Improving Decision-Making in the Water Sector | Insights from the Technical Consulting Programme

This blog is excerpted from WELL Labs’ Annual Report 2024–2025.

You can read the report here.

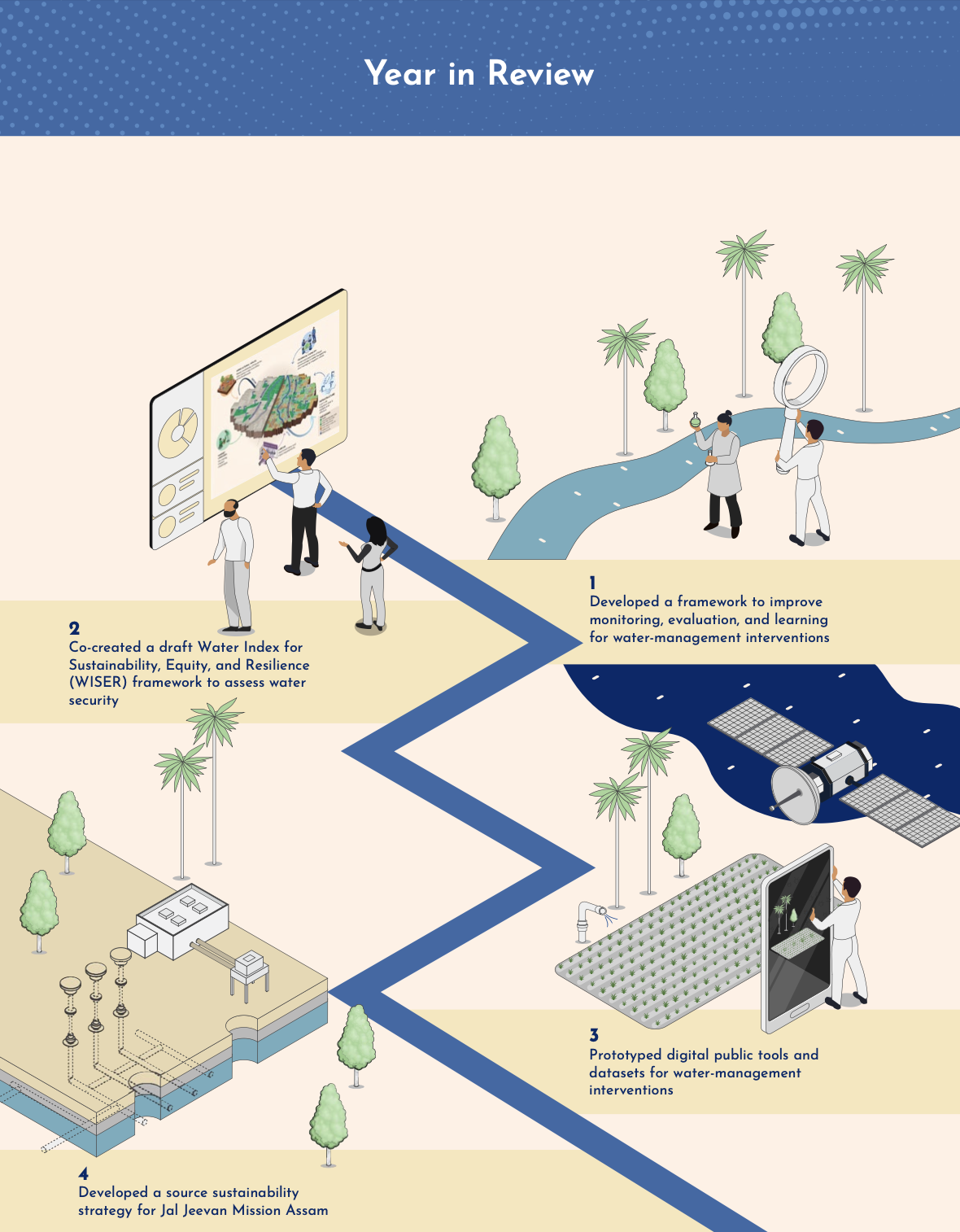

The Technical Consulting programme enables better decision-making in the natural resources management sector through data and tools. Over the past year, we:

- Developed a framework to improve monitoring, evaluation, and learning for water-management interventions.

- Co-created a draft Water Index for Sustainability, Equity, and Resilience (wiser) framework to assess water security.

- Prototyped digital public tools and datasets for water-management interventions.

- Developed a source sustainability strategy for Jal Jeevan Mission Assam.

We partnered with various organisations for these initiatives: Environmental Defense Fund, Save Groundwater Foundation, WASSAN, Arghyam, Foundation for Ecological Security, Tata Consumer Products Limited (TCPL), Aga Khan Foundation, Aga Khan Rural Support Programme (India), MS Swaminathan Research Foundation, Indian Institute of Technology Delhi, CommonsTech Foundation for Participatory Technologies (CFPT), Asian Venture Philanthropy Network, Public Health Engineering Department, Assam.

Illustration by Sarayu Neelakantan

Our work with our partners shaped the following insights:

1. High-quality evidence regarding what works in water management is often expensive and slow to produce.

This hinders government agencies and civil society organisations from adopting evidence-based strategies. Our Monitoring, Evaluation, and Learning (MEL) Toolbox seeks to overcome this challenge by democratising the process of evidence generation with user-friendly, modular tools for impact assessment. The toolbox includes:

- Playbooks for better on-ground monitoring of interventions.

- Intuitive web and mobile applications that allow both experts and novices to assess interventions using remote sensing and participatory field data.

2. We must focus on the most common interventions in the sector first, before assessing newer ones.

The watershed management sector in India is quite mature and has developed a set of common supply-side and demand-side interventions. However, these interventions may not be applicable in all locations. Scientific assessments for their applicability, site suitability, and impacts have not been adequate. Besides, the quantitative and social benefits of these interventions are often quoted through unrepresentative secondary literature.

What we need instead is in-situ continuous monitoring of a representative sample of these interventions. Thus, to cover the largest ground and ensure the optimal use of limited resources, we should focus on assessing the most common interventions first.

Also Read | How Can We Measure Water Security Accurately?

To ensure the optimal use of limited resources, we should focus on assessing the most common water management interventions first

3. Groundwater interventions often fail not because of poor implementation but because they were misdiagnosed or misaligned with local hydrological and socioeconomic realities.

Groundwater-recharge interventions are most apt for places where the aquifer’s water storage volume is greater than the natural recharge. There are large swathes in the country where post-monsoon water storage is limited due to shallow aquifers. Since natural recharge quickly fills these aquifers, additional recharge interventions are not needed (as was the case with the groundwater recharge structures we evaluated in Jalna district).

In low-storage areas, demand-side interventions may be more suited than groundwater-recharge interventions. Similarly, in regions with irrigation from dams and reservoirs, demand-side interventions such as micro-irrigation work better as they may have a larger impact on water savings. Outside canal command areas, supply-side interventions, such as percolation tanks and trench-cum-bunds, are more suitable.

Thus, diagnostics on the problems in a given area and the most appropriate solutions to address them are important to ensure that money is spent in the most efficient way.

4. To achieve impact at scale, organisations must work closely with government stakeholders, who are uniquely positioned to influence systemic changes in the water sector.

The government is the largest actor in India’s water sector, with unmatched reach, regulatory authority, and access to data. While the Technical Consulting team has focused primarily on issues like recharge and aquifer sustainability, impact at scale requires equal attention to demand-side management, water allocation, and water governance—domains where the government is extensively involved.

Our field-based insights and evidence can play a valuable role in improving the design and targeting of government programmes by highlighting ground realities and adaptive strategies. We aim to strengthen our role as a technical advisor to public institutions, ensuring that our scientific and strategic inputs help shape more sustainable and equitable water systems across India.

Impact at scale requires attention to demand-side management, water allocation, and water governance. Photo by Vraj Acharya

5. Water security assessment frameworks must be adaptable to different geographies and stakeholders.

Water security is a multidimensional issue. Its various aspects—water balance, access, productivity, and resilience—are often in competition with each other, making water management a zero-sum game. Thus, an intervention that benefits one stakeholder could be detrimental to another. For example, conserving water in a lake to support migratory birds could come at the cost of nearby farmers, who need the water to irrigate their fields.

The water sector lacks a coherent framework that provides the language and taxonomy to clearly articulate these dimensions. The Water Index for Sustainability, Equity, and Resilience (WISER) may be able to provide such a framework.

However, the framework needs to be adaptable to different contexts as geographical and social conditions vary widely across India. A potential way to achieve this would be to develop two sets of indicators—core and secondary/optional. This approach ensures flexibility, allowing various users to select relevant indicators based on their needs and contexts.

Currently, the collection of primary data under the WISER framework is expensive and time-intensive. With a modular set of indicators, stakeholders can use a mix of primary data and remote sensing that best suits their budgets and needs. Such flexibility can help reduce costs and increase the framework’s uptake across the water sector.

Acknowledgments

Authors Aishwarya Joshi, Ishita Jalan, Karan Misquitta, Utkarsh Upadhyaya, Vanya Mehta, Vivek Singh Grewal

Editor Syed Saad Ahmed

Published by Nanditha Gogate

Follow us to stay updated about our work.