Transforming Rainfed Agriculture with Groundwater Collectivisation

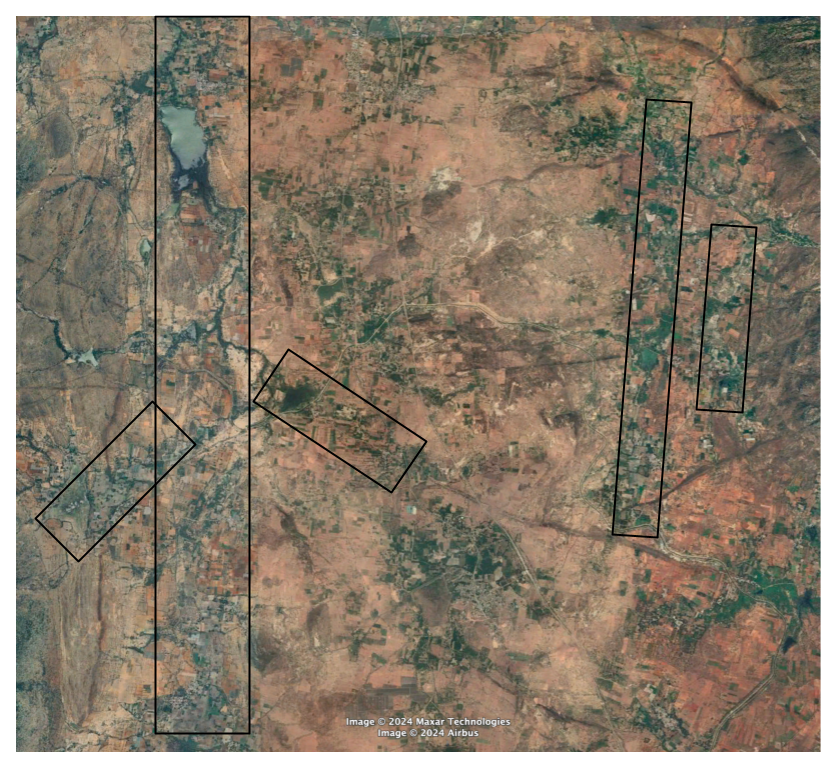

An aerial view of Anantapur. Photo credit: Manram Collective

This is the first installment of a two-part blog series detailing our findings from a monitoring and evaluation study of WASSAN’s groundwater collectivisation programme.

In India, nearly 60% of farmers rely on an increasingly erratic and unpredictable monsoon to grow crops, with dry spells posing a severe threat to rainfed agriculture. Climate change exacerbates this vulnerability, as there is a significantly increasing trend in the annual frequency of dry days during monsoons. This is especially true of the central part of southern India—including parts of Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Karnataka, and Tamil Nadu—which is the country’s second driest region after the Thar Desert.

In this region, farmers tend to have better crop yield and income if they have borewells, as they won’t entirely be dependent on the monsoon. Borewells enable a second productive cropping season and offer a buffer for monsoon crops during extended dry spells. It is, however, a common misconception that owning a borewell is the same as owning the water in it. Over the years, the growing number of borewells has led to a race for increasingly scarce groundwater. Farmers are incurring higher expenses as they dig deeper, often with little yield.

Recognising groundwater as a shared resource that requires equitable and sustainable use, the Watershed Support Services and Activities Network (WASSAN) launched the groundwater collectivisation programme in 2007. Aimed at revitalising rainfed agriculture, it promotes a cooperative approach to managing scarce groundwater. The intervention has been taken up by 73 villages in Telangana and the Rayalaseema region of Andhra Pradesh.

WELL Labs and Environmental Defense Fund (EDF) are conducting a monitoring, evaluation, and learning (MEL) exercise to assess the socio-hydrological impacts of the programme. This article explores the programme’s approach to groundwater management, especially in relation to the region’s hydrogeology, and its benefits to farmers.

The Role of Hydrogeology in Climate Resilience

This semi-arid region, infamous for erratic rainfall, faces significant challenges due to both its climatic and hydrogeological conditions. Its granitic hard rock aquifers store limited water in the top two hundred metres and none in the rocks below because of low porosity and permeability, leading to a lack of natural water resilience.

Unlike the large alluvial aquifers of the Indo-Gangetic Plains, where over-extraction causes a gradual decline in water levels, the smaller granitic aquifers seasonally oscillate between two extremes—parched summers and quenched monsoons. To put it simply, alluvial aquifers are like bathtubs, where water levels decline slowly, and granitic aquifers are like egg cartons, drying up quickly in isolated pockets. A couple of years of poor rainfall can cause wells to dry up in such low-storage aquifers.

Smaller aquifers are more conducive to participatory groundwater management because they can be managed by the few villages that form the watershed, which is what WASSAN is attempting to do through its water user groups (WUGs). In contrast, alluvial aquifers may span vast and diverse regions, requiring coordination across multiple communities, which presents distinct challenges for sustainable management.

In addition to these hydrogeological challenges, the region’s geography plays a key role in agricultural practices. In peninsular India, valleys traditionally support irrigated agriculture due to better groundwater storage in weathered geological formations. In contrast, there is less weathering in the uplands and the water drains downstream quickly, limiting the potential of wells and restricting farmers to a single rainfed crop in monsoon. This uneven access to irrigation further exacerbates the challenges farmers face of the upland farmers. WASSAN’s programme attempts to overcome this hurdle through its underground pipeline network.

In Rayalaseema, agriculture is more prevalent in the valleys, highlighted by black rectangles, because of access to irrigation.

The crops in the photo are irrigated by water that’s transported by pipes from a nearby valley in Anantapur, Andhra Pradesh. Photo credit: Vivek Grewal

Understanding the Groundwater Collectivisation Programme

The groundwater collectivisation programme aims to raise awareness about groundwater management through two primary approaches. First, it supports villages to form water user groups comprising borewell and non-borewell farmers in contiguous land patches. Second, it helps build underground pipeline networks in these lands to expand irrigation.

The programme aims to benefit borewell owners by improving water access to distant plots and reducing water losses, and non-borewell owners by ensuring access to protective irrigation during the kharif season.

Building Resilience Through Water User Groups

As members of the water user groups, farmers must commit to not drill new borewells for at least 10 years to curtail competitive drilling and reduce the risk of borewell failure. To ensure accountability, transparency, and sustainability, the agreement is formalised in the presence of a local administrative official. Other provisions of the agreement include:

- Reducing the cultivation area of water-intensive crops, like paddy, by 50%.

- Promoting intercropping or mixed cropping to ensure resilience against market and climatic fluctuations.

WASSAN also provides the groups access to subsidised micro-irrigation systems, like drip and sprinkler systems, and offers training on crop water budgeting to encourage better crop selection and water-saving practices, such as mulching.

Expanding Irrigation Through Pipelines

Through the water user groups, villagers identify contiguous land parcels to create an underground pipeline network. At scheduled times, borewell owners release water into the network, ensuring shared access to the community. This system not only transforms rainfed farmlands into irrigated ones but also addresses the challenges posed by fragmentation of land in the region. Both borewell and non-borewell owners benefit: non-borewell farmers gain access to protective irrigation, while borewell owners can irrigate their plots far from their borewells.

WASSAN subsidises the cost of installing the pipes in exchange for a legal agreement from the farmers to adopt more efficient water use practices.

Overall, the initiative is aimed at lessening competitive drilling, reducing dependence on water-intensive crops, and promoting sustainable groundwater management.

Insights from the Monitoring and Evaluation Study

WELL Labs and EDF are partnering with WASSAN to evaluate the groundwater collectivisation programme. The assessment examines its impact and identifies factors influencing scalability. Similar initiatives could benefit communities and the environment across the country.

The data collection and analysis for the evaluation are underway and the findings of which will be out soon. Stay tuned!

Authored by Vivek Grewal, Abhishek Das and Gopal Penny

Edited by Ananya Revanna and Jonathan Seefeldt

Published by Ananya Revanna

If you would like to collaborate, write to us. We would love to hear from you.

Follow us and stay updated about our work: