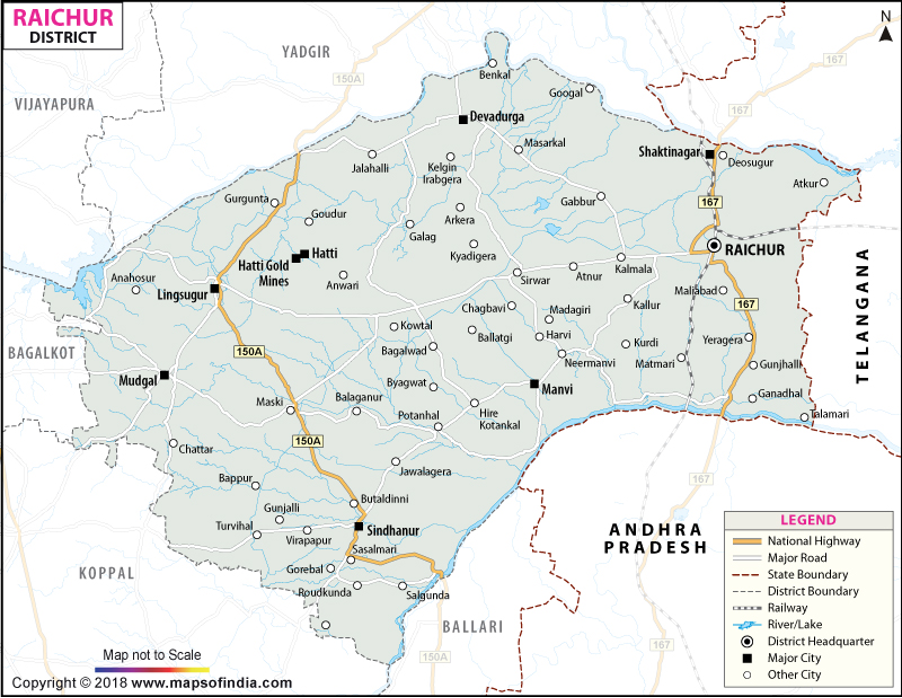

Land degradation, or a deterioration in land quality caused by human-induced processes, is a massive challenge for India today. Approximately 53 million hectares (MHa) of land in the country is already degraded. This implies a massive reduction in biological and economic productivity. To address the issue of degraded lands at scale, we initiated a pilot in the Raichur district of Karnataka. We based it on the AREST approach of adopting a people-centric, demand-based assessment for restoration. AREST is the Alliance for Reversing Ecosystem Service Threats.

This pilot began with baseline assessments that put together a comprehensive picture of the current state of soil conditions, water quality, and socio-economic indices in the regions where we have initiated restoration activities.

Read | AREST’s Seven-Step Plan to Restore Degraded Land in Peninsular India

In this blog post, we describe our research and decision-making processes in the early stages of the Raichur land restoration pilot project. We explain why we chose this location, what questions we asked, and what our broad learnings have been so far, even as the full body of data collected by us is currently being studied and reviewed. The said data will form the foundation of our baseline socio-economic assessment of Raichur, which will influence and direct the restoration steps we take for this project.

Raichur is a climate-vulnerable district with poor socio-economic development indicators.

Enlisted as an aspirational district by the Government of India, Raichur falls in the semi-arid agro-ecological zone of the Deccan Plateau. It is highly drought-prone and fares poorly on the human development index. A high proportion of women and children below the age of five are anaemic in the district.

It also fares poorly on several agro-biodiversity indicators, due to monoculture agricultural practices and excessive and ad-hoc use of fertilisers and pesticides. This emerged from the intensification of rice, cotton and chilli cultivation in the district in the past two decades, owing to irrigation projects of Tungabhadra and Krishna rivers bordering the district.

In the rainfed areas of the district, anecdotal evidence indicates deteriorating soil quality and lowered agricultural productivity, rendering agriculture a marginal income source, and instigating high levels of distress migration. In the irrigated parts of the district, chemical degradation of soils was also evident.

The total irrigated area in the district makes up 19.6% of the total geographical area and 26.2% of the cultivable land.

In Raichur, we selected three villages as pilot sites for intervention.

We identified 100 hectares of rainfed commons and agricultural land in the western part of the district, in Amarapura Gram Panchayat of Devadurga Taluk, as pilot sites, after local interactions and with Prarambha, our grassroot partners for implementation of restoration solutions.

Here, in consultation with the local communities, we selected three villages as sites for intervention: Mukkanal, Parapur, and Gajaldinne. There are two types of degraded landscapes being restored under this pilot. The first is 27 hectares of agricultural land located entirely in Mukkanal and belonging to 20 farmers. The second is 97 hectares of commons land that is used jointly by all three villages.

We kick-started the pilot with four baseline assessments; soil, water, biodiversity, and socio-economic indicators, followed by an aspirations study with our partners, Sarvodaya. The socio-economic baseline, assessing current land-use and livelihoods, was conducted at the village-level, and formed the context for the aspirational study, which was conducted at the individual-level and unpacked people’s future goals.

These five studies dovetail to create a comprehensive picture.

They show us the drivers of land degradation, how it is affecting people, their aspirations, current and future land-use demand and what potential interventions can reverse the damage.

In the rainfed areas of the district, anecdotal evidence indicates deteriorating soil quality and lowered agricultural productivity, rendering agriculture a marginal income source, and instigating high levels of distress migration. In the irrigated parts of the district, chemical degradation of soils was also evident.

The total irrigated area in the district makes up 19.6% of the total geographical area and 26.2% of the cultivable land.

We used a combination of methods.

The socio-economic baseline assessment was conducted through a combination of focus group discussions, individual interviews, and secondary data collection (consisting of village and district level government data and reports). In each of the three villages, two focus group discussions were conducted, one with men and another with women, to ensure the data is gender disaggregated. From past studies, we know that land degradation challenges and end-user demand from a restored landscape are gendered.

Additionally, in Mukkanal village, we spoke with at least seven of the 20 farmers whose land we are working with, to specifically understand their agricultural productivity. Secondary data was collected from the gram panchayat and the primary schools, anganwadis and ASHA workers in each of the three villages.

Five sets of indices were covered in the socio-economic baseline data collection:

Demographics include parameters such as population, caste, and access to infrastructure and public services.

The main purpose of including these parameters is to understand the social profile of the three villages and assess the existing standards of living.

Land use provides information on the geographic profile of the three villages.

It also includes details regarding irrigation and fallowness in agricultural land. This is important to understand the broader geographical profile of the landscape.

Livelihood covers details about five potential sources of income: agriculture, animal husbandry, agricultural labour or other informal labour, migrant remittances, and MGNREGA.

It also looks at access to government schemes that can augment livelihoods, such as the Public Distribution System (PDS) and Pradhan Mantri Fasal Bima Yojana (PMFBY). The aim of assessing these parameters is to understand the importance of agriculture as a source of livelihood, particularly in reference to other sources of income.

Commons assess the degree of dependence on common land.

This parameter also delved into the current status and health of the commons, past or current efforts at restoring or conserving the commons.

Agriculture assesses costs of inputs, costs of labour, and the profits earned from the yield.

This helps ascertain the productivity of the farmland, the quantum of profit or loss that farmers are facing, and consequently, what interventions are needed in which areas.

In each of the three villages, two focus group discussions were conducted, one with men and another with women, to ensure the data is gender disaggregated. Credit: Muddurangappa Nayaka from the Prarambha team.

The socio-economic survey revealed a few key insights.

1. Agriculture and livestock rearing are supplementary to each other

Demographic and land use data from the three villages demonstrate the importance of agriculture to the economy, as majority of the land (72.7%) is under cultivation. For many farmers in the village, however, including the 20 farmers whose land is part of the restoration pilot, agriculture is leading to losses. They are unable to cultivate crops twice a year and only cultivate three to four crops every year. In comparison, farmers who own fertile land in Mukkanal are able to cultivate seven to eight crops each year.

They are also facing losses in all the crops they are cultivating, except for cotton.

As agriculture is unanimously the most important source of livelihood for majority of the population, degraded land poses a dire threat to people’s subsistence. The livelihood profiles also show that animal husbandry is an important supplemental source of income for many. This indicates that the commons too are an important resource to conserve, given that they provide grazing area for livestock.

Read | The Uncommon Commons: Restoring Raichur’s Degraded Land

2. Access to public services is limited

The data also reveals that the residents of the villages do not receive adequate access to or support from public services and infrastructure. There is no adequate healthcare, no drainage and sanitation facilities, and no public transportation. There are also problems with availability and quality of drinking water, and the nearest banks are a reasonable distance away. This increases people’s need for resources such as water and crop security.

3. Supplemental sources of income are significant

Due to the losses farmers are facing in agriculture, many are turning to migration as a source of supplemental income. Almost half the households in the villages have at least one member who has migrated to a nearby metro city to earn a living, most often Bangalore, and sometimes Pune. The men who migrate work mainly in the construction industry during summer months, and the women work as domestic help. Many also work as agricultural labour in nearby villages, usually in the cotton and chilli farms of large-holder farmers.

Despite additional sources of livelihood such as agricultural labour and migrant remittances, supplemental income is required. However, people are not able to receive enough support through government schemes such as MGNREGA. They are also not able to secure their crops through insurance schemes.

These findings will form the basis for our plans

This data, along with the results of the aspiration study that is in the process of being conducted, will be instrumental in determining what interventions are actually desired by the communities who are receiving it.

In carrying out the socio-economic baseline, our team has gathered data for the following four sets of questions, from four different sources. The full list of questions can be accessed here.

These questions cover everything from livelihood sources and land use patterns, to regional conflicts and socio-economic structures that affect access to resources.

The answers to these questions are extensive, but critical to informing our next steps. Land degradation is a complex issue that is tied to other socio-economic and environmental concerns. Analysing this data will, we hope, help us restore the pilot site in a way that is beneficial in the long-term to the land as well as its inhabitants. We also hope it will help reduce risks of degradation in the future.

Read | The ‘Ground Truth’: Understanding Land Degradation in Raichur

Credits

The authors conducted this work when they were with the Centre for Social and Environmental Innovation at the Ashoka Trust for Research in Ecology and the Environment (CSEI-ATREE). WELL Labs is now taking it forward in collaboration with ATREE.

Banner photo: Conducting interviews with farmers for the baseline assessment. This exercise forms the basis for restoration activities in Raichur, where large parts of agricultural land is degraded. Credit: Muddurangappa Nayaka from the Prarambha team.

Edited by Meghna Majumdar.

Follow us and stay updated about our work: