A Package of Practices for Climate-Smart Agriculture

In the heart of Karnataka’s Raichur district lies Mukkanal Gram Panchayat, a region where agriculture is the main source of livelihood. Out of 203 hectares of land, almost 178 hectares are under the plough. A significant portion of this agricultural land, approximately 83 hectares, relies solely on rainwater for irrigation. The rest, though equipped with sources of irrigation like canals, wells, borewells, and stream-fed pumps, still struggle to access water.

The agricultural landscape in Mukkanal is dominated by monocropped fields of cotton, paddy, and chilli in the kharif season and pearl millet and foxtail millet during the rabi season: which is a broad mix that should ideally be enough to fulfill the community’s income, fodder and nutritional needs.

Yet, farmers of Mukkanal grapple with low yields, degraded land marred by erosion and salinity, and a paucity of agrobiodiversity, resulting in stagnating incomes.

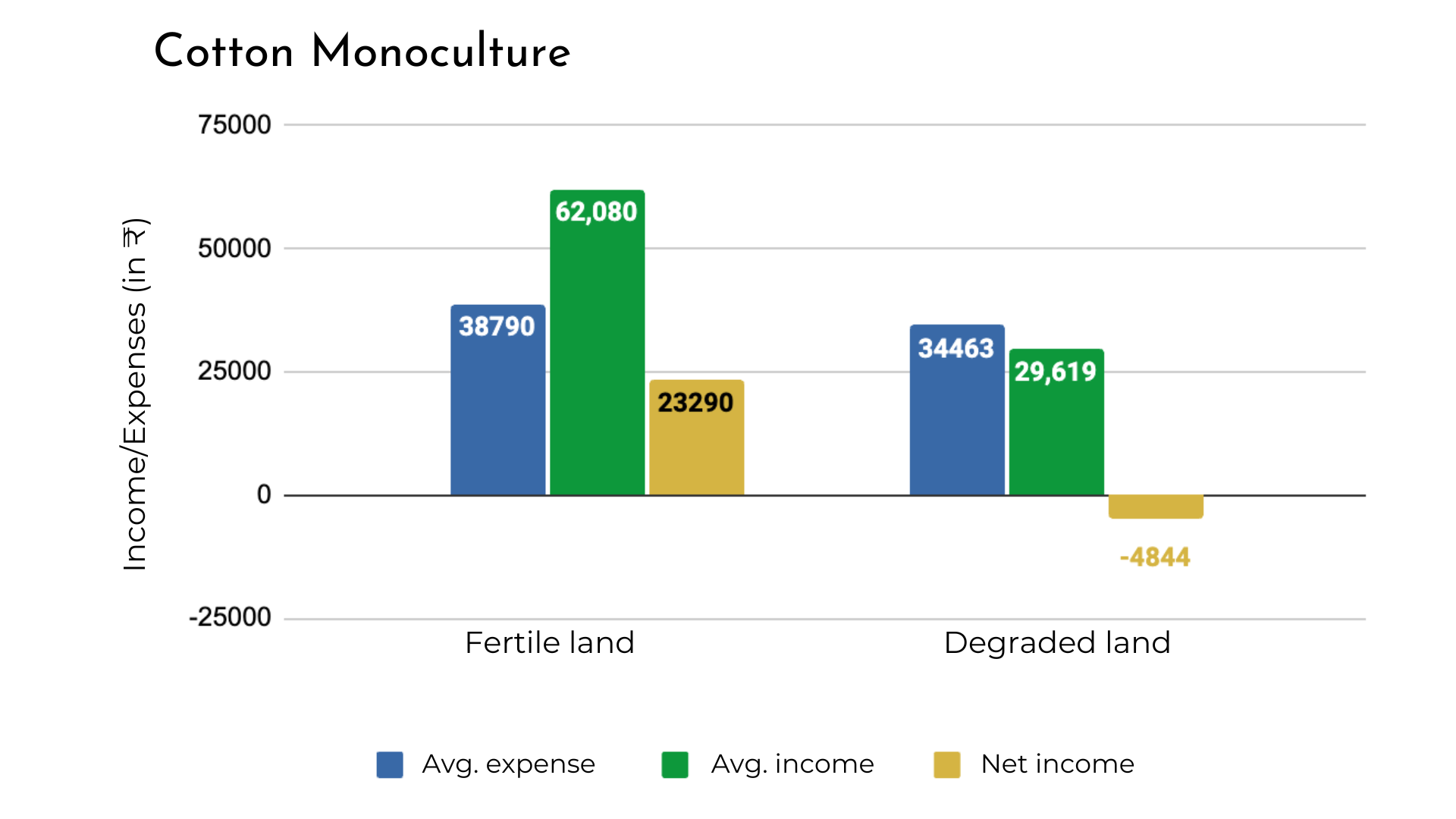

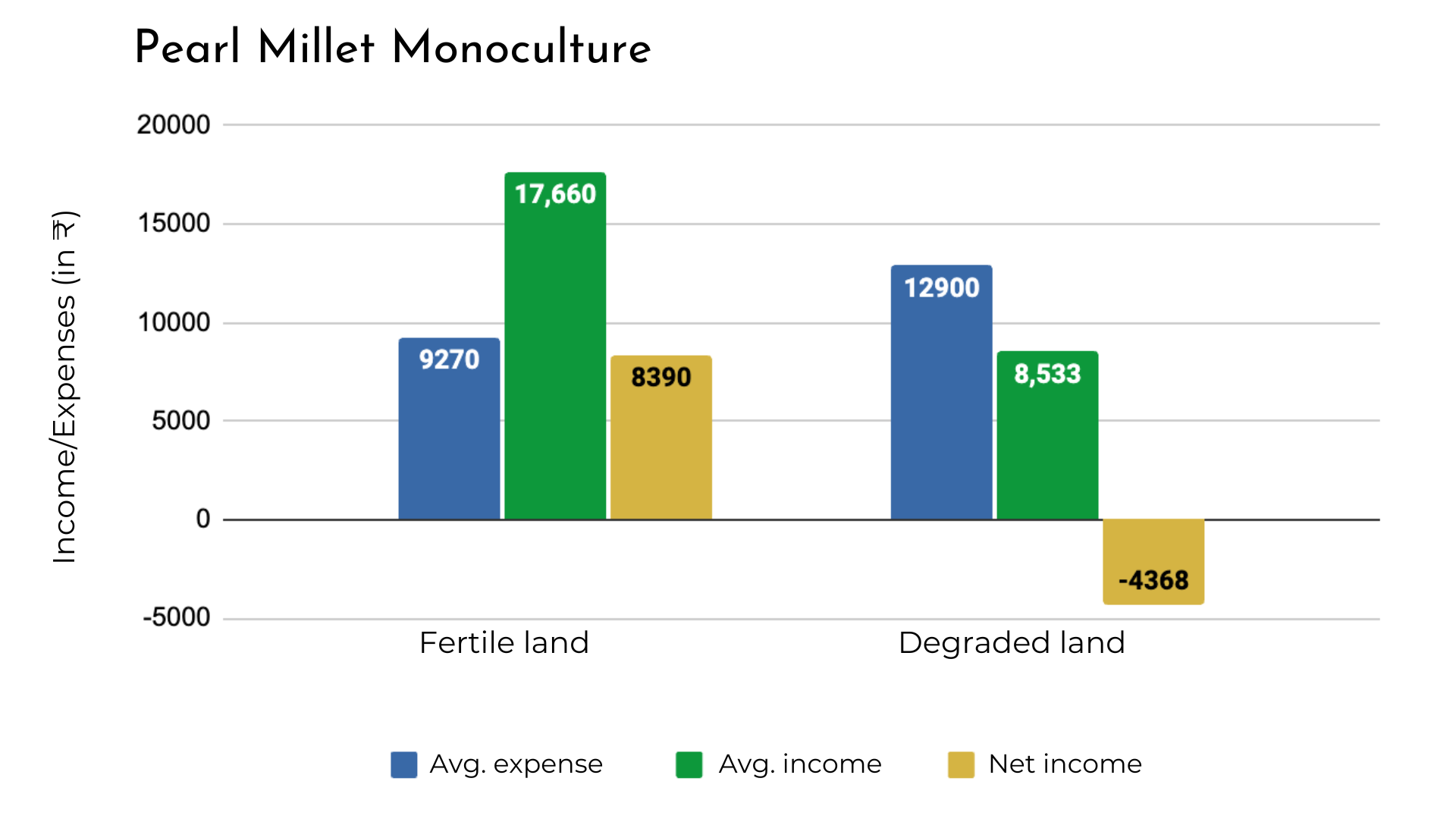

These graphs show the difference in net income between fertile and degraded land used to cultivate monocultures of cotton and pearl millet.

Over the past 12 months, WELL Labs in partnership with our grassroots partner in Raichur district, Prarambha, and the Ashoka Trust for Research in Ecology and the Environment (ATREE) have been documenting the state of the environment and socio-economic conditions in Mukkannal. We have been doing this through a series of in-depth conversations with the local farming community, co-designing and testing interventions that are best suited to the agro-ecological conditions. We call these our ‘package of practices’, tailored to the right place and right approach for restoration.

This blog delves deeper into our package of practices for the farmers, and documents our insights and learnings from the field.

Unearthing the Challenge

We first carried out comprehensive baseline assessments to fathom the root causes and types of degradation afflicting our pilot site of 1,1935 hectares across Raichur and Koppal, across five villages: Mukkanal, Parapur, Gajaldinne, Kudugunta and Malaksamudra. This involved a rigorous soil and biodiversity study, a socio-economic analysis of the farmer households in the region, and a deep dive into their aspirations and needs.

We also undertook a journey mapping exercise to visually outline the steps needed to achieve the goal of sustainable yield. It revealed an average annual income of approximately ₹1,15,475 per acre after a massive cultivation cost of ₹91,126, with a substantial 36% of the cost going to pesticides and fertilisers.

Read | Five Insights from Journey Mapping in Mukkanal

Escalating input costs have made conventional agricultural practices economically untenable for many. Which is why we zeroed in on reducing input cost for agriculture to support farmers transition to regenerative agriculture, particularly the 17 farmers who owned agricultural land within our pilot site. By adopting certain practices, such as the traditional intercropping method of Akkadi Saalu, we could help farmers to reduce input costs, thereby enabling savings and, over time, enhancing productivity per acre. This, in turn, benefits farmer households and the environment alike.

Grassroots Knowledge: Building Trust and Co-designing Solutions

Our findings, shared at a town hall meeting, initiated a dialogue on the process. Subsequently, we conducted training workshops to enable farmers to assess degradation and explore potential remedies, including locally prepared natural fertilisers like ‘panchamrita’ and a tonic for pest management known as ‘trimurthi’, and green leaves manure (GLM), specifically horsegram manure, whose impact on soil fertility was illustrated in a recent study.

P. Srinivas ‘Soil Vasu’ led these enlightening sessions, offering insights into soil particles, proportions, and quality indicators. These interactive sessions encompassed pH level testing, water-absorbing capacity assessments, evaluations of soil organic carbon, and visual soil condition assessments. These training sessions facilitated the co-design of interventions with local communities, guided by our partners at Prarambha.

Soil Vasu and Prarambha members in a meeting with farmers in Raichur. Photo by Manjunatha G.

Our proposed interventions are rooted in expert-backed scientific research and age-old agroecological principles, aimed at curbing erosion and salinity, boosting soil organic carbon and thus enhancing soil quality. The role of microbes, which account for over half of the soil organic carbon along with microorganisms and plants, plays a vital role in determining soil quality. These components significantly influence soil’s physical properties such as porosity and aggregate stability.

It was important for us to engage with farmers on this science and cultivate their understanding of soil health, its properties, and the art of soil testing.

Introducing a Comprehensive Package

In the following sections, we present the package of agricultural practices adopted by 25 farmer households in Raichur. Our approach unfolds in three stages: pre-sowing, sowing, and post-sowing, complemented by various allied activities.

A] Pre-sowing activities

To prepare the land for sowing, there are a broad range of activities that need to be carried out – from mapping farmlands and identifying degraded areas, to capacity-building for key resource persons.

Planning for sowing

- Design and conduct surveys for:

i) families, to assess their needs and socio-economic profiles, and

ii) soil, to assess the land’s ecological profile - Map extent of degradation and sources of irrigation, and design a net-plan for plots of land

- Design trench-cum-bunds (TCBs) for better water management – A bund is an embankment of soil or stones meant to control the flow of water. Depending on their purpose, bunds can be of many types, including TCBs and tree-lined bunds

- Identify, prepare and manage demonstration plots for the Gram Panchayat

- Identify and source region-specific, need-based tree saplings that are suitable to local conditions and can meet the nutritional, livelihood or other needs of the local people

- Source and distribute quality GLM seeds and facilitate testing for germination.

- Source seeds for commercial, food and fodder crops to improve soil fertility

- Arrange monitoring cards and crop calendars to document the entire process of agricultural activities, both on-farm and off farm

- Make small pits for bund plantations, for cultivating along bunds that act as dividers between farms, or on raised structures alongside TCBs.

Trench-cum-bunds, raised embankments with trenches for collecting water and preventing runoff, constructed in Raichur. Photos by Revannasiddappa.

Capacity-building for resource persons

- Establish a community bioresource centre in the Gram Panchayat for capacity building and community mobilisation purposes

- Conduct training sessions and discussions with community resource persons on roles and responsibilities related to the net-plan

- Conduct orientation sessions for the identified farming families on how to adopt diversity-based ecological farming systems and share a crop calendar for each household.

- Form Private Property Resource (PPR) groups and Common Property Resource (CPR) groups to initiate activities.

- Form crop-specific groups (Farmer Interest Groups – FIGs); schedule weekly FIG meetings to document traditional practices of farming systems, native seeds, local tree species and domestic livestock.

- Organise participation of PPR and CPR groups in Gram Sabha planning meetings.

- Network with government line departments (including agriculture, horticulture, rural development and forestry) to source various scheme-related approvals and funds.

- Initiate bio-intensive family gardening activities in each home for nutritional security. This practice was introduced independently by an external player, the BD Collaborative, and adds to the overall benefits of our package of practices. (A bio-intensive garden is one that has an inclusive mix of vegetables, green herbs and other produce, so as to meet a large portion of a family’s nutritional requirements.)

Training for farmers

- Organise training sessions on the importance of mixed cropping – the role of border crops, trap crops, nutritional crops, commercial crops and fodder crops, and how each of them can protect against crop damage, feed the soil or improve income.

- Demonstrate construction of bunds and related land-based activities.

- Demonstrate making of compost, vermicompost, improved farmyard manure, green leaves manure, liquid manures and manure/weed tea.

- Demonstrate seed germination tests and treatment.

B] Sowing and support

From this stage onwards, the farmers take the information and training provided and apply it case-by-case to their farm’s requirements. To begin with, a variety of seeds are sowed to address mixed cropping systems, taking care to decide on combinations of seeds that complement each other’s nutritional requirements without causing further imbalance in the soil’s properties. All this while the field resource persons are available to address any concerns and queries from the farmers.

Left: Mixed cropping in rows. Right: A flooded paddy field. Photos by Revannasiddappa.

C] Post-sowing activities for farmers

The work does not end with sowing. There are various measures that need to be followed to manage the growth of the crop and the soil. This is another stage where the training and demonstrations of the past few months kick in. The farmers now focus on:

- Nutritional security for growing plants through application of liquid manures once in every 20 days after sowing.

- Weed management.

- Moisture management in the farmland.

- Pest and disease management, using NPM and other techniques shown earlier

D] Allied activities

These activities are carried out simultaneously with the pre and post sowing activities. It includes:

- Source and distribute quality sowing seeds for the main and companion crops

- Explain the benefits of mixed cropping while also keeping the farmers informed on the spacing between rows and plants (border crops, trap crops and nutritional crops)

- Spread word about GLM seeds post-first rain and ploughing

- Make small pits to plant tree saplings

- Carry out post-harvest processes like sourcing and distribution of produce (for value-addition products)

Apart from this, it must be recognised that the Akkadi Saalu process produces a lot of fodder that can be used for livestock.

Farmers dry, arrange and pack harvested paddy in Mukkanal. Photos by Manjunatha G.

So, how did these steps work in practice?

This list of measures needs to be followed consistently and reworked frequently based on feedback to achieve long-lasting impact. Change is slow and iterative. But our recent visits to the pilot site showed some promising signs.

We spoke to farmers to find that those who switched to Akkadi Saalu succeeded in saving a whopping ₹3,000-₹5,000 per acre by averting pest attacks on their cotton crops.

Akkadi Saalu involves planting border crops like pigeon pea and other pulses and oil seeds which halt pests from infesting other crops. This approach is a great example of how regenerative agriculture can yield positive benefits.

While there are clear benefits to crop diversification, some farmers did share concerns of lower yield. This prompted a need to consider alternative sources of income. A farmer in Mukkanal, Kotyappa, is an example of how livelihood diversification could play a role in improving farmer incomes, as he began to tend poultry and livestock and earn better.

Read | Restoring Landscapes and Improving Farmer Income, the People-Centric Way

However, challenges persist. Access to irrigation remains a major hurdle for farmers who cultivate water-intensive crops like paddy. We are working with them help shift to alternative crops like chilli and cotton without having to face a dip in earnings.

There are lock-ins agriculture that are difficult for farmers to shift away from and it will take time and proactive support from government agencies and CSOs. The benefits and changes in mindset in such a short time indicate that the work we are doing in Raichur is on the right track and has the potential to transform the landscape and people’s livelihoods in this distressed region.

Edited by Meghna Majumdar and Kaavya Kumar

If you would like to collaborate, write to us. We would love to hear from you.

Follow us and stay updated about our work: