Promoting Equitable Irrigation, Market Access, Agricultural Innovation, and More | Insights from the Rural Futures Programme

This blog is excerpted from WELL Labs’ Annual Report 2024–2025.

You can read the report here.

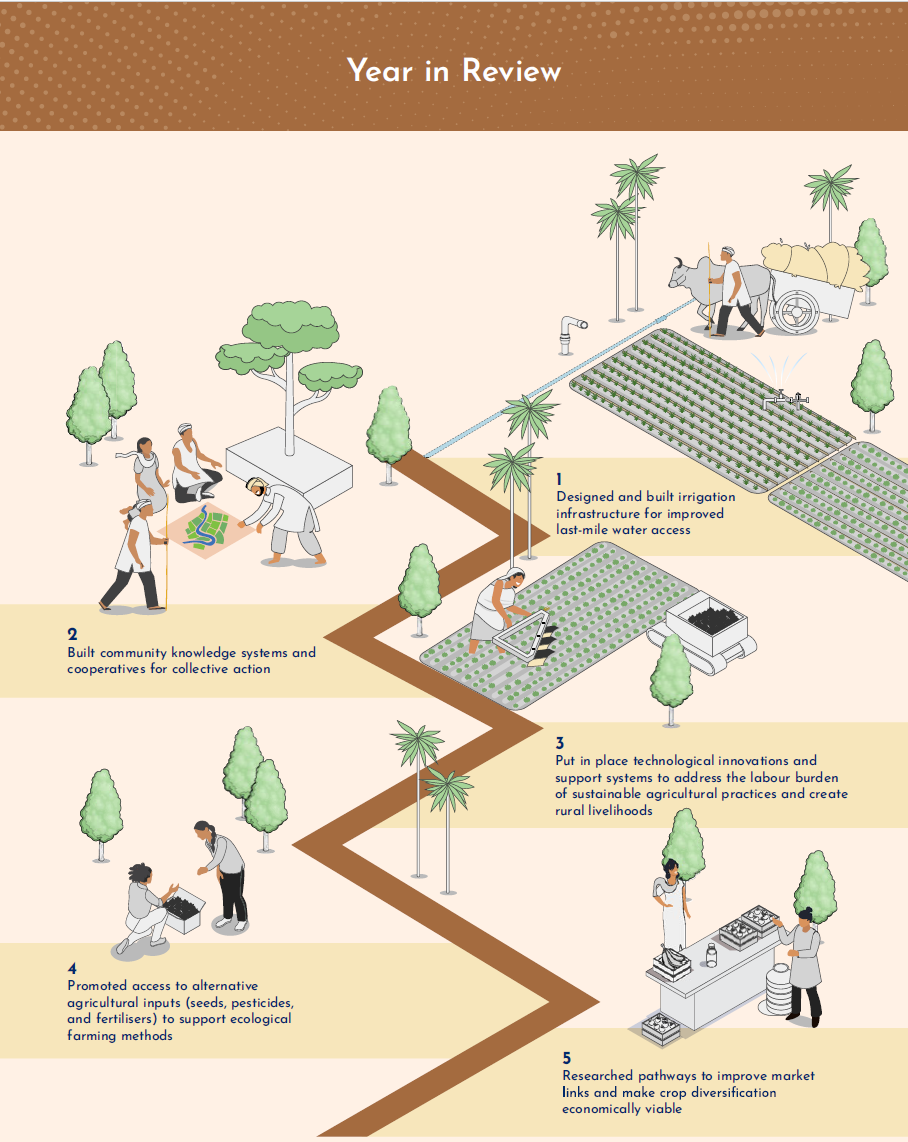

The Rural Futures programme has been working in Raichur, Koppal, and Chikkaballapur districts of Karnataka to address the interlinked challenges of unequal water access, land degradation, and low farming incomes in canal-irrigated and dryland landscapes. Over the past year, we:

- Designed and built irrigation infrastructure for improved last-mile water access.

- Built community knowledge systems and cooperatives for collective action.

- Put in place technological innovations and support systems to address the labour burden of sustainable agricultural practices and create rural livelihoods.

- Promoted access to alternative agricultural inputs to support ecological farming methods.

- Researched pathways to improve market links and make crop diversification economically viable.

Our partners include the Climate Adaptation and Resilience in Tropical Drylands (CLARITY) project, Advanced Centre for Integrated Water Resources Management, Prarambha, DCB Bank, Nvidia, IHE Delft Institute for Water Education, SOIL Trust, and Innovation Guild, among other organisations.

Illustration by Sarayu Neelakantan

Our work with our partners yielded a range of insights regarding how to make irrigation systems more equitable, promote innovation in agriculture, and boost market access for farmers, among other topics.

1. Farmers value irrigation reliability over quantity.

Many farmers at the head-end of the Naraynpur Right Bank Canal expressed interest in switching to diversified cropping systems from paddy monocultures as long as water delivery remains predictable. This is remarkable considering how entrenched the paddy-cultivation ecosystem has been in the region since the introduction of canal irrigation. Our crop diversification pilots, electronic participatory rural appraisal exercises, and irrigation planning also reinforced that farmers prefer assured water supply and control over irrigation over receiving excess water from canals.

2. Farmers are willing to invest their own money to overcome irrigation challenges.

In Mandalgudda, farmers voluntarily contributed ₹2,000 per household to revive a broken lift irrigation system. This indicates that good facilitation and trust-building can often be more critical than funding. It also highlights the confidence farmers have placed in our grassroots partner, Prarambha, and in the technical inputs regarding the design, work plan, and budgetary estimates that WELL Labs provided.

Also Read | Mapping Water, Building Ownership: A Ground-Up Approach to Water Governance

Farmers are inerested in switching to diversified cropping systems from paddy monocultures as long as water delivery remains predictable

3. Technical soundness, local ownership, and stakeholder alignment can facilitate innovation in government systems.

The ongoing pipeline pilot under Distributary 10 of the Narayanpur Right Bank Canal highlights that innovation is possible in rigid government systems. Our water-sharing initiatives come at a time when the Government of Karnataka is prioritising canal automation and pipeline-based irrigation water control. We are working with officials from two government bodies—the Krishna Bhagya Jala Nigam Limited and Advanced Centre for Integrated Water Resources Management—to ensure that policies provide an enabling environment for equitable water-sharing among head-end and tail-end farmers in canal command areas.

More recently, the Government of India approved the modernisation of irrigation water supply networks. It aims to create robust backend infrastructure for micro-irrigation, with underground pressurised piped irrigation, real-time data, and Internet of Things technologies for water accounting and management. It also seeks to handhold water user cooperative societies in managing irrigation assets.

4. Technological innovations alone cannot reduce the labour burden of agriculture.

Our study on agricultural labour revealed the two biggest sources of drudgery: manual weeding and harvesting. These tasks are physically exhausting, time-consuming, and disproportionately borne by women.

While farmers are eager to adopt labour-saving tools, they want local service providers—not distant, unfamiliar suppliers. Our pilot entrepreneurship programme showed that with basic training, community members can build viable enterprises that design, sell, rent, or repair agricultural equipment.

Thus, labour-saving innovations are not just about building or providing machines. They also involve setting up trusted local systems for access, support, repair, and entrepreneurial training.

Electronic participatory rural appraisal blends traditional participatory techniques with digital tools like GPS and satellite imagery

5. Reliable alternatives can help farmers move away from the intensive use of synthetic pesticides and fertilisers.

While many want to move away from input-intensive conventional agricultural practices, the availability of and access to alternatives remain barriers. Most local shops are dominated by paddy/cotton input ecosystems, with little support for alternative agricultural inputs.

However, only training farmers in sustainable practices is not enough to ensure the adoption of alternatives. Asking them to do the additional work of collecting environmentally friendly materials and preparing liquid manure will not show results when they can easily buy synthetic inputs from nearby stores. Instead, what works is training a separate group of service providers—landless or smallholder farmers, youth, women, etc.—to reliably produce, package, and deliver alternative inputs. However, such community input systems must rely on paid, skilled service providers rather than volunteers. Setting up bio-resource centres, that is, local hubs providing bio-fertilisers, composting solutions, and biological pest control inputs, can be helpful in this regard.

Women are especially well-suited to run these centres. Although they do the bulk of agricultural work, their contribution is often underpaid or not recognised. Bio-resource centres can provide them with steady employment, fair wages, and community recognition. The work is also rooted in their traditional knowledge of seed conservation and soil health management Many women wanted to produce alternative inputs and preserve local seeds not just for economic reasons but also to support nutrition security and long-term soil regeneration for the benefit of their families and communities.

6. Collectives can ensure that farmers get better prices for their produce.

Our journey-mapping exercise revealed that many farmers remain locked into informal credit arrangements with traders, forcing them to sell under distress. As a result, they often get poor prices for their harvest and are exposed to supply chain uncertainties. The entire system externalises risk onto farmers while limiting their control and bargaining power.

Farmer producer organisations can offer a viable alternative. They can manage aggregation, grading, and market access, and help farmers retain a greater share of the final value of their produce. Thus, market transformation requires not just better transport and storage facilities but also farmer collectives to make it equitable.

Also Read | Raichur at the Crossroads: Gender-Sensitive Strategies for Sustainable Rural Labour

Acknowledgements

Authors Ashima Choudhary, Manjunatha G, Navitha Varsha, Syamkrishnan P Aryan

Editor Syed Saad Ahmed

Published by Nanditha Gogate

Follow us to stay updated about our work.