How Water Shapes the Lives of Farmers in Raichur: Field Notes from Mandalgudda

When you look at a map of Raichur, you find a district flanked by two major rivers – the Krishna and Tungabhadra. Along with Koppal and Bellary districts, this region in north Karnataka is even called the ‘rice bowl’ of the state. Based on this information alone, you would expect a fertile landscape where farming thrives and access to water is unfettered. But this is far from the case.

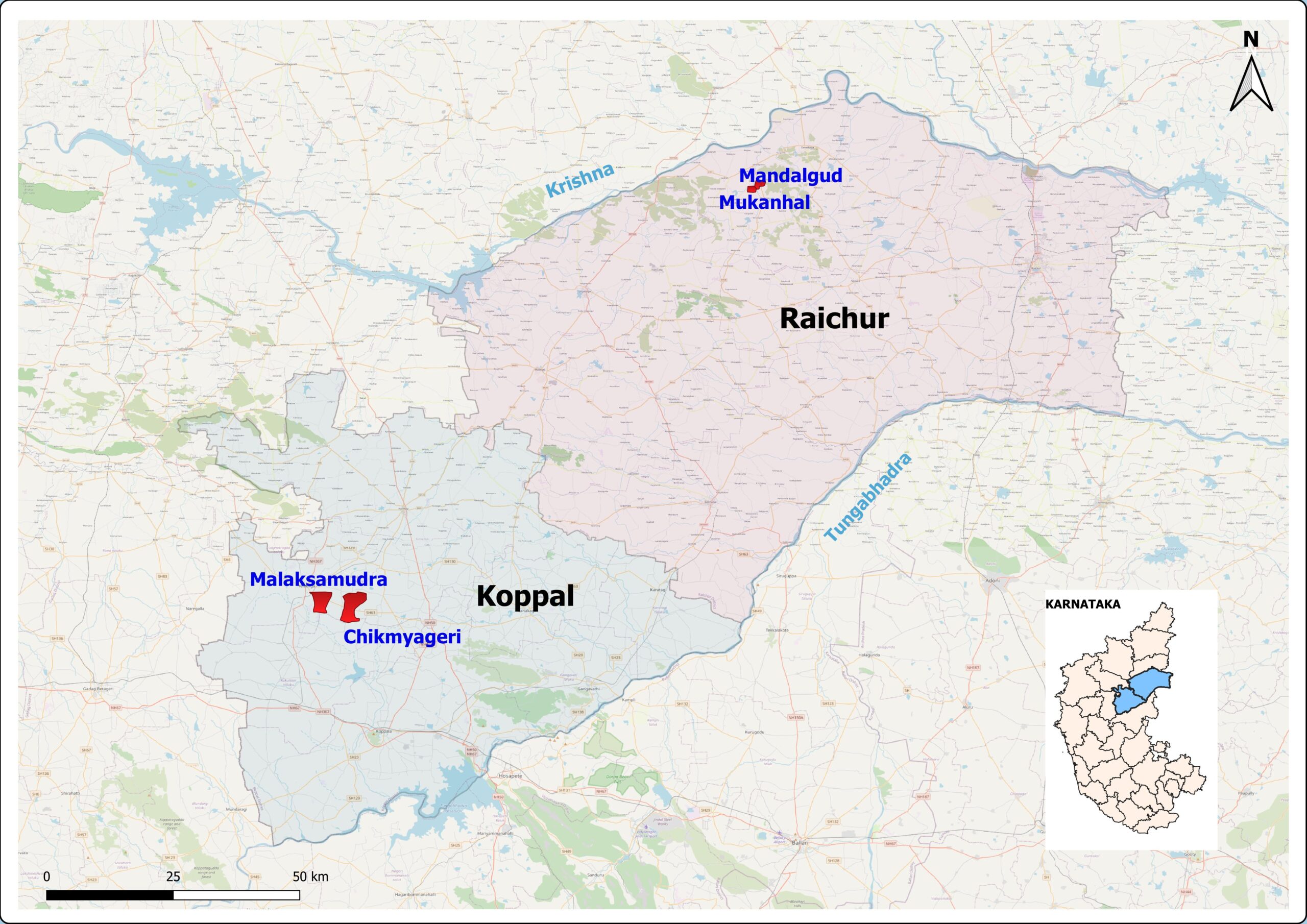

We conducted a survey in four villages in Raichur and Koppal districts. Map: Vidhyashree Katral

Raichur is a place where there’s a ‘visible paradox of lush fields of rice, cotton, and chilli alongside rampant distress migration’, low nutritional security and poor healthcare infrastructure (Karishma Shelar wrote about this for Revolve). Over the past two years, we have been visiting different parts of the district to study what’s driving such high levels of impoverishment, specifically how farming households are impacted, what they aspire for and how they cope with worsening land degradation, erratic weather and market conditions, and social and economic fissures. The different strands of our analyses reinforced a known fact of life in the region – that water shapes decisions and livelihoods. Inequities stem from access to water as those who are rainfed struggle to cover their agricultural expenses and are mired in debt.

They are also far more likely to migrate. Those who have access to irrigation are able to earn more because they have a reliable source of water and are less likely to face crop loss. The difference in net income levels between the two groups is stark.

One of these studies was a journey mapping exercise – a methodology that helps visualise the steps that an actor takes to reach a goal. Each task or activity is placed on a timeline, different stakeholders are mapped out, outputs are listed and – most importantly – ‘pain points’ or challenges are identified. We recently conducted a journey mapping exercise with 65 farmers in Mandalgudda and Mukkanal villages of the Devadurga taluk in Raichur.

Read | Part 1: Journey Mapping to Plan the Future of Mukkanal’s Farmers

Focus group discussions with women farmers in Raichur as part of a journey mapping study that WELL Labs is conducting. Credit: Suresh Gowda

One of these farmers was Yelanna (name changed), who paid Rs. 20,000 to lease one acre of land to grow cotton, a cash crop commonly cultivated in northern Karnataka. He is now in debt of Rs. 12,500 because the money he put into his fields was higher than what he earned from it, ‘I have to buy seeds every time, buy fertilisers, pesticides. I also have to depend on the rain. I have six mouths to feed; how will people like me survive if some of us don’t move to cities in search of work during the summer.’

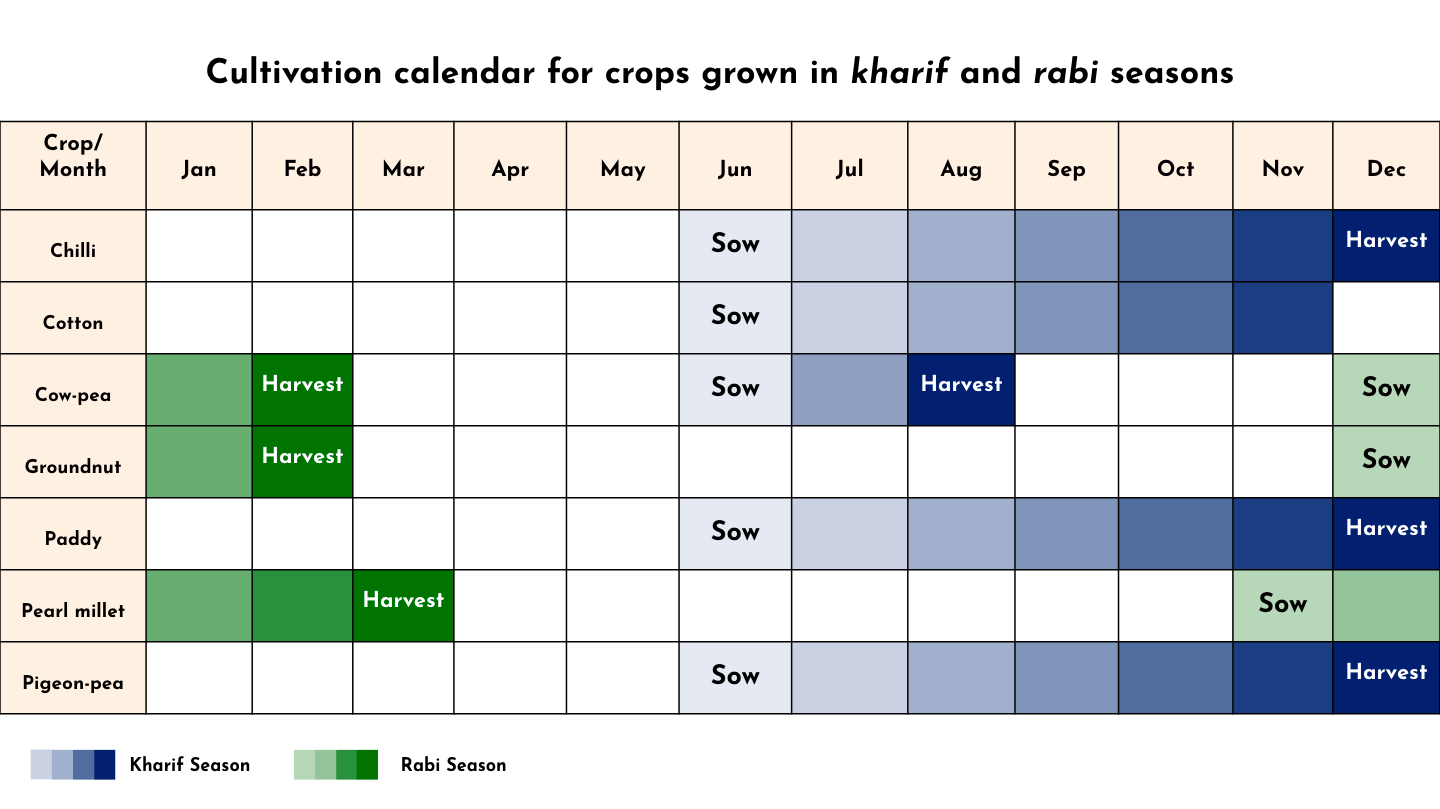

Yelanna is from Mandalgudda village where he grows cotton during the kharif season (monsoon) and leaves the land fallow during rabi (winter). His story is not the exception but the rule among rainfed farmers.

Farmers without irrigation access are going into debt and forced to migrate.

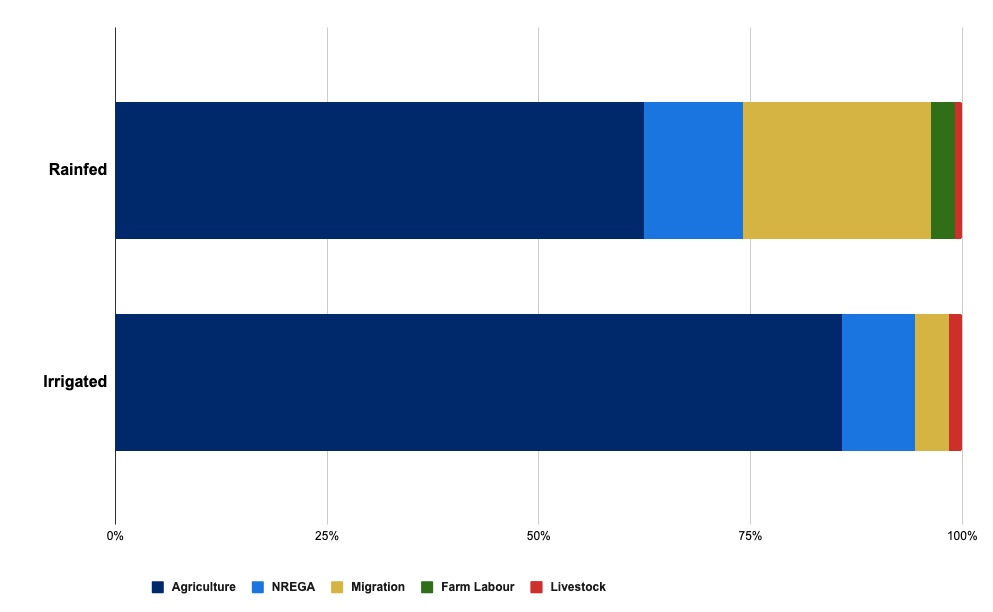

Through focus group discussions and interviews, we gathered that the average net agricultural income for rainfed farmers is Rs. -20,718 per acre/season and for irrigated farmers is Rs. 18,124 per acre/season. The negative figure indicates that these farmers are struggling to earn enough to even make up what they spent on farm inputs such as fertilisers. While the costs of inputs remain high, they continue to harvest a low yield, forcing them to look for other sources of income – the graph below shows that the most common alternatives are employment in cities or wages earned through the National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (MGNREGS).

Rainfed farmers cannot rely on agriculture alone for income. They migrate or turn to NREGA work for income to sustain their households. Irrigated farmers are more secure.

The average net agricultural income (Rs. 18,124) for irrigated farmers suggests their yields and income are sufficient to cover expenses and potentially generate a profit. The deciding factor is clearly water.

We also spoke to farmers about the loans they take to sustain their livelihoods. The average loan among rainfed farmers is Rs. 71,273 and for irrigated farmers, it was significantly higher at Rs. 1,77,034.

From this, we gleaned that rainfed farmers rely on loans to cover basic needs such as access to more land or inputs such as fertilisers and pesticides. But these lower figures, as compared to irrigated farmers, do not shield them from cycles of debt because they barely earn enough to pay back.

The much larger average loan amount for irrigated farmers indicate several possibilities such as higher input costs and the fact they cultivate over two crop seasons.

So, what do these figures mean? The journey mapping method allows us to scratch the surface of cold data and get a fuller picture of how people respond to these circumstances. This qualitative information is vital to shape interventions in a bottom-up manner, keeping their needs and concerns central.

Most rainfed farmers told us that they seasonally migrate to Bengaluru or Mumbai or even small urban centres in Karnataka and Maharashtra to work at construction sites. We also encountered many women who travel in overcrowded auto rickshaws to larger fields where they work as labourers harvesting cotton for an average pay of Rs. 200 per day. Some of the larger households we visited told us that they delegate a range of tasks from tending to their own farm, working in others’, caring for children and domestic chores such as cooking and cleaning.

We observed how the community takes decisions and come together for festivals

We spoke to farmers to ask what crops they sow and why. ‘We don’t have any specific crops in mind. If we see that someone has made good profits growing a particular crop, we discuss and decide to grow it as well,’ says Malamma (name changed). Among the crops harvested in the village are maize, groundnut, cotton and bengal gram. Based on our conversations, we compiled this crop cultivation calendar in the region:

Besides growing crops, most families owned some farm animals – ox, goats, cows, hens. Pearl millet (ಸಜ್ಜೆ read as sajje) crop residue (straw) was the main cattle fodder that was either collected from their own fields or purchased. (Pearl millet doesn’t require much water or fertilisers, making it suitable for the region.)

The routines in Mandalgudda are dictated by power cuts and the weather. People also change their routines based on weekly markets (ಸಂತೆ read as Sante) and yearly fairs (ಜಾತ್ರೆ read as Jātre); some are much awaited and occur once every five years. When we visited the village in December 2023, the village was clearly anticipating one such fair within the next few weeks. The festive atmosphere was palpable – homes were being white-washed and painted; goats being well fed in preparation for the fair; and relatives from other villages were being invited to stay over for the three-day long celebrations. In the midst of those preparations, regular work continued as usual.

There is a nostalgia for older farming techniques like Akkadi Saalu.

Some of the elderly farmers recounted stories of how, when they were children, a multi-cropping technique called Akkadi Saalu, was the norm. They described how tasty their grains were and the ease of having access to fresh vegetables and never being so worried about money.

In their view, things changed, particularly cropping patterns, with the influx of hybrid genetically-modified seeds and the onset of access to water through large-scale irrigation projects that fed water from rivers through a network of canals. This fuelled inequitable distribution of water with head-end farmers, those closer to the source of water, getting more water than they need and prompting them to switch to water-intensive crops such as paddy. This resulted in one group earning far more, while tail-end farmers and small and marginal farmers dependent on the rain saw their income stagnating.

Illustration by Aparna Nambiar. This graphic represents two scenarios. On the left, as the animation starts, we see head-end farms (closer to the reservoir or source of water) cultivating water-intensive crops like paddy. Tail-end farms, towards the bottom right of the image, are left with too little water to cultivate. But a shift to more sustainable cropping patterns like groundnut, cotton and chilli would ensure more equitable distribution.

Rainfed farmers saw their irrigated counterparts enjoyed significantly higher yield from cultivating fields of paddy and aspired to shift from Akkadi Saalu themselves.

While access to water opened up more opportunities and increased farmers’ incomes, it also led to challenges such as increased input costs. A once-rainfed farmer may have been able to shift from Akkadi Saalu, which is less water-intensive, to monocropping of paddy that fetched more income in the short-term.

However, these profits waned over time because monocultivation demands more inputs and results in lower yield over time as the land degrades due to excessive use of chemical fertilisers and chemicals.

The new seeds also meant that farmers could no longer regenerate seeds for the next cycle, rather they needed to buy these from the market at the start of every season – yet another expense. The farmers also spoke to us about how the use of cattle dung declined as many saw unimaginable yields with the initial usage of synthetic fertilisers. The shift is so stark that the newer generation of farmers balk at the thought of handling dung with bare hands, but are accustomed to the fumes of chemical fertilisers they handle.

Water is central; we need to focus on ways to ensure access to water.

These are only a few anecdotes from our time on the field. We are systematically documenting the breadth of quantitative and qualitative data we gathered through journey mapping. Totally, we have interviewed 91 farmers across four villages in Raichur and Koppal (see map at the start of the article) giving us insights on the extent of land degradation and how it’s impacting the most marginalised communities in the region. It also sheds light on adaptation measures that could help them shift to more financially remunerative and ecologically sustainable pathways.

Given the centrality of water, the Rural Futures initiative at WELL Labs is studying how this can be an entry point to improve people’s lives, i.e. how protective irrigation infrastructure – both physical (canals, tankers, pipelines) and social (water-user groups) – can be implemented to ensure rainfed farmers are able to get that essential supply during dry spells to prevent crop failure. These small amounts of water for protective irrigation in the kharif season and enough soil moisture for a second crop during rabi to grow fodder or groundnut or other short duration crops, could haul marginal rainfed farmers out of this cycle of debt through better yield and thus higher incomes.

With inputs from Ashima Chaudhury, Syamkrishnan P. Aryan and Kaavya Kumar. All our fieldwork in Raichur is facilitated by our grassroots partner, Prarambha.

If you would like to collaborate, write to us. We would love to hear from you.

Follow us and stay updated about our work: