Webinar on Water Security in Karnataka’s Small Towns: 5 Key Learnings

While Bengaluru dominated the news, this year’s harsh summer scorched towns and villages across Karnataka. A recent estimate says that the water crisis in the state has affected more than 1,100 wards and 220 talukas so far. It took a crisis to bring into sharp focus how vulnerable the state is to extreme heat and the need to build water security in a region shaped by rapid urbanisation and climate change.

Towns face unique problems. They experience the growing pains of urbanisation and population rise, while lacking the financial resources to meet new demands effectively enough. There are multiple state agencies that channel critical funds but there is limited autonomy among local authorities. In semi-arid parts of Karnataka, there remains heavy dependence on groundwater, while lack of adequate sewage treatment infrastructure pollutes lakes and surface water bodies. There are many complex and intersecting risks. How do we navigate these going forward?

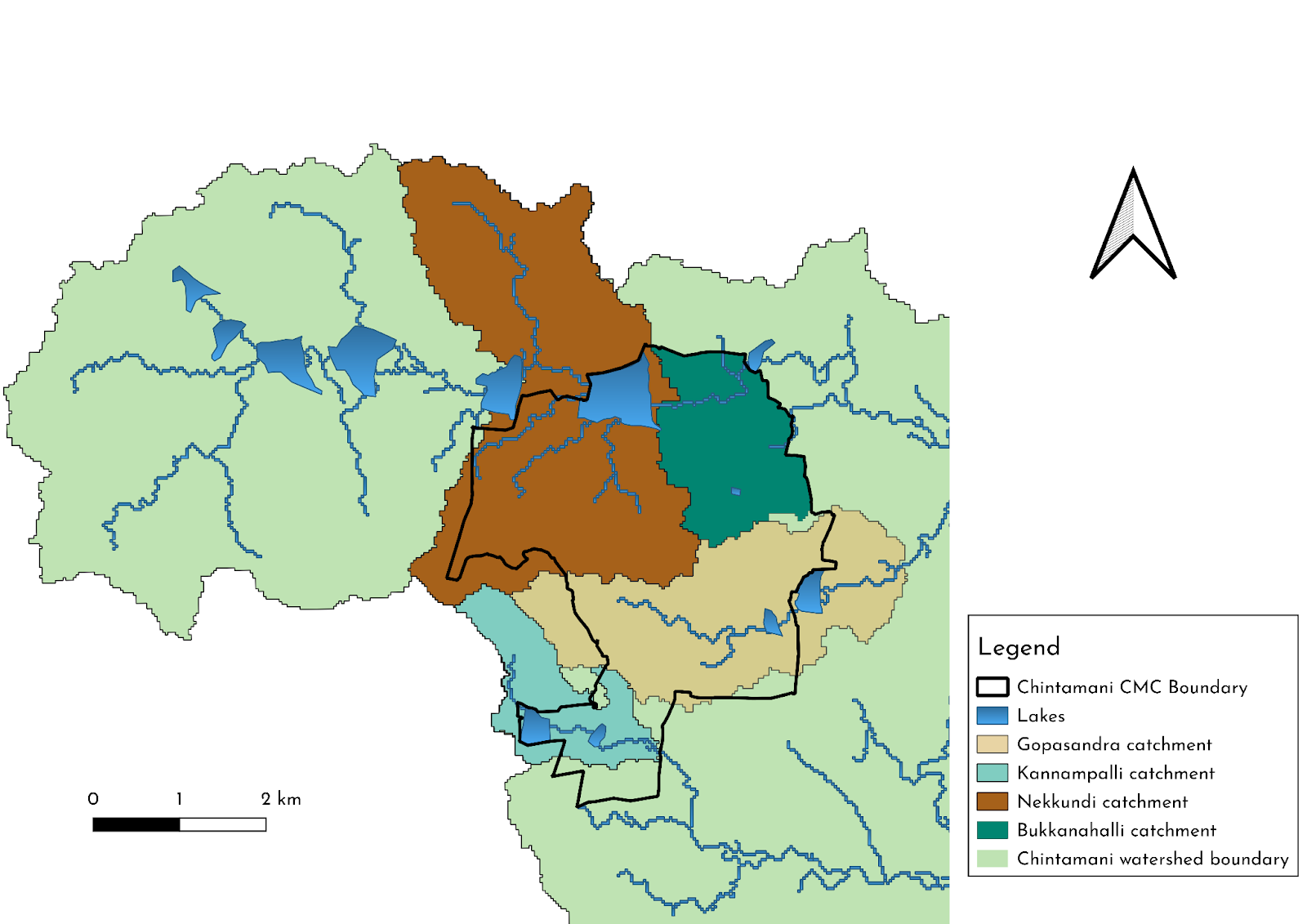

To better understand current challenges and explore opportunities for collaboration and innovation, WELL Labs partnered with Technology Informatics Design Endeavour (TIDE) and the Bremen Overseas Research and Development Association (BORDA)-South Asia to conduct a water balance study in Chintamani town.

This report is intended to serve as a critical knowledge base that will inform future strategies. We launched the report at an online convening of experts to discuss our key learnings and explore ways to improve urban water planning based on the data collected. The webinar saw a number of experts weigh in on the subject of building thriving and more water-secure towns. In this blog, we summarise five key points that came up in the discussion.

1. India is poised to experience a surge in urban water demand, with nearly 3000 small towns in the brink of obtaining statutory status with the upcoming census.

Rapid urbanisation in India has led to a sharp increase in the number of urban centres. Adding to the current number of 4,920 statutory towns, there are around 3000 census towns poised to reclassified as statutory — this could mean exponential growth in the number of small town Urban Local Bodies with the upcoming census (these categories are defined by demographic indicators such as total population, population density and the percentage of the workforce engaged in non-farming activities).

This transition demands a substantial increase in water supply, from the rural per capita standard of 40 litres per capita per day (lpcd) to 70-135 lpcd, depending on the characteristics and requirements of the towns. This necessitates huge investments in upgrading water and sanitation infrastructure. However, challenges such as depletion of water resources and the impacts of climate change further strain water supply services.

2. Water and sanitation projects in Karnataka towns are centrally governed, requiring coordinated planning among multiple agencies.

Parastatal agencies such as the Karnataka Urban Water Supply and Drainage Board (KUWSDB) play a pivotal role in planning and implementing larger water and sewerage schemes in Karnataka’s towns. This centralised governance model results in municipalities lacking autonomy as they continue to depend on state and central grants for funds, and on parastatal agencies to design and execute projects.

However, municipalities are still held accountable by residents for service delivery and bear the burden of carrying out operations and maintenance work after infrastructure is constructed and handed over.

Chintamani town grapples with water pollution, groundwater depletion and fragmented planning. Credit: Sarayu Neelakantan and Srilakshmi Viswanathan.

3. Towns continue to struggle with Operations and Maintenance (O&M)

K. Madhavi, the Commissioner In-charge of the Chintamani City Municipal Council, pointed to the fact that, in general, Urban Local Bodies have to bear O&M costs as it has to be self-sustaining but this is a huge challenge — O&M costs are high especially for water and sanitation infrastructure.

For example, in the case of Chintamani, water supply accounts for between 34% and 43% of the overall revenue expenditure. Electricity charges make up more than half the operating expenses for water supply (these numbers are sourced from the Chintamani municipality’s annual budgets from 2020 to 2023, please refer to this report for more information). Further, Non-Revenue Water loss is high, which means there continues to remain a deficit between expenditure and receipts.

4. Surface water bodies and shallow aquifer management remain key to better water resource management.

Chintamani’s water balance study showed that upto 40% of the town’s current drinking water requirements could be met through local surface water, i.e. the many lakes that fall in the region. Together with water channelled from afar, surface water bodies would recharge groundwater resulting in enough to be available during drought years. Chikkaballapur district has a history of alternating between droughts and excess rainfall every few years. K. Madhavi also mentioned that the town plans to rejuvenate Nekkundi lake while augmenting the capacity of Kannampalli lake, their current drinking water source, within the town.

Read | Lake Rejuvenation Can Resolve Urban Water Issues, But Only if Done Scientifically

Vishwanath S, Director of Biome Environmental Trust emphasised the need for understanding aquifer characteristics in hard rock regions such as Chikkaballapur district particularly the shallow aquifer. The Chintamani water balance study included a resistivity survey across the town to understand the depth and thickness of the shallow aquifer. Examples from towns near Bangalore, like Hunasamaranahalli and Devanahalli showcase the recharge potential and tapping of shallow aquifers for water provision, offering cost-effective and sustainable alternatives to deep borewells.

He also stressed on the importance of capacitating ULBs to prepare aquifer management plans under AMRUT 2.0 guidelines. Through the Atal Mission for Rejuvenation and Urban Transformation (AMRUT), cities are expected to conduct aquifer mapping with technical support from central or state agencies to identify aquifer potential and recharge opportunities, prepare a roadmap to maximise recharge potential, establish a baseline for groundwater usage and monitor the groundwater balance over time.

Recently, the the National Institute of Urban Affairs together with BIOME and other partners developed a toolkit outlining a six-step approach to managing shallow aquifers, informed by pilots in 10 Indian cities.

5. Sewer systems cannot be the magic bullet for towns

Krishna C. Rao, Advisor at the Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH) Institute, mentioned that many states that submitted City Sanitation Plans under Swachh Bharat Mission (SBM) 2.0 could not meet the cost for their own contribution (the central government’s share is 50%), pointing to a larger problem in terms of meeting financial requirements for sewer systems.

An ongoing study by the WASH Institute across nine towns in India showed that conventional sewerage infrastructure is not the only solution. A mix of approaches including partially sewered networks, decentralised sewage treatment plants, I&D (Interception & Diversion) of drains can be explored based on local conditions, availability of funds and long-term viability. They have also focused on the viability of optimising existing infrastructure. A key learning from this study has been that a ground-up study is crucial to identify cost-effective used water management systems.

Read | Bengaluru’s Wastewater Market Experiment: A Promising Solution for Water-Scarce Cities Globally

The webinar provided valuable insights about the many challenges facing India’s towns. It is critical that key stakeholders like urban local governments and grassroots communities are empowered to navigate these problems by equipping them with the resources to carry out water security planning more effectively.

All speakers reiterated the need for collaborative partnerships between government bodies, non-profit organisations and local communities to develop innovative solutions that can address infrastructure deficiencies and improve the state of people’s well-being and the environment. Such solutions must prioritise long-term sustainability, selection of appropriate technology and science-based approaches, and community engagement to ensure their needs and aspirations are met.

Read | How We Can Make Bengaluru’s Water Systems More Sustainable and Affordable

Cover Photo: View of the Malapalli lake in Chintamani, Karnataka. Credit: Ananya Revanna

Edited by Kaavya Kumar

If you would like to collaborate, write to us. We would love to hear from you.

Follow us and stay updated about our work: