Lake Rejuvenation Can Resolve Urban Water Issues, But Only if Done Scientifically

With climate change, many regions are experiencing extreme variability in rainfall. In 2023, Karnataka faced a drought regarded as the worst in 123 years. The year before, however, the state saw rainfall exceeding its annual average by almost a third! While the state experienced drought in 16 of the past 23 years, it also witnessed recurrent floods. Indian cities, with their burgeoning population and haphazard development, are especially vulnerable to water shortages and deluges.

To mitigate these problems, both residents and government officials have rallied to rejuvenate polluted, encroached lakes.

Water bodies can be a source of drinking water, help with groundwater recharge and build resilience against floods, apart from a host of other benefits. However, many lake rejuvenation projects focus on surface-level beautification, such as walkways and concretisation. At times, planners treat restoration as merely an engineering project, which ignores its ecology and communities’ needs. They do not follow comprehensive approaches to lake rejuvenation, goal-setting, monitoring and evaluation.

So, how can we go about restoring lakes to not only build water security and resilience but also cater to communities’ aspirations and complex ecological systems?

Let’s take the case of Chintamani, a small town located 75 km northeast of Bengaluru in the state of Karnataka. The town has limited water resources — characteristic of the Deccan Plateau’s semi-arid regions. Most residents of Chintamani receive water once a week despite the municipality pumping borewells 24/7.

There are no major rivers nearby and the town is overwhelmingly dependent on groundwater. But in the absence of sufficient rainfall, many of Chintamani’s borewells fail. In 2018, it received only about half of its average annual rainfall. Most borewells dried up in 2018–19 and residents depended entirely on tankers that brought water from afar. It was reported that the municipality used to hire 300-400 tankers to meet water requirements.

Chintamani, a small town located 75 km northeast of Bengaluru in the state of Karnataka, has limited water resources. Photo by TIDE & BORDA.

Chintamani’s water situation might seem dire, but there is a solution within: its lakes.

Water bodies such as Nekkundi, Kannampalli, Mallapalli and Gopasandra constitute 4% of the town’s area. However, the municipality draws water only from the 11-acre Kannampalli lake. It accounts for a fifth of the municipal supply, with the remainder coming from groundwater. The rest of the lakes are polluted due to the inflow of sewage as the town treats only about a third of the wastewater it generates. If these lakes were cleaned, Chintamani could potentially meet up to 50% of its drinking water needs through them.

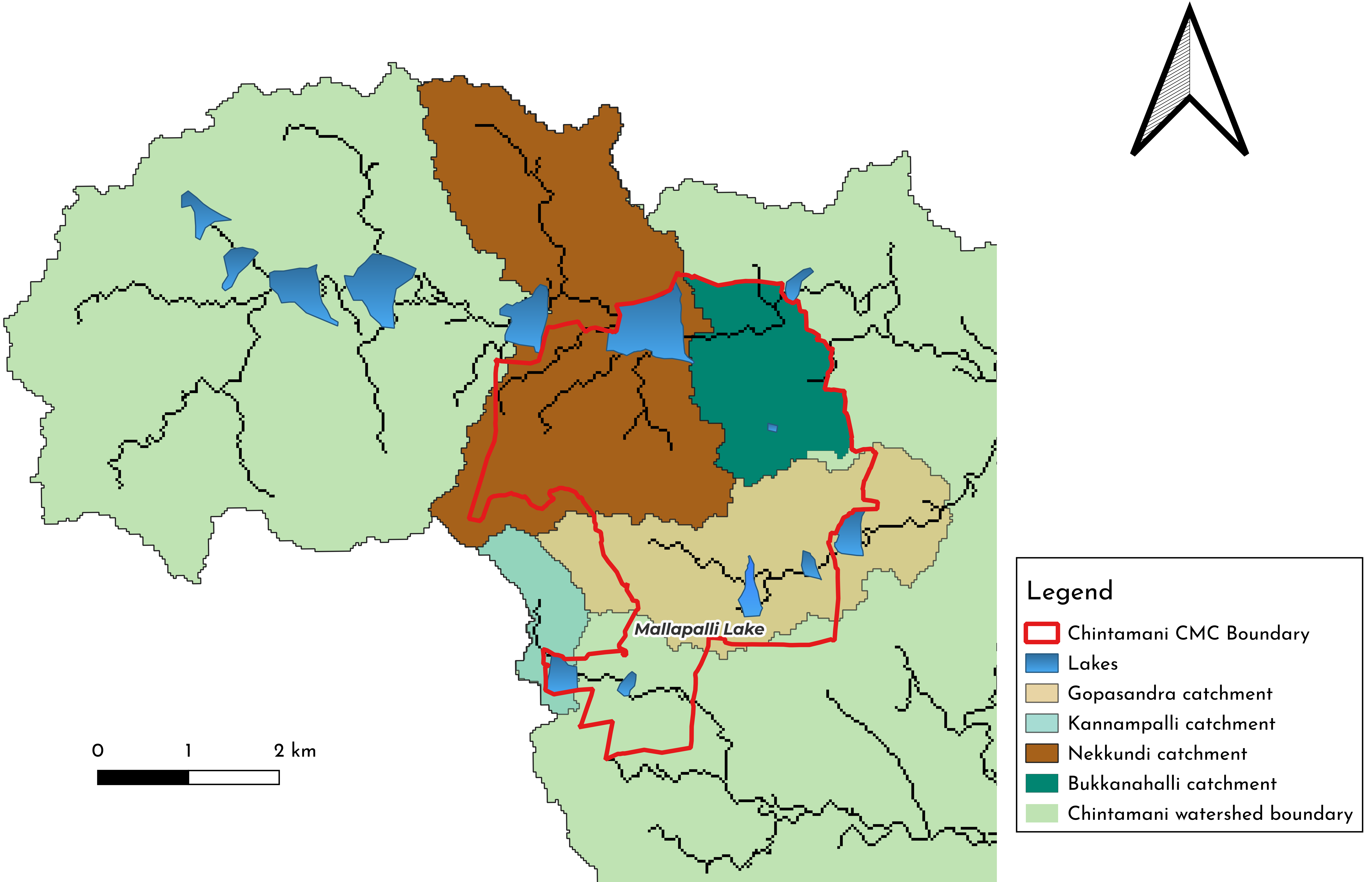

A map depicting the catchments of Chintamani’s lakes. The red line delineates the Chintamani Municipal Corporation’s boundary.

Map by Shashank Palur.

To demonstrate a scientific approach to lake rejuvenation in Chintamani, WELL Labs has partnered with DCB Bank and Friends of Lakes.

We selected Mallapalli Lake as the intervention site since the availability of drinking water is a priority for the town and resistivity surveys indicate that the lake’s bedrock is low, due to which it has a significant water-holding capacity.

DCB Bank’s CSR arm, which focuses on water conservation, waste management, and renewable energy, among other domains, is funding the initiative. Friends of Lakes, a group that conserves lakes, is restoring the Mallapalli Lake and conducting baseline studies and stakeholder consultations.

Through this project, WELL Labs will take forward its earlier initiative of assessing the town’s water and wastewater management scenario through household surveys, resistivity surveys and interviews with municipal officials. We shall present these insights in a water balance assessment report for Chintamani in collaboration with TIDE and BORDA.

Kanampalli Lake accounts for a fifth of Chintamani’s municipal water supply. Photo by TIDE and BORDA.

For successful restoration, it is crucial to identify the desired purpose of a lake. The water quality parameters, lake design, etc. would vary as per this purpose. A lake intended for fisheries, for example, would be different from one meant to provide drinking water or recreation activities.

To ensure that communities’ aspirations drive lake restoration and there is consensus on the vision and goals, we are conducting participatory lake visioning exercises with residents, municipal officials and other stakeholders. We are documenting this process as a guiding resource for rejuvenation efforts. In addition, we are mapping residents’ vulnerabilities with respect to water and sanitation.

We are also holding consultations with experts across the globe to determine the ‘state of the science’ on the desired end state for different kinds of lakes with varying purposes. We shall use these insights and build upon existing frameworks for the monitoring and evaluation of lake rejuvenation. This will comprise comprehensive quantitative and qualitative parameters that accurately represent lake health.

Our immediate goal is to increase water availability in Chintamani through the restoration of Mallapalli Lake and simultaneously demonstrate successful participatory lake visioning, monitoring and evaluation.

We hope this will act as a catalyst for our medium-term goal: to make Chintamani more water secure through the rejuvenation of other key lakes. Eventually, we seek to integrate our findings with existing frameworks for lake rejuvenation so that better planning, implementation, monitoring and evaluation of such projects can contribute to water security and resilience in urban settlements.

With inputs from Shreya Nath

Banner photo by TIDE & BORDA

Edited by Kaavya Kumar

If you would like to collaborate, write to us. We would love to hear from you.

Follow us to stay updated about our work.