of a land restoration pilot we are carrying out. The pilot aims to restore 27 hectares (about 67 acres) of agricultural land and 97 hectares (about 240 acres) of common land located in Devadurga taluk of Raichur district.

We began the pilot with a baseline socio-economic assessment of the pilot area in September last year — an account of those early stages can be found here. A critical next step is a journey mapping exercise that would give us a much deeper understanding of livelihood patterns, how people make decisions and what challenges they face. These insights will inform the restoration steps for this region.

We carried out a journey mapping study with the 17 households that fall within our pilot site of 27 hectares of agricultural land. In this two part blog series, we detail how we went about this exercise and key findings so far.

Farmers engaged in a discussion in Mukkanal. Photo by Manjunatha G

Journey mapping traces how an actor is affected by a process

It is a methodology that has grown popular across sectors because it helps visualise the steps that an actor takes to reach a goal. Under journey mapping, each task or activity is placed on a timeline, different stakeholders are mapped out, outputs are listed and – most importantly – ‘pain points’ or challenges are identified.

We had previously used this method in 2021 to gather data on how civil society organisations plan and implement different solutions (such as watershed management or agroforestry) and the roadblocks they face.

In the context of land restoration, our aim was to use the insights from journey mapping to design interventions that are actually useful to the local community, and cater to the specific needs, challenges and preferences of each household.

Since agricultural challenges are multi-faceted and complex, we decided to focus on one aspect – livelihoods. Our interview questions were geared towards clarifying current livelihood patterns of these 17 households, challenges and main requirements in augmenting farm and non-farm livelihoods, and how these households make decisions.

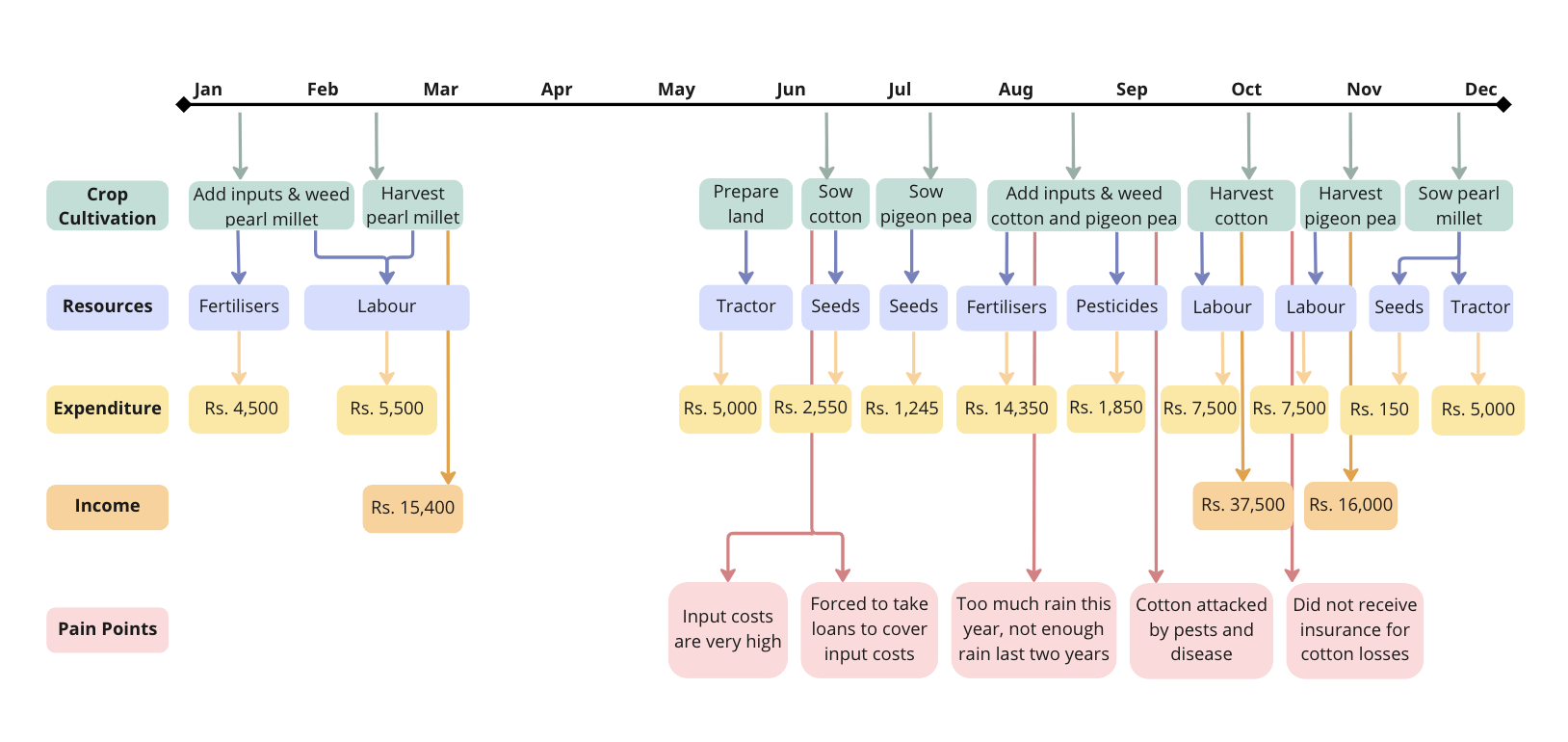

A sample of a journey map illustrating a single farmer’s crop calendar (based on insights from one of the 17 farmers we interviewed) The diagram captures key activities, resources required, expenditure, income as well the challenges or ‘pain points’ they face.

We began the journey mapping with focus group discussions

The focus group comprised representatives from all 17 families whose land is part of the restoration pilot. It was conducted by representatives from ATREE and Prarambha, an NGO based in northern Karnataka we partnered with to implement restoration work. The primary agenda of this discussion was to share results from the four baseline assessments, on soil characteristics, hydrology, biodiversity and socio-economic conditions, we conducted at the pilot site in September 2022.

We then proposed to the farmers a possible set of interventions that could be carried out in the region based on the findings from the baseline assessments. These interventions included practices such as layered agroforestry and mixed cropping, among others. Given that our restoration work hinges on the needs and aspirations of affected communities, it was important for us to record their responses to these potential interventions. This feedback will be incorporated to ensure that potential solutions actually address the problems faced by the people it is meant for.

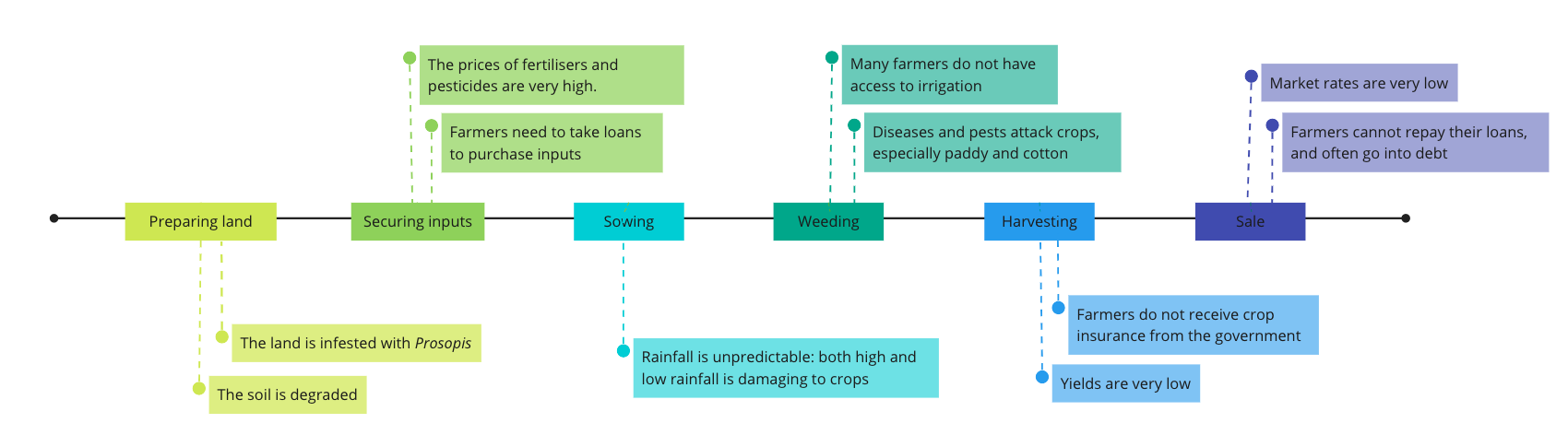

This journey map details pain points associated with each stage of agricultural production, for the group as a whole.

Our journey mapping interview questions ranged from the specific to the open-ended

This focus group discussion was followed by individual journey mapping exercises with one representative from each of the 17 families. These were semi-structured interviews of 40 to 50 minutes each, held in people’s homes or on their farms, where they felt more comfortable.

Some of the questions we asked were straightforward, such as how much they spend or earn, which respondents found easier to answer. Most struggled to estimate annual finances, but easily gave exact figures for weekly finances as well as amounts involved in specific inputs for each activity.

Conversations around broader challenges were trickier and we had to ask a series of follow-up questions to glean a clear picture from the respondents.

At the end of the journey mapping process, we collected two kinds of data:

Firstly: quantitative data on annual income and expenditure for each household. This covered expenditure on agriculture, animal husbandry and household expenses (on groceries and school supplies). It also covered income from agriculture, animal husbandry, migration, wages through the National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (NREGA), agricultural labour and other sources, if any.

Secondly: qualitative data on the challenges each household faces. This includes challenges in livelihood practices (primarily agriculture) over the past two decades. It also includes the drivers behind their important livelihood-related decisions

Though our sample size was small, these journey mapping interviews threw up some important insights on how farmers like Devappa, who live in this part of semi-arid India, grapple with the impacts of land degradation and outline possible ways forward.

In the next part of this blog series, we will delve into some preliminary findings from this journey mapping exercise.

Credits

The author conducted this work when she was with the Centre for Social and Environmental Innovation at the Ashoka Trust for Research in Ecology and the Environment (CSEI-ATREE). WELL Labs is now taking it forward in collaboration with ATREE.

Edited by Meghna Majumdar and Kaavya Kumar

If you would like to collaborate with us outside of this project or position, write to us. We would love to hear from you.

Follow us and stay updated about our work: