How Community-Led Planning Is Changing the Groundwater Story in Jhansi

A view of the landscape in Jhansi. Photo credit: Aditya Vikram Jain

Bundelkhand’s identity is shaped by its harsh climate and the enduring resilience of its people. But even this resilience is being tested. In Uttar Pradesh’s Jhansi district, various stressors have pushed water security to the brink, turning it into both a warning and a lesson for the rest of Bundelkhand.

Despite receiving an average of 846 mm of rainfall each year, Jhansi’s water reality remains grim. Erratic monsoons, frequent droughts, and a deep dependence on its hardrock aquifers keep the ground persistently dry. Large reservoirs like Parichha and Matatila offer some relief, but the district still relies heavily on groundwater, extracting roughly 70% of what nature can replenish. While Central Ground Water Board (CGWB)’s official classifications label Jhansi as ‘safe’, its hardrock aquifers tell a different story: they recharge slowly, drain quickly, and are easily overexploited.

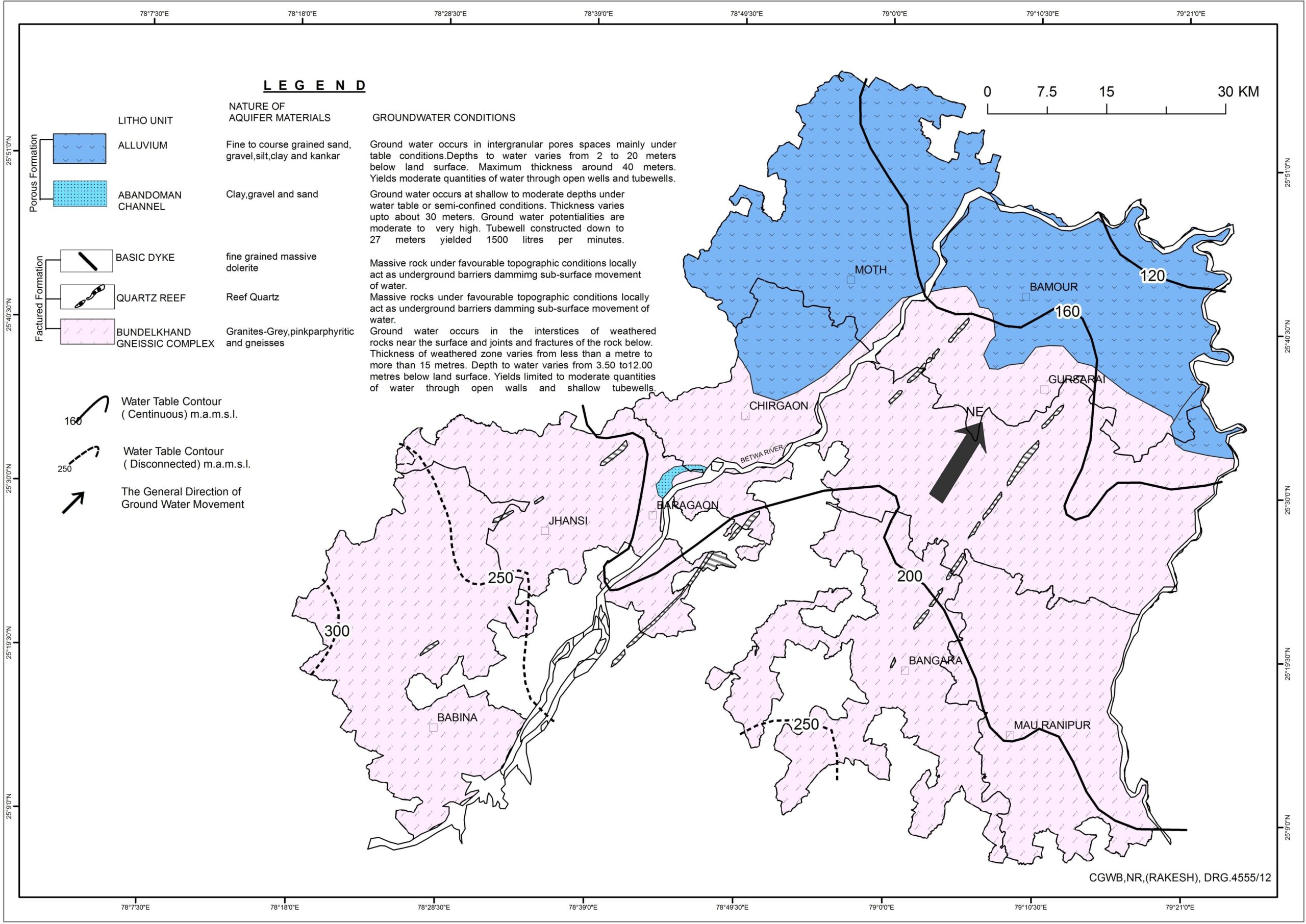

This fragile geology directly affects farming – the backbone of Jhansi’s communities. Most aquifers lie in thin weathered or fractured layers, with water-bearing zones usually within just the top 40 m. The northeast-southwest alignment of the quartz reef ridges in the Bundelkhand craton further block underground flows, creating patchy pockets of water. In addition, poor soil infiltration (as low as 4 mm per hour) causes monsoon rain to run off instead of percolate into the ground. As a result, even a year with 60% above-normal rainfall can leave wells unreplenished. With 90% of Jhansi’s groundwater going to irrigation, farmers feel this stress most deeply.

A visual representation of the hard rock aquifer and water flow systems in the region. There is some variability in water infiltration in Bundelkhand, with the region in pink (hard rock system) seeing poorer rates of infiltration than the blue (alluvial system). Source: CGWB

Creating a Sustainable Future With the Community

Amid these challenges, participatory water management is emerging as a way forward. When communities understand their aquifers, monitor wells, and plan recharge structures collectively, they can manage scarce groundwater more sustainably.

Read More | Measuring What Matters: Communities Assessing Water Solutions

This is precisely the shift that the Atal Bhujal Yojana (ABY) has brought since its rollout in Jhansi in 2020-21. The programme blends science, data, and community behaviour, empowering gram panchayats to prepare water security plans using CGWB data, rainfall records, and local well surveys.

During our visit to a few GPs in Jhansi as part of a learning study of the ABY, we saw that community participation in groundwater budgeting, use, and conservation was both widespread and deeply embedded in village processes. This strong engagement is closely linked to how ABY is implemented on the ground. Under ABY, villages themselves identify demand-side practices such as micro-irrigation, along with supply-side measures like check dams, farm ponds, and rainwater harvesting structures. Flow meters and digital water-level recorders help them track actual groundwater use, and performance-based incentives further encourage water-saving actions. Together, these elements create a framework where communities not only discuss groundwater issues but also actively plan, monitor, and adjust their behaviour to manage the resource more sustainably.

A checkdam was constructed in Dhikauli, Jhansi district under the ABY scheme to help groundwater recharge. Photo credit: Aditya Vikram Jain

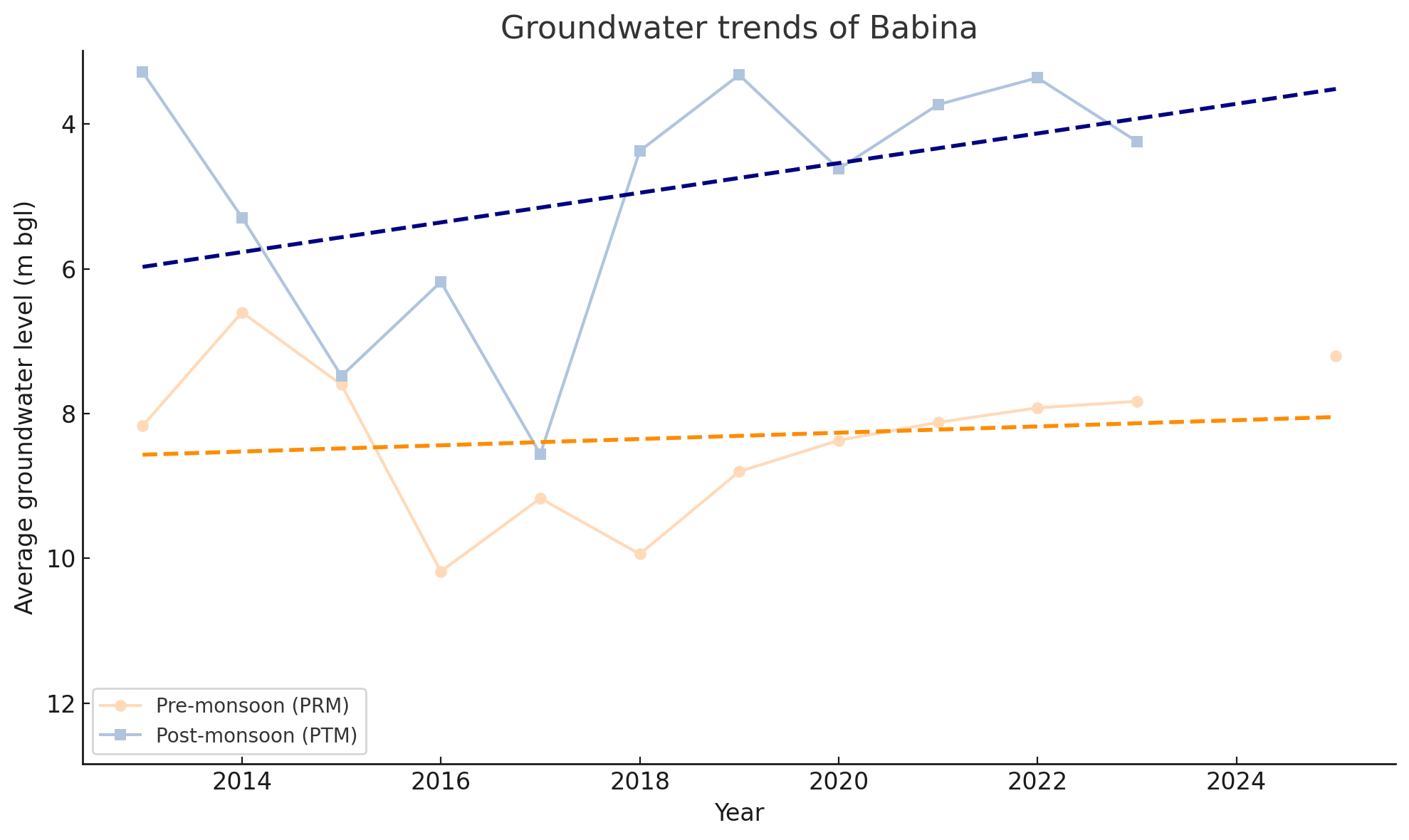

Our fieldwork revealed that the scheme’s impact is starting to take shape. Farmers like Ram Bihari from Mauranipur, who adopted protected cultivation and drip irrigation, have saved water while improving income. In Dhikauli village, Babina block, a long-demanded check dam built in 2023-24 has already helped reverse declining water levels, allowing farmers to irrigate two crops a year. Across Babina block, the rate of groundwater decline has slowed notably after 2020, unlike in non-ABY blocks such as Bamaur, Gursarai, and Chirgaon, where rate of decline continues to rise.

Groundwater trends in Babina show that its pre- and post-monsoon levels generally improved during 2014-2020, and stabilised in 2020-2025. Source: Author’s analysis using SGWD data

The Way Forward

Semi-arid regions like Jhansi can benefit from similar community-driven, data-linked approaches to sustain their water futures. Participatory groundwater programmes are essential to support communities as they navigate these challenges, ensuring they have both the knowledge and the tools to manage their resources sustainably. Though difficult aquifers and unpredictable rains shape the landscape beyond our control, resilience becomes possible when communities plan together, monitor their groundwater, and adopt efficient water practices.

Acknowledgements

This work was conducted as part of a learning study of the Atal Bhujal Yojana, and is supported by Arghyam, Water for People, and Environmental Defense Fund.

A special thanks to Manish Kumar Kanojiya, DPMU Nodal officer, ABY Jhansi and the team at WELL Labs conducting the study: Karan Misquitta, Zahra Afreen and Vivek Grewal.

Authored by Aditya Vikram Jain

Edited by Ananya Revanna

Published by Nanditha Gogate

Follow us and stay updated about our work: