When Wells Fill Fast and Dry Faster: Lessons from Nashik’s Basaltic Uplands

A view of the undulating landscape in Nashik. Photo credit: Vivek Grewal

“Our wells start drying up by February every year” a farmer in Nashik told us. A chorus of “Yes, yes!” quickly followed.

It was mid-monsoon when we visited two villages in Maharashtra’s Nashik district as part of a learning study of the Atal Bhujal Yojana. WELL Labs is conducting the study in collaboration with the Ministry of Jal Shakti, Arghyam, and Water For People. Over 20 farmers from one village joined us at the panchayat office to discuss their challenges with water and its availability throughout the year.

Another farmer chimed in, “Our wells fill up within two months of the start of monsoon. Any rainwater we get after August flows away because the ground underneath is full. But it doesn’t stay that way for long, whether we pump water or not.”

It was a crisp, scientific observation. Aquifers brim quickly and dry quickly—a clear sign of thin basaltic aquifers with limited storage. We heard similar refrains at the second village, which is also located upland of a watershed.

A meeting chaired by the panchayat president and attended by numerous farmers. Photo credit: Karan Mesquitta

Why Do Wells in the Uplands Dry So Soon?

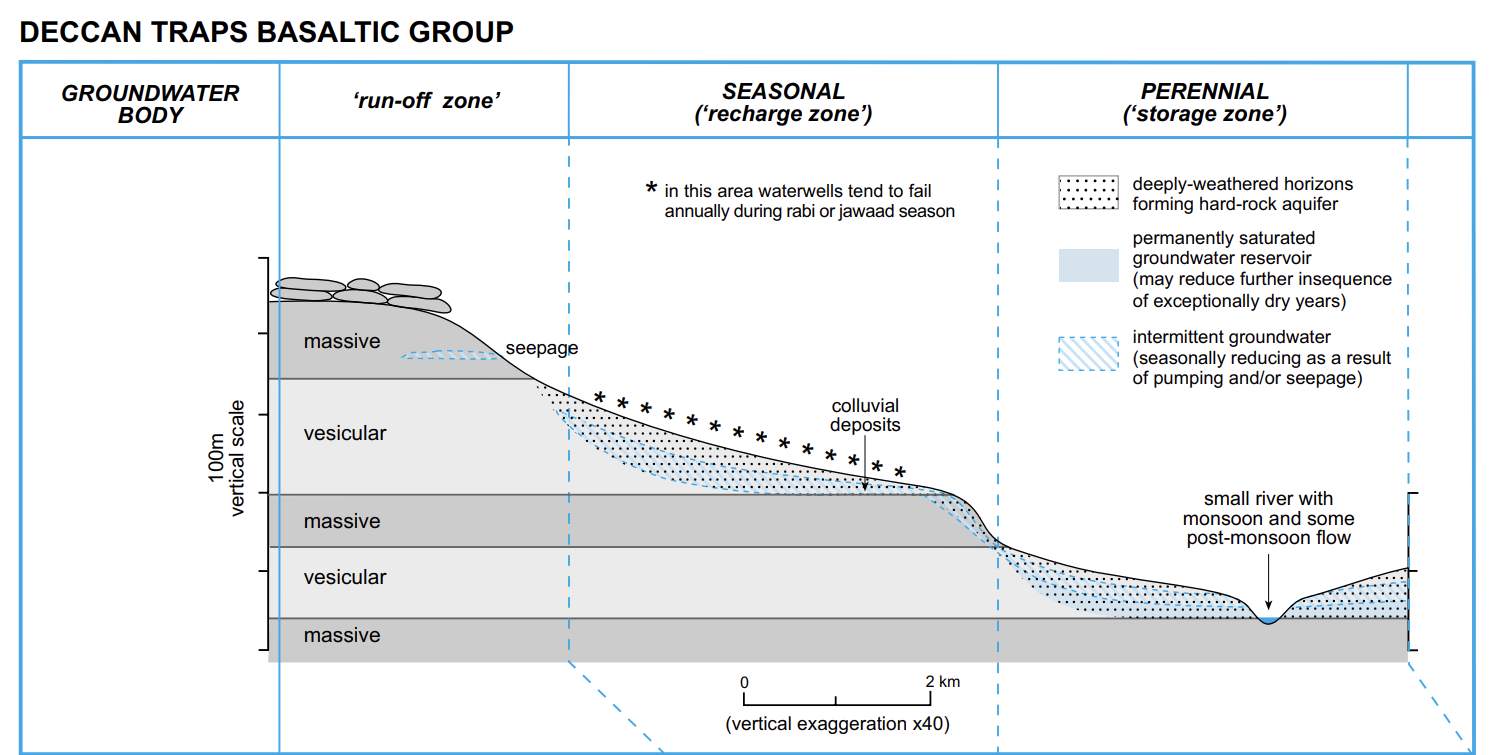

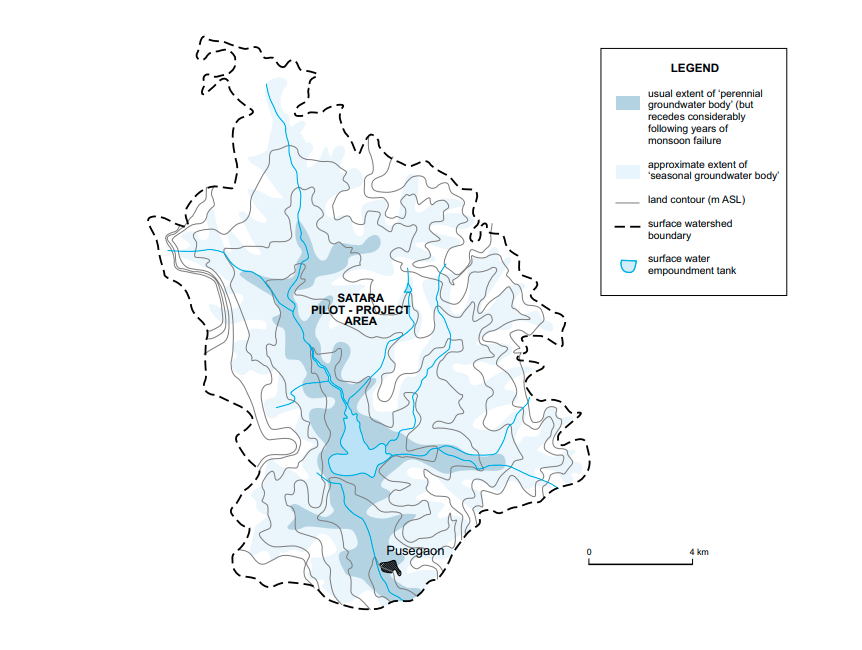

This paradox—plenty of rain, but short-lived groundwater—is common across basaltic uplands of western India. A World Bank report (Foster et al., 2007) describes this well: in such terrains, valleys host ‘perennial groundwater bodies’, while uplands only have ‘seasonal groundwater bodies’. Essentially, much of the water that an upland area receives flows down to the valley after monsoon, creating ‘seasonal’ and ‘perennial’ storage. This is due to a combination of two factors:

- Low-storage aquifers: Unlike large alluvial aquifers in states like Punjab or Assam, basaltic aquifers fill up quickly during monsoon. They are like a sponge—quick to absorb water into its tiny pores and even quicker to release it when squeezed.

- Sharp topography and lateral groundwater flow: Upland villages sit on ridges and slopes. Gravity ensures water flows downhill, both above and below the ground. This lateral sub-surface flow ensures that the uplands dry up and the valleys do not.

Read More | Monitoring and Evaluation of Recharge Pits in Marathwada

A cross-sectional view of the three steps demonstrating how water behaves in uplands and valleys in a basaltic region. Source: World Bank (Foster et al., 2007)

A bird’s-eye view of the three steps demonstrating how water behaves in uplands and valleys in a basaltic region. Source: World Bank (Foster et al., 2007)

Farmers and Agriculture: Coping with Scarcity

Despite the limitations on their aquifers, farmers told us they manage to grow more than before. “Decades ago, we grew just one crop. Now, most of the village grows two crops,” said a farmer.

Through our discussions, we found that this increase in cropping intensity has been possible through:

- Micro-irrigation: Especially drip irrigation, which squeezes the most out of every drop.

- Shifting from wheat to vegetables: Transitioning to crops that have higher value and are less water-intensive.

The view from a hill in Nashik. The seasonal groundwater zone is located in the foreground, and the perennial zone can be seen close to the horizon. Photo credit: Vivek Grewal

To our surprise, the farmers also said that they don’t worry too much about the impact of low rainfall on their rabi (post-monsoon) crops.

“Our aquifers fill up even in years with low rainfall. Most of the rainwater after August flows away, so it doesn’t really matter if it’s a little less overall,” one farmer said. “But the December rain matters as it acts as a top-up to sustain the rabi season.”

This ‘top-up’ in December is crucial as it stretches water availability by a few weeks, long enough to carry a crop to harvest.

Solutions Emerging from the Ground

The valley in the background is where the community wants to build a medium-sized tank. Photo credit: Vaibhav Belhekar

When asked what should be done, the farmers’ answers were clear and pragmatic:

- Surface water storage in uplands: They said that they would prefer surface storage structures rather than recharge structures, like borewell shafts, in the uplands. Since the aquifers fill to the brim with ease in these regions, surface water storage would support the groundwater after monsoon. While this is sound hydrological reasoning and a necessary solution here, if implemented at scale, it would reduce water availability downstream in the valleys—a classic upstream-downstream trade-off.

- Water-use efficiency: The cultivation of remunerative crops, like vegetables, under micro-irrigation was highlighted as a promising path. The major challenges are the risks associated with high-value agriculture, and the knowledge required to do it.

- Water governance: The panchayat leaders said that when wells start to dry up, farmers try to reduce the amount of water they pump for agriculture, to save for domestic use in summers. In rare cases, the panchayat has put out written orders banning excessive irrigation near domestic water wells.

A farmer succinctly summarised the solution for the basaltic uplands: “If we want to grow more crops, we need to build more storage above the ground as the water we receive runs away from us.” All said without technical charts and jargon!

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by Arghyam, Water for People, and Environmental Defense Fund.

Authored by Vivek Grewal

Edited by Ananya Revanna

Follow us and stay updated about our work: